In his account of the story of Dartmouth past and present, The College On the Hill, Ralph Nading Hill refers to the "Dartmouth Spirit" as "the impelling element in the Dartmouth organism," and suggests that in order to begin to understand Dartmouth, one must first recognize and appreciate that intangible yet ever vital spirit. The rich and colorful history of Dartmouth Hall, which celebrates its bicentennial this year, incorporates much of the es- sence of that spirit. As Henry Freder- ick Lenning '37 noted in his senior thesis on the history of Dartmouth Hall, the building is "not just a pile of brick and wood" but rather "a living and vibrant organism that is the heart of a great institution." He asserted moreover that the history of Dartmouth Hall could be read as a kind of "barometer for the history of Dartmouth College," one which "has al ways reflected the years and events as has no other monument on our campus."

The story of Dartmouth Hall from its beginnings to its two-hundred year evolvement through three structural incarnations is infused with the high drama of physical catastrophe (including three major fires and a tornado) as well as with the low comedy of student pranks and occasional faculty eccentricities. Throughout its often tumultuous, uncertain history, however, Dartmouth Hall would always be recognized as the architectural, social, and spiritual hub of the College.

As early as 1774, the College's need for a central, well-constructed (and thus permanent) building had become obvious. In addition to Eleazar Wheelock's manse, the entire College plant at that time consisted of only three buildings, all built on the meagerest of clay foundations. These were a log hut, Old College, and Old College Hall, which, during a so called "nocturnal visitation" in 1789, was demolished by disgruntled students who had become impatient with the delapidated condition of the former hall and meeting room. Wheelock's somewhat ambitious plan for a new permanent structure, as outlined in a letter of 1770 to the English Trust, was to build a hall "with brick, 200'x50',3 stories high." In that same letter, he requested glass, paint, nails, locks, hinges, and other building materials. Upon the discovery of stone about three quarters of a mile from the proposed site, however, Wheelock seemed attracted to the more practical plan of using stone at least for the cellar and ground story.

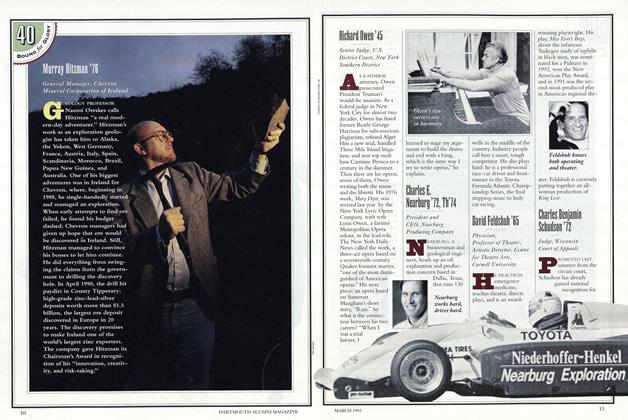

By the time a definite plan for the building emerged sometime between 1771 and 1773, however, Wheelock had expediently proposed "to finish it in the most plain, decent, and cheapest manner, after the Dorrick Order." Plans were commissioned from two artists: Peter Harrison (noted designer of the British Market in Newport, Kings Chapel in Boston, and Christ Church in Cambridge), and the lesserknown William Gamble. Although Harrison's plan (which was accepted by the College) has since disappeared, Dartmouth is still in possession of Gamble's rejected plan, which bears a striking resemblance to Dartmouth Hall as finally constructed a decade later, leading some architectural historians to speculate that an unknown designer worked with a composite of both plans.

Despite the much scaled down plan for the project, it unfortunately fell victim to the scarcity of funds and the general turmoil caused by the Revolution; for the next ten years, all attempts to raise funds for the building failed. Although Wheelock managed to have a cellar excavated near the site of the present building, he died before his dream of a stately college hall was fulfilled.

By 1784 the original buildings of the College were in a state of almost complete ruin, such that the fate of the College was called into question. On March 31 of that year, a meeting of the Trustees was called to discuss thefutureof he ollege. The Trustees officially agreed to the erection of a central building long enough for six comfortable rooms on each side, with two studies in each room, two entries wide, and three to four stories high. The Board also selected the site formerly proposed by Wheelock, "a rise on the East side of the green," stipulating that construction was to commence as soos£2000d been raised by subscription. Although £3OOO, payable in "lawful money, beef, pork, grain, or boards. . .or glass, nails or merchandise at the value thereof" had been pledged, the Board revised its plan and decided to use wood instead of brick for the major portion of the building, having learned from earlier experiences the discrepancy between monies pledged and funds actually collected.

On November 3, 1784, the New Hampshire Legislature authorized a public lottery, but the tickets sold so slowly that not even prize money could be collected. Three years later, the legislature authorized a renewal of the lottery which, after the expenses of the first disastrous lottery were paid, yielded a meagre £366. Another £4OO was borrowed, the final installment of which was finally paid back after the turn of the century.

In 1784, the cellar for the building was finally dug and the stone foundation laid. Wages to laborers helping with the project were paid in gifts of beef, hide, clothing, and, quite often, rum. (An early expense record indicates that on September 29, 1784, one Mr. Holden received two quarts of rum in return for his work digging the cellar.) Lenning notes that the spirits of many of the workmen were "refreshed by prayer" and their bodies "refreshed by spirits." Work progressed continuously, if somewhat slowly, and by 1788, the building was sufficiently completed to accommodate the Commencement exercises of 1787 on the lower floor. Unfortunately, a platform erected in the center for the occasion collapsed during the ceremonies, so that "some of the reverend gentlemen had to look for themselves in one place and for their wigs in another."

Financial problems continued to impede the construction of the building, but in 1792 the hall was finally completed. The precise cost of the hall is difficult to calculate from the scant and confusing records that still exist, but it has been estimated in the neighborhood of £4500.

Dartmouth Hall, known simply as "The College" until 1828 (when Thornton and Wentworth Halls were erected), remained the educational center of the College until 1904. It housed the library and a museum "of curiosities collected by former graduates and others on their travels," among whose treasures was a stuffed zebra which the students delighted in removing and transporting to the belfry or the stage of the College chapel. But most of the rooms served as dormitories, which were, for the most part, bare and uncomfortable.

In early March 1798, the hall narrowly escaped disaster when a fire broke out in a room in the northwest corner of the second story. Fortunately, it was quickly contained, and damage was limited to about $100. A tornado in June 1802 struck Hanover with such velocity that it unroofed the south end of the building. But as Francis Lane Childs '06 noted in a 1936 Alumni Magazine article, "As destructive agents, fire and tornado were little worse than the undergraduates of the early 1800s. In the frequent riotous encounters between the students and the villagers . . . stones and brickbats flew back and forth with calamitous results, and when disagreements arose as they often did between the students and the faculty, muskets were sometimes discharged through the windows of the tutors' rooms." At one point the young men, after being locked out of Dartmouth Hall for some unknown offense, obtained an old cannon, loaded it with powder, and blew down the obstruction. The students were fined $4OO for damage to the building and for violating College rules. In 1810 there occurred the culmination of what might be called "The Great Cow War." It seems that villagers had taken to leaving their cows on the common at night, which the students found to be such a continuing nuisance that on the night of June 19, a group of about 60 students drove some 20 cows into the cellar of the hall and blocked the entrance with boulders. By eleven the next morning, a confrontation between the students (who had locked themselves in the hall performing one of the country's first college "sit ins") and a group of armed cow owners threatened to erupt into violence. The distraught faculty alternately commanded and pleaded with the students to release the cows, to no avail. Finally Professor Hubbard knocked out the panels of a door with an ax, allowing the faculty to take possession of the building. The villagers were told to dig their cattle out, and students were fined $25 each for damages to the cattle and the building.

In 1817, the building survived yet another student riot, this one a confrontation between the University and College factions in the Dartmouth College Case. When the University attempted to seize possession of the private libraries of the Socials and Fraters (the two literary societies) housed in the hall, students armed with wooden billets stood outside the door screaming, "No one shall bring out a book alive," and the raiders were forced to leave the premises.

In 1828, a large room to be used as a chapel was constructed in the center of the building, two stories high, with a balcony running along the second level, and an organ and a choir on the west side. The Dartmouth Hall Chapel was the center of student life until the completion of Rollins Chapel in 1885, and as well the scene of innumerable student pranks. As Childs related, "The President never knew when he entered the room what sight would greet his eyes," for students might bring in anything from a flock of turkeys to a corpse stolen from the Medical School. The most celebrated of these escapades elicited the now classic repartee from President Bartlett, who, upon seeing a small donkey tied to a desk on the stage, calmly said to the assembled students, "Excuse me, gentlemen. I did not know you were holding a class meeting," after which he quietly left the Hall.

Shortly before 8 O'clock on the bitter cold morning of February 18, 1904, Prof. Childs recalled, a fire broke out in the front center of Dartmouth Hall. Just ten minutes earlier, the entire student body had left their dormitory rooms on the third floor of Dartmouth to attend morning prayers in Rollins Chapel. Hearing cries of alarm outside and ascertaining their import, President Tucker tersely announced, "Dartmouth Hall is on fire," and chapel was abruptly dismissed. The Hanover Village fire crew, aided by students, faculty members, and other townspeople, stretched hose lines from Fayerweather Hall in a valiant but futile effort to subdue the blaze: the 20° below zero temperature turned the water into sheets of ice even as it streamed onto the fiercely burning pine and oak timbers of the century old structure. In less than two hours, the building that had come to be known as "Bedbug Alley" was completely gutted by fire. Ralph Nading Hill wrote:

Shocked spectators remembered a fewmoments when, after all except a chimney and a fragment of wall had beenconsumed, the massive hand hewn timbers of the frame, outlined by fire, stillstood, the last reminder of the energiesof the early College. Every spectator,recalled Professor Eric Kelly, shared afeeling that somehow or other the worldhad come to an end. Only the night before, as on countless occasions beyondmemory, Dartmouth Hall had been thescene of a mass meeting. Suddenly allthe jokes about "Bedbug Alley" on thethird floor no longer seemed funny.When he read of the blackened ruinthere was not an alumnus from whosememory a hundred nostalgic images didnot spring.

The spirit of Dartmouth Hall survived the great fire of 1904, and in fact College historians agree that the event, disastrous as it was, marked a major turning point in the history of the College itself. Even before the last flames of the fire were doused, President Tucker assembled the Board of Trustees to consider plans for rebuilding Dartmouth Hall. Melvin O. Adams '71 concurrently issued what has become the most famous call for help to Dartmouth alumni in the annals of the College: ""This is not an invitation; it is a summons." As Professor Childs noted, "More than any other single event, [the disaster] served to crystallize alumni sentiment, and the immediate and generous response in money given at the time marked the beginning of that never failing support of their alma mater that has characterized the alumni body ever since."

It was decided to rebuild the hall on the same site and along the same lines, based on plans drawn up by architect Charles A. Rich '75, using red brick painted white instead of wood. Due to the vigorous fundraising efforts among the alumni, the rebuilding proceeded smoothly, and the cornerstone of the new hall was laid on October 26,1904, by the Sixth Earl of Dartmouth, great great grandson of the Second Earl, for whom the College is named. The new building was dedicated in the uncomfortable (it was freezing outside), but nonetheless jubilant atmosphere of February 17, 1906.

Outwardly the building appeared much the same as the old hall (the white painted brick simulated the white wooden structure), but in place of the two-story chapel, Childs noted in the Jan. 1936 Magazine, was a lecture room. The new hall housed the departments of English, French, Ger- man, Greek, Latin, philosophy, psychology, art and archaeology, many of which overflowed into other buildings as the College grew.

For 30 years the second incarnation of Dartmouth Hall remained essentially unchanged. Then, at 1:20 a.m. on the morning of April 25, 1935, a fire that started in the basement of the north wing spread rapidly throughout the building until the entire structure was gutted, leaving only the outside brick walls. Even the cupola and roof were destroyed before the Hanover and Lebanon volunteer fire departments were able to quell the flames. Undaunted, the Trustees voted at their May meeting to rebuild the hall, using the brick walls left standing after the blaze. It was decided to construct an entirely new fireproof interior of steel and concrete, and after plans were drawn up by Jens Fredrick Larson, College architect, construction on the third incarnation of Dartmouth Hall by W.H. Trumbull of Hanover proceeded rapidly. Once again, the exterior of the new Hall remained unchanged; the bell presented in 1904 by J.W. Pierce hung and set to be struck electronically in connection with the chime system in Baker Tower. The major interior change, according to Childs, was the reconstruction of the pre 1904 twostory chapel in the form of a central auditorium, dropped down to the basement and ground floor levels.

Over the years, Dartmouth Hall has been the object of much aesthetic and architectural criticism: students during the 1840s commonly referred to it as "the old barn" or "Noah's Ark," and at one point President Tucker aptly called it a "tinder box." Whether dictated by sentiment or aesthetic taste, however, it is now generally agreed that its lack of architectural pretense makes Dartmouth Hall one of the most aesthetically pleasing buildings on the College campus. Professor Childs' assessment of the newly-reconstructed Dartmouth Hall in 1936 applies equally to Dartmouth Hall as it celebrates its 200 th Anniversary: "Dartmouth Hall has dominated the campus of Dartmouth College, and it still does. . . . To the men of Webster's generation it was the sole physical embodiment of the small College that they loved; to the present undergraduate its gleaming walls are yet the chief visible symbol of 'Dartmouth Undying.' "

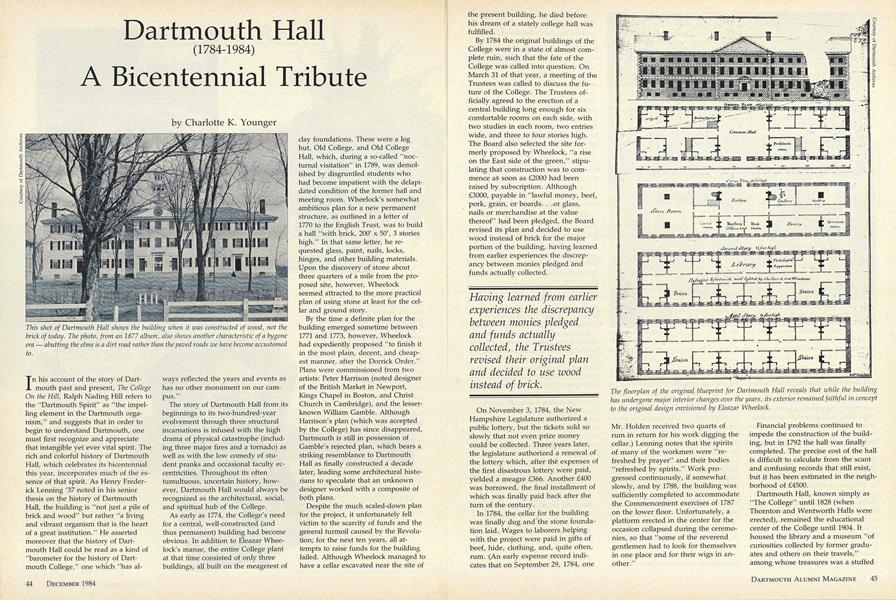

This shot of Dartmouth Hall shows the building when it was constructed of wood, not thebrick of today. The photo, from an 1877 album, also shows another characteristic of a bygoneera abutting the elms is a dirt road rather than the paved roads we have become accustomedto.

The floorplan of the original, blueprint for Dartmouth Hall reveals that while the buildinghas undergone major interior changes over the years, its exterior remained faithful in conceptto the original design envisioned by Eleazar Wheelock.

One of the most dramatic photos of the 1904 fire the "great fire" made the papersthroughout the Northeast. The conflagration, of unknown origin, brought to Dartmouthalumni a very famous plea for financial assistance: "This is not an invitation; it is asummons."

The 1935 fire led the Trustees to insist on a fireproof interior of steel and concrete to preventfurther such disasters. The exterior, as usual, remained virtually unchanged a buildingmore than "just a pile of brick and wood the heart of a great institution."

Having learned from earlierexperiences the discrepancybetween monies pledgedand funds actuallycollected, the Trusteesrevised their original planand decided to use woodinstead of brick.

The chapel in Dartmouth Hall was the scene of manyescapades, the most celebrated involving PresidentBartlett, who walked in to find a donkey tied to a desk onstage. "Excuse me, gentlemen," he quipped. "I did notknow you were holding a class meeting."

Charlotte K. Younger is a freelance writerliving in Thetford Center, Vt. Some of thematerial in this article is drawn from thelate Francis Lane Childs 'o6's piece in the Alumni Magazine in January 1936.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

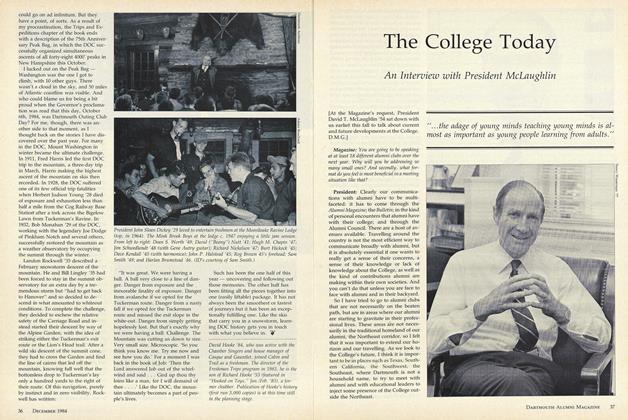

FeatureThe College Today

December 1984 -

Feature

FeatureChronicling the DOC

December 1984 By David O. Hooke '84 -

Feature

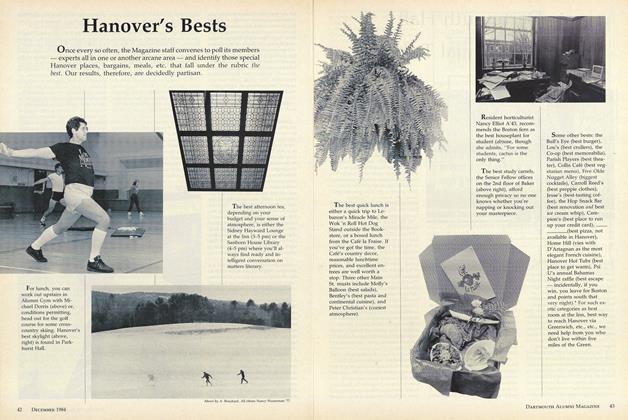

FeatureHanover's Bests

December 1984 -

Article

ArticleLover of parades

December 1984 By Peggy Sadler -

Class Notes

Class Notes1940

December 1984 By Richard J. Goulder -

Sports

SportsHonors for harriers

December 1984 By Jim Kenyon