"These are dangerous times more dangerous, I think, than most people seem to imagine. In my opinion, if the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. go on the way they have been going, then we will be lucky to avoid a nuclear war by the end of this century." It was on this serious note that the College began its 215th academic year.

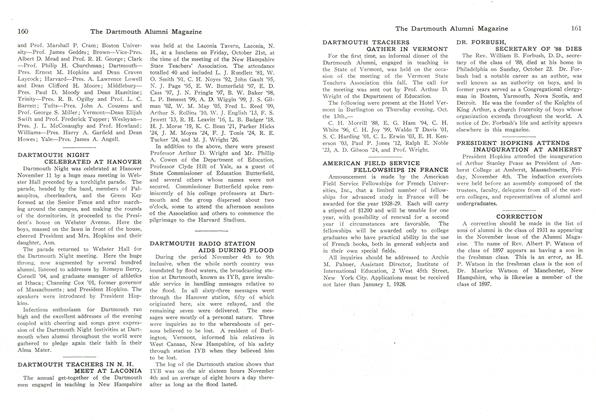

Nobel Laureate Steven Weinberg delivered this message at convocation ceremonies on September 17. It was the second year an outside speaker had addressed convocation at the College, after many years of having only members of the Dartmouth community on the dais. Weinberg, who was on campus to also participate in a celebration of the tenth anniversary of the Fairchild Physical Sciences Center, is the Josey Regental Professor of Science at the University of Texas. He shared the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1979 with two other scientists for work on a theory explaining the relationship between weak nuclear force and electromagnetism.

Weinberg's address,, titled "The Evitability of Technological Change," was received by an audience of about 2,600 students and faculty in Thompson Arena.

Weinberg began by referring to George Orwell's novel 1984, saying, "This is one of those years when we have the chance to check the prophecies in an imaginative work of literature."

Stressing the fact that such novels cannot be perfectly accurate, Weinberg continued, "I am not just making the point that prophecy about technological change is difficult. It is not even easy to see where change should occur at all." But, he went on, "through a vast number of conscious decisions, the costs of particular technological changes outweigh the benefits."

Weinberg went on to cite examples of "conscious technology assessment," such as the supersonic transport (SST) system that the United States decided not to build. "The U.S. was clearly right to reject the SST," he stated. "It is evidently not an easy task to make decisions like the SST decision about the adoption of new technology." Weinberg then explained the catch-22 situation: "Those who know something about the technology in question tend to really be those who had a hand in developing it and are naturally disposed to favor its adoption."

He gave credit for America's sensible decision-making on issues like nuclear power and the SST to the special features of our system of education. "Colleges like Dartmouth, that have been for centuries devoted to the liberal arts, now make a place for science and technology along with the humanities," he said.

Weinberg recalled the mid-19605, when the United States began to develop a multiple independently-targeted reentry vehicle (MIRV) system to penetrate the Soviet Union's "primitive sort of ballistic system around Moscow. The Russians have of course followed us by MlRVing their own missile forces. Because of the incentive to quick action, the decision to deploy MIRV may have been the worst one ever made."

As the address culminated, Weinberg said, "I think the time is long overdue for such a general test ban [of nuclear weapons, their delivery systems, and missile defense and anti-satellite systems] .... If we do not pause right now before testing anti-satellite weapons, it will probably be too late ever to control the destabilizing new technology."

Applause broke out several times during Weinberg's speech.

President of the College David McLaughlin, who had conferred an honorary doctor of science degree upon Weinberg preceding the address, then spoke to the group. McLaughlin set his remarks in the context of the pace of technological change over history, talking about "the heightened role the sciences have, during the past decade, come to play (and increasingly will continue to play) in our lives." He urged educators to resist "the tendency ... to retreat inside departmental and divisional boundaries" and instead to take "a leadership role in achieving, over the next several years, an enhancement of curricular synthesis." He went on to encourage students as well to strive for integration of the sciences and technology within the liberal arts, but he also stressed the need for more than just technological awareness to "utilize positively the potentialities of science productivity." He said students need to develop concern for how their actions affect others, a code of morality and ethics, and a liberal conscience.

Opening remarks for convocation were given by senior class president Elise Miller. A government major from Alexandria, Va., she was the first woman class president to address a Dartmouth convocation. The invocation was delivered by Robert Mac Arthur '64, acting dean of the Tucker Foundation.

"Button, button, who's got the button": Nobel Laureate Steven Weinberg shared a smile with senior class president Elise Miller as he tried to fasten his academic gown before this year's convocation ceremonies. Weinberg was the visiting keynote speaker at convocation, and Miller also addressed the gathering.

The letters home have surely commented, invariably and with emphasis, on how hard the writers are working, on how intensively they are 'booking.' Allowing a little for the hyperbole which is customary in the 'Dear Mom and Dad' form of literature, there is a good deal of truth in the accounts you have received." From his November 1971 letter to freshman parents by Dean Albert I. Dickerson '30

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Draft: To Register or Not to Register

November 1984 By James Heffernan -

Feature

FeatureLife After the Presidency

November 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

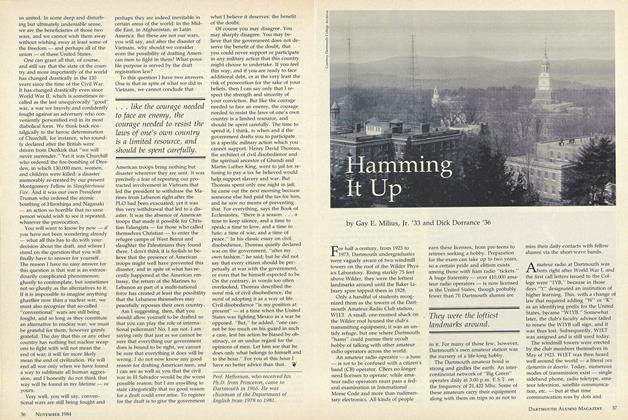

FeatureHamming It Up

November 1984 By Gay E. Milius, Jr. '33 and Dick Dorrance '36 -

Feature

FeatureGet a Job

November 1984 By Nancy Wasserman '77 -

Feature

FeaturePractice, practice, practice

November 1984 -

Books

BooksSo Much More

November 1984 By Peter Smith