A noble experiment which continues to this day

The Artists in Residence program at Dartmouth has a fascinating history, one that began more than fifty years ago with the planning and completion of Carpenter Hall, the College's first building devoted entirely to the visual arts.

Opened in 1929, this new building housed a revitalized Department of Art authorized by the faculty of the College to teach a full major program in Art History and with a mandate from President Hopkins to make the visual arts a more central and vital part of the Dartmouth educational experience. The instructional spaces in the building were ideal; every instructor s office had a connecting seminar room; the lecture halls were of three sizes to accommodate classes of 35, 80, or 150 students; there were expandable spaces for a firstclass art library and collection; a spacious series of seven art exhibition galleries had work and storage areas to service them. Additionally, and more radically, there were art-studio spaces; a large studio for student activity in drawing, painting, sculpting, or print making; and a smaller private studio for a visiting artist who might be a role-model and, if he wished, act as a coach for the students.

It is worth remembering that in 1929 studio activities had no academic standing and could not receive any academic credit. Such activities had to be strictly extra-curricular, since the majority of the College faculty considered them as forms of play, like athletics, acting or making musical sounds. Dartmouth students, however, responded immediately and enthusiastically to this new extra-curricular opportunity for creative activity in art.

These students turned, naturally, to the Art Department for guidance and support in the kind of activity that each wished to explore. The teachers volunteered their help but it was obvious that the background and training of an art historian was inadequate for serious coaching in the studio. We took the problem to President Hopkins and he was, as usual, understanding and helpful. He agreed that there was educational value in providing firsthand contact with a serious working artist and that, if we could find one willing to experiment with us in the Carpenter Studios, he would tap a discretionary tutorial fund recently given to the College by Mr. and Mrs. John D. Rockefeller, Jr., whose son, Nelson Aldrich Rockefeller, had just won a Senior Fellowship and had elected to spend his entire senior year (1929-1930) studying art history in Carpenter Hall.

We found just the right man in Carlos Sanchez, a Dartmouth graduate of the Class of 1923 with an advanced degree in architecture from Yale and considerable success as a rising young painter, both in the United States and in his native Guatemala. Sanchez became our first "Fellow in Art," agreeing to practice his own professional craft in the Carpenter Studios and also make himself available to our students who might wish encouragement and support in their own artistic endeavors. He was willing to coach the students either individually or in small classes in experimental ways that were neither academic in the traditional sense nor vocational in the manner of the professional art school.

Mr. Sanchez was successful well beyond our expectations. One student, Wilbur H. Ferry, Class of 1932, writing in Decem- ber, 1931, for the Undergraduate Chair column of the ALUMNI MAGAZINE said: Mr. Carlos Sanchez has come to the College as an instructor and general helper in all branches of pictorial and plastic art. He has had a most enthu- siastic reception, and classes, held daily, please us by growing and growing. A well equipped studio on the top floor of Carpenter has been given over, and all facilities are of the finest. This, if the same enthusiasm continues, will undoubtedly be given a standard place in the college cur- riculum for it tends more to one of the ends of a liberal college than anything else we know of.

When Sanchez left Dartmouth in 1933 to return to Guatamala he wrote to Presi- dent Hopkins as follows: The opportunity I was given when invited up to Dartmouth was one for which I shall be always grateful . . . an experiment that according to the general opinion at Hanover was not unsuccessful, and I, for my part, feel that the contact with faculty and stu- dents was to me. rich in spiritual worth, and I want to thank both the College for the encouragement and the students for their cooperation in the double experiment.

The stay of Carlos Sanchez at Dartmouth (1931—1933) overlapped the 1932-1934 residency of Jose Clemente Orozco; and student enthusiasm for Mr. Sanchez passed directly and most warmly to Sr. Orozco. Upon completion of the great Baker Library murals, it was the student organization, "The Arts," that gave the artist a banquet in the Hanover Inn and presented him with a gold watch inscribed as a token of their esteem.

Orozco came to Dartmouth first in the spring of 1932 for a two-week lecture- demonstration of the art of mural painting in fresco. In June of the same year he returned for his appointment as Assistant Professor of Art with the assignment of practicing his special craft of fresco mural painting in the Reserve Book Hall of Baker Library. This two-year stay on campus of a major Artist in Residence was a tremendous educational experience, not only for the art students, but for the entire student body and also for both the faculty and the whole College community. The public nature of the project, its grand scale and the boldness of its intellectual and emotional content received world-wide publicity. The College was buffeted by waves of praise and high acclaim on the one hand, and pounded with condemnation and snide misunderstanding on the other. In all the excitement there was danger of overlooking the great success of our intent: namely, to offer our students the opportunity to know a mature, serious artist and to observe him at work as a normal, even though somewhat specialized, producer in a civilized society.

During the entire decade of the 1930s We were experimenting with the artist-in-residence idea ail kinds of artists from ultra-conservative to avant-garde; all types of artistic personality; all sorts of media and craft. The only artists we tried to avoid were the jokers, the fakers, and the band-wagon riders, the ones without personal integrity.

In our experience with serious artists, we found that many would come to Hanover for short visits, but very few would leave their home bases for an extended stay. We had, therefore, a long string of architects, artists, and craftsmen who came for a few days or, at most, a few weeks. Among this group I recall Alvar Aalto, Josef Albers, Thomas Hart Benton, Stuart Davis, Buckminster Fuller, Walter Gropius, George Howe, Reginald Marsh, Lewis Mumford, Elliot O'Hara, Charles Woodbury, and Mahonri Young.

For longer stays, measured in years rather than days, we had Adelbert Ames (artist and scientist), Curt Behrendt (city planner), Lawren Harris (painter), Jens Fredrick Larson (architect), Ray Nash (printer and graphic designer), Virgil Poling (craftsman), Sanford Ross (painter), Paul Sample (painter) and Carl Schaeffer (painter). Messers. Behrendt, Larson, Nash, and Sample received academic appointments and had faculty status as teachers.

In the late 1930s when Paul Sample, Class of 1920, a distinguished American artist whose paintings were in the collections of many major museums, was given a lifetime appointment as Artist in Residence with the rank of full professor, the long-held barriers to academic credit for work in the art studios began to crumble. Art majors who had demonstrated special talent in drawing and painting were permitted to receive course credit as "Honors Work" under the professional guidance of Mr. Sample. Exhibitions of such work were convincing proof of the quality and integrity of both the teaching and the learning activity.

For several years during and shortly after World War 11, 1941-1946, Dartmouth was primarily a training institution for U.S. Navy and Marine officers and cadets. There were still a few civilians at the College and instruction in art did not entirely cease, but the Art Faculty put its major time and effort into teaching naval history, military map making, or physics. (Indeed, this author is a scarred survivor of instructional battles with physics.)

After the war, the arts at Dartmouth were soon flourishing again. Enrollment in art history courses reached record levels and activities in the Art Studio were booming. We had to expand the studio space into the former Clark School gymnasium which is now Fairbanks Hall (named for Professor Arthur Fairbanks who was chairman of the Art Department at the time Carpenter Hall was planned). The pressure of this post-war boom in the visual arts resulted in more art faculty and a wider range of art courses, including, at last, a large group of studio courses with academic credit. The teaching artists in the late 1940s and 1950s were Winslow Eaves, Peter Michael Gish, Edgar H. Hunter, Jr., Charles Morey, Ray Nash, Virgil Poling, Paul Sample, and Richard Wagner.

We also continued, of course, the briefer visits of role-model Visiting Artists. In fact there were a great many of them. Among those I personally remember were Ivan Albright, Leonard Baskin, Russell Cowles, Stuart Eldredge, David Fredenthal, Thomas George, Wallace Harrison, Un-Ichi Hiratsuka, Hans Hofmann, Will Hollingsworth, Rockwell Kent, Irving Marantz, Shiko Munakata, Alice Neal, Pier Luigi Nervi, Abraham Rattner, Ben Shahn, John Sloan, Byron Thomas, George Tooker, Warren Wheelock, and Eugene Witten.

The expansionist pressures in the visual arts were also being felt in the dramatic and musical arts and it was the evergrowing student demands that made clear the need for something much greater than patchwork remedies. It was this realization that brought the Trustees to authorize the planning of a major art center for Dart- mouth. Most fortunately, an ideal central site was available at the south-east corner of the green and, obviously here was the opportunity to honor the man who had done so much to add vitality to Dartmouth through the arts, President Emeritus Ernest Martin Hopkins. By applying his name to the concept of bringing all the arts together under one expansive roof, and doing so at a time when he could fully enjoy the planning, the elaborate construction, and the very happy completion, the Trustees were honoring President Hopkins in a most delightful way. It could also be said that they were honoring the entire Dartmouth Family which had so loyally followed Hoppy's leadership.

President Hopkins's successor, John Sloan Dickey, masterminded the planning and construction of the Hopkins Center. His creative vision, his energy, and his optimism guided the Building Committee around many dangerous corners., just as his powers of persuasion and steadfastness of purpose overcame the doubts and fears of nay-sayers among the Alumni. In a very real sense, John Dickey was both the Producer and the Director of the dramatic hit, "The Hopkins Center."

With the completion of the Hopkins Center in 1962 we had, among many other good things, a fine series of art studio facilities and the opportunity for a first-class visual-studies program. We also had a special studio for an Artist in Residence and the chance to adapt its use to the four-term plan that was being proposed for Dartmouth. We adopted a standard plan of having one carefully chosen Artist in Residence at work in the Hopkins Center studio during each term. It turned out, quite happily, that the ten-week Dartmouth term was just right for the artists. The period was long enough for them to have a real change of pace in a new and pleasant environment, and not too long for them to be away from their professional sources and the art marketplaces.

Our students, too, found the ten-week term an adequate period for getting to know an artist. There was enough time to observe him or her at the daily routine of work and there could be many opportunities to speak with the artist, both formally in the classroom, studio, or gallery, and informally in the snack-bar, movie theater, or almost anywhere on campus.

For a few very lucky and talented students there has been experience similar to the Renaissance tradition of apprenticeship with a master in the master's atelier. A great many students have expressed enthusiasm and satisfaction with the Artists in Residence program as a meaningful and rewarding, even though unstructured, part of their art education.

The Hopkins Center is now 21 years old and an impressive number of artists have been resident here during that time. I shall list only the names that I recall from the first half of this time period, knowing very well that Professor Matthew Wysocki, the current Director of Visual Studies, could add an equally impressive list, both in number and quality, of recent residents:

Richard Anuszkiewicz, Hannes Beckmann, Max Berndt-Cohen, Varujan Boghosian, Judith Brown, William Christopher, Friedl Dzubas, Xavier Esqueda, Sorel Etrog, Yu Fujiwara, Paul Georges, Dimitri Hadzi, Joseph Hirsch, Jaques Hurtibise, Thomas Huxley-Jones, Donald Judd, Lyman Kipp, Nicholas Krushenick, Leroy Lamis, Walter Murch, Robert Rauschenberg, George Rickey, James Rosati, Jason Seley, Julian Stanczak, Frank Stella, Tal Streeter, Elbert Weinberg, Jack Zajac, Richard Zieman, and Larry Zox.

In short, Dartmouth was a pioneer in the practice called "Artists in Residence." The College's Department of Art developed this practice as a worthy supplement to the conventional structured teaching of the visual arts. This educational enrichment of basic academic instruction has been enjoyed by the College for more than 50 years. There have been approximately 200 Artists in Residence at Dartmouth and perhaps they were a sort of ghost or spirit faculty. They might be considered once-and-future Emeriti. They might also be thought of as unofficial Alumni. Since a great many of them have expressed their respect, affection and loyalty for Dartmouth, I believe that, no matter how brief their residency, they did gain some measure of that deep and mysterious love for the College that so distinguishes all other groups of the Dartmouth Family.

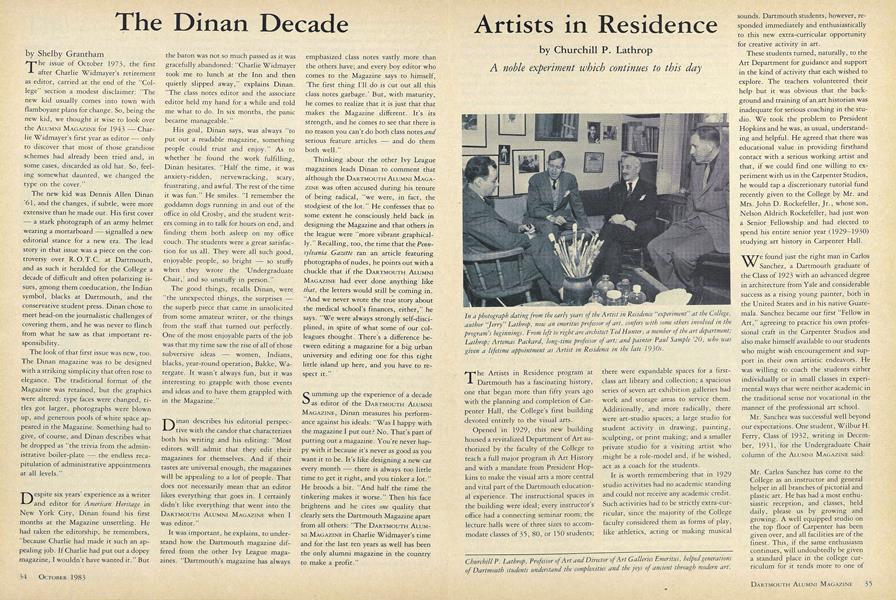

In a photograph dating from the early years of the Artist in Residence "experiment at the College,author "Jerry' Lathrop, now an emeritus professor of art, confers with some others involved in theprogram's beginnings. From left to right are architect Ted Hunter, a member of the art department;Lathrop; Artemas Packard, long-time professor of art; and painter Paul Sample 20, who wasgiven a lifetime appointment as Artist in Residence in the late 19305.

Ceramist Yu Fujiwara,, right, a Japanese national treasure, works here with one of the countlessstudents who have benefited over the years from the presence on campus of the painters, sculptors,architects, and craftsmen whom the Artist in Residence program has brought to Hanover. Theinhabitants of the visiting artist's studio have both shared their expertise with undergraduates andbeen willing to be observed while they were themselves involved in the creative process.

Churchill?. Lathrop, Professor of Art and Director of Art Galleries Emeritus, helped generationsof Dartmouth students understand the complexities and the joys of ancient through modern art.

President Hopkins agreed thatthere was educational value inproviding firsthand contact witha serious working artist.

This two-year stay on campus of amajor Artist in Residence was atremendous educational experience, not only for the art studentsbut for ... the whole Collegecommunity.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDoubt and Passion: Notes on Contemporary American Novelists

October 1983 By Horace Porter -

Feature

Feature40 Years at the Helm

October 1983 By Charlie Widmayer '30 -

Feature

FeatureRudolph Ruzicka's Two Dartmouth Medals

October 1983 By Edward Connery Lathem -

Feature

FeatureMeet Ted Leland

October 1983 By Brad Hills '65 -

Feature

FeatureThe Widmayer Touch

October 1983 By Cliff Jordan '45 -

Feature

FeatureLessons from the Past

October 1983 By Allen A. Ryan '66

Churchill P. Lathrop

-

Books

BooksIT'S A LONG WAY TO HEAVEN

February 1946 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Books

BooksMEDIEVAL MENAGERIE

March 1953 By Churchill P. Lathrop -

Books

BooksCAVE DRAWINGS FOR THE FUTURE.

June 1954 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

FeatureHopkins Center and Dartmouth Hall

July 1957 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Books

BooksART AS AN INVESTMENT.

January 1962 By CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

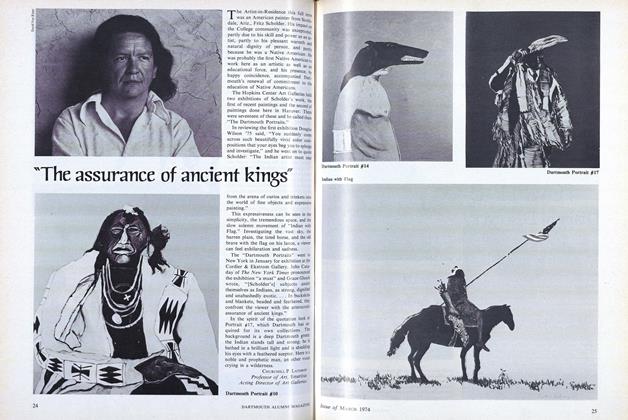

Feature"The assurance of ancient kings"

March 1974 By Churchill P. Lathrop

Features

-

Feature

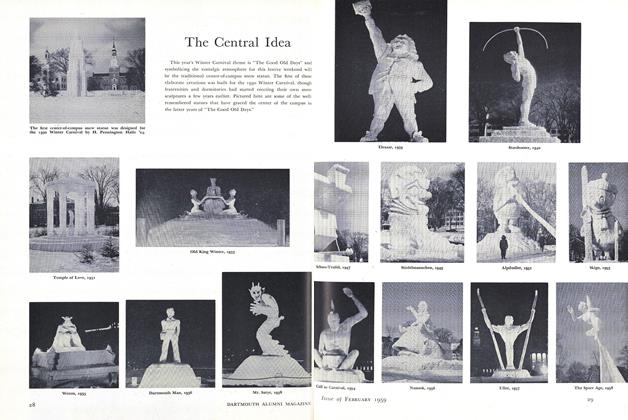

FeatureThe Central Idea

FEBRUARY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureRobert Huke Professor of Geography 150 catfish in a single dame

January 1975 -

Feature

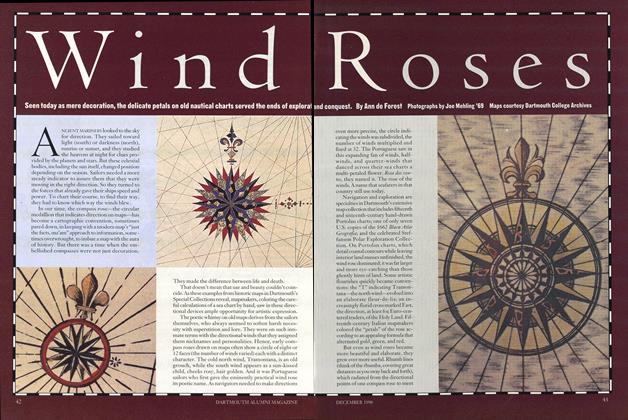

FeatureWind Roses

DECEMBER 1998 By Ann de Forest -

Feature

FeatureThe Poetry of History: William Faulkner's Image of the South

May 1960 By HENRY L. TERRIE JR. -

Feature

FeatureBob Graham '40, Newsman

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Howard Coffin -

Feature

FeatureLast Person Rural

June 1992 By Noel Perrin