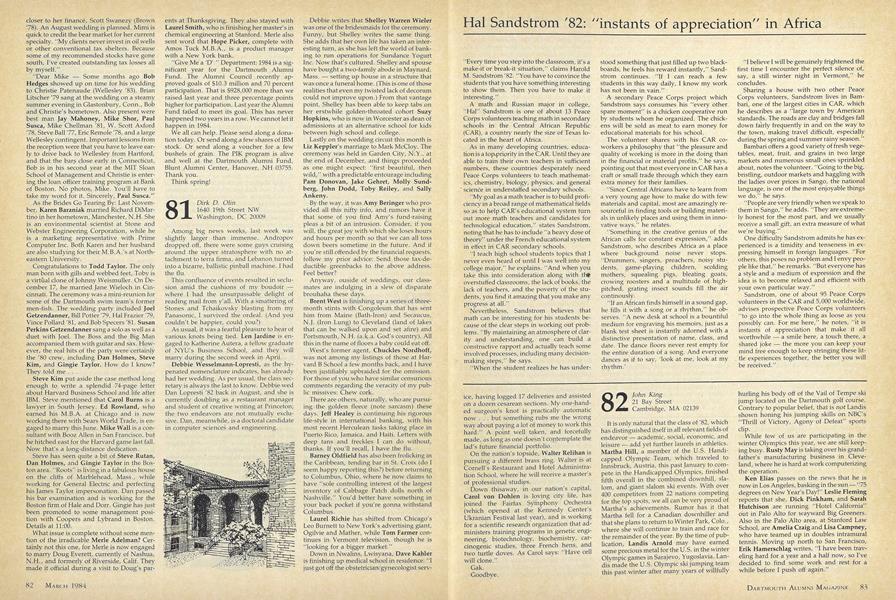

"Every time you step into the classroom, it's a make-it or break-it situation," claims Harold M. Sandstrom '82. "You have to convince the students that you have something interesting to show them. Then you have to make it interesting."

A math and Russian major in college, "Hal" Sandstrom is one of about 13 Peace Corps volunteers teaching math in secondary schools in the Central African Republic (CAR), a country nearly the size of Texas located in the heart of Africa.

As in many developing countries, education is a top-priority in the CAR. Until they are able to train their own teachers in sufficient numbers, these countries desperately need Peace Corps volunteers to teach mathematics, chemistry, biology, physics, and general science in understaffed secondary schools.

"My goal as a math teacher is to build proficiency in a broad range of mathematical fields so as to help CAR's educational system turn out more math teachers and candidates for technological education," states Sandstrom, noting that he has to include "a heavy dose of theory" under the French educational system in effect in CAR secondary schools.

"I teach high school students topics that I never even heard of until I was well into my college major," he explains. "And when you take this into consideration along with the overstuffed classrooms, the lack of books, the lack of teachers, and the poverty of the students, you find it amazing that you make any progress at all."

Nevertheless, Sandstrom believes that math can be interesting for his students because of the clear steps in working out problems. "By maintaining an atmosphere of clarity and understanding, ' one can build a constructive rapport and actually teach some involved processes, including many decisionmaking steps," he says.

"When the student realizes he has understood something that just filled up two blackboards, he feels his reward instantly," Sandstrom continues. "If I can reach a few students in this way daily, I know my work has not been in vain."

A secondary Peace Corps project which Sandstrom says consumes his "every other spare moment" is a chicken cooperative run by students whom he organized. The chickens will be sold as meat to earn money for educational materials for his school. The volunteer shares with his CAR coworkers a philosophy that "the pleasure and quality of working is more in the doing than in the financial or material profits," he says, pointing out that most everyone in CAR has a craft or small trade through which they earn extra money for their families.

"Since Central Africans have to learn from a very young age how to make do with few materials and capital, most are amazingly resourceful in finding tools or building materials in unlikely places and using them in innovative ways," he relates.

"Something in the creative genius of the African calls for constant expression," adds Sandstrom, who describes Africa as a place where background noise never stops. "Drummers, singers, preachers, noisy students, game-playing children, scolding mothers, squealing pigs, bleating goats, crowing roosters and a multitude of highpitched, grating insect sounds fill the air continously.

"If an African finds himself in a sound gap, he fills it with a song or a rhythm," he observes. "A new desk at school is a bountiful medium for engraving his memoirs, just as a blank test sheet is instantly adorned with a distinctive presentation of name, class, and date. The dance floors never rest empty for the entire duration of a song. And everyone dances as if to say, 'look at me, look at my rhythm.'

"I believe I will be genuinely frightened the first time I encounter the perfect silence of, say, a still winter night in Vermont," he concludes.

Sharing a house with two other Peace Corps volunteers, Sandstrom lives in Banv bari, one of the largest cities in CAR, which he describes as a "large town by American standards. The roads are clay and bridges fall down fairly frequently in and on the way to the town, making travel difficult, especially during the spring and summer rainy season."

Bambari offers a good variety of fresh vegetables, meat, fruit, and grains in two large markets and numerous small ones sprinkled about, notes the volunteer. "Going to the big, bristling, outdoor markets and haggling with the ladies over prices in Sango, the national language, is one of the most enjoyable things we do," he says.

"People are very friendly when we speak to them in Sango," he adds. "They are extremely honest for the most part, and we usually receive a small gift, an extra measure of what we're buying."

One difficulty Sandstrom admits he has experienced is a timidity and tenseness in expressing himself in foreign languages. "For others, this poses no problem and I envy people like that," he remarks. "But everyone has a style and a medium of expression and the idea is to become relaxed and efficient with your own particular way."

Sandstrom, one of about 95 Peace Corps volunteers in the CAR and 5,000 worldwide, advises prospective Peace Corps volunteers "to go into the whole thing as loose as you possibly can. For me here," he notes, "it is instants of appreciation that make it all worthwhile a smile here, a touch there, a shared joke the more you can keep your mind free enough to keep stringing these little experiences together, the better you will be received."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBraving the Alps

March 1984 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Public Policy: The Washington Internship Program

March 1984 By Frank Smallwood '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

March 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

FeatureThose Championship Seasons

March 1984 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Art

March 1984 By Monica Louise Latini '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

March 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower