Saturday mornings were made for art. They somehow always seem to be the sunniest time of the week. For five straight days I lock myself in a library. Finally Saturday arrives. There are minimal obligations and work can always be postponed until the bells toll on Sunday reminding me that Baker Library is still an integral part of my life. Lying in bed, I recall some anxious weeknights. I remember the blank feelings I received from my stark ceiling the whiteness broken only by an ugly, plaster-encased wire running the most indirect route around the room, providing the bulbous institutional fixture in the center of the ceiling with electricity. The intense ugliness of what I see above me contrasts sharply with the beautiful sunshine streaming in the window. A vision of what I could be looking at flashes through my mind. I climb out of my six-foot loft, a personal addition to my standard dormitory room which would have made Michelangelo jealous, and grab my watercolors and a cup of water before the vision eludes me.

P.J.'s make an excellent outfit for artistic adventure. The smockiness of them takes one back to a time when artists were unkempt characters living in shabby Montmartre studios. A pile of clothing on the floor belonging to both me and my roommate supports the fantasy.

The first stroke of the brush transforms the oppressive ceiling into a giant canvas. There is no feeling of constraint, for there are virtually no boundaries. One idea may inspire another, figures may multiply and scenery may become expansive without the fear of paper running out. If an edge is reached, a mere 90-degree turn of the brush extends the canvas by another 96 square feet.

Eventually, the inspiration fades. It's time to put away the paints, for forced inspiration is contradictory. After a cheerful cleanup and shower, I'm ready to go out into the sunshine. I know I'll pay for my spontaneity later in the Housing Office, but life is full of trade-offs.

"Monica, did you get the note from Housing today?"

My roommate looks at me accusingly over her Marx-Engels reader. She's been through this before. She's thinking of the fines involved. Because of these fines, she resents my creativity.

"Yes, Linda. Don't worry. I'll go talk to that guy in the Housing Office this afternoon."

Later on that day, "that guy" assumes the respectful title of Mr. Myron Cummings a man who knows both me and my paintbrush well.

Dartmouth stresses the need for a liberal arts education and then denies its students the same. For example, only eight of the thirty-six art courses offered not including "advanced work in ... " courses are visual studies courses. Yet, even this number is deceptively high. One of these courses requires three prerequisites, all from the remaining seven. Considering that most students take only thirtythree courses as an undergraduate, this situation severely limits the number of students who are able to take these courses without committing themselves to either a straight or modified art major.

Even getting into these visual studies courses is a hassle. Two italicized lines in Officers, Regulations, and Courses make this clear right from the start:

A student must consult withProfessor Wysocki concerning admission to all courses in visual studies. All courses are limited in enrollment and require asignature on elective cards at thetime of course election. Many students are either automatically rejected or wait-listed for a year. This in itself illustrates the large number of students interested in the visual studies. And a year's wait-listing might as well be an outright rejection for most students, considering the diversity of our individual Dartmouth Plans.

For the student who is lucky enough to get into either Art 10, 15, or 16 the only entry level courses expectations are not often realized. "Forced creativity" is the rule rather than the exception. Too many late nights I have found myself sitting in the attic of Hallgarten drawing the inside of a cabbage.

Extracurricularly, the outlooks are just as grim for artists at this school. Student exhibitions do exist, but they tend to display only the works of students who have taken a visual studies course. My sketch of a celery stalk made in class was chosen for one such exhibition, yet a far superior pastel of my roommate, done one random evening, remains hidden in my bedroom. Pastel was not one of the media we explored in Art 15.

Dartmouth houses a multitude of closet artists who, given the oportunity, may be willing to display their masterpieces. Informal student groups have tried to combat this problem in past years, but lack of structure and College recognition turn these groups into temporary clubs which tend to dissolve with the graduation of their charter members. The Collis Center hosts single artist exhibitions in their cases and their cafe, but how many of us amateurs can boast a complete collection?

So what alternative is there for students who wish to express themselves in the form of visual presentation? They scream at you when you first move into your room Freshman Week. Four white walls and a white ceiling: an artist's dream. An outrageous combined rent of $1635 per term high even by city standards justifies the urge to personalize.

Mr. Cummings finds himself on the fourth floor of Russell Sage for his routine dorm inspection. He seriously asks me, "You wouldn't paint your walls at home, would you?"

I seriously answer, "I would if they were white."

He fires the question meant to cut deep next.

"What do you think the alumni are going to think about this over Commencement and Reunions?"

The alumni the group of unnamed people we are taught to respect as undergraduates. Successes. The men and women who keep our school financially in the black. Yet, in order to become alumni, these revered elders at one time had to be undergraduates. They too must have felt frustrated in their artistic attempts. Having worked as a dorm clerk during C&R, I've heard many alumni complain about the bareness of the rooms. One June, a '32 asked me how we stood living in rooms that looked like cell blocks at Attica.

I tell Mr. Cummings the alumni will appreciate my murals.

He tells me the Housing Office does not. I'm given until finals are over to repaint the walls and ceiling with institutional white latex. Otherwise, Housing will do the job for me and tack a few hundred dollars on both my roommate's and my college bills to cover the cost of paint and workmen. As I roll over the oceanic scene on the ceiling with latex, I wonder how famous Dartmouth would be in the artistic world if Jose Clemente Orozco had been an undergraduate rather than an artist in residence.

Three months later, the Housing Office buries my work with yet another coat of paint. Every fall the walls are repainted for the incoming Freshman. "It's easier than washing them," the little men in white claim. As I move into the room across the hall, I'm doubly depressed. Both my inspired artistic expression and my forced obliteration of the same were wasted. The little men roll white over the ceilings and the walls with or without just cause.

That winter when Mr. Cummings came to inspect Russell Sage, I did not disappoint him. Again murals covered the ceiling and walls of my room. That time, however, the deadline was more strict. Cover-up had to be done a week before finals. The logic for this escapes me. Perhaps they felt if I had one more thing to worry about during finals, I would be deterred from committing the same crime over and over.

At 11:00 a.m. Mr. Cummings knocks on the door, then lets himself in. I had been painting over until 3:00 a.m. that same morning and I still lie in bed, exhausted and depressed. It was something I had to do though, if only for Linda's sake.

"Do you want to talk now or later?" he asks from the living room.

I jump out of my loft in my P.J.'s still splattered with turquoise, magenta, and violet from earlier, better times. I show him the freshly painted, starkwhite walls and he gives me a verbal pat on my back for obliterating my works. When he leaves, I glumly muse that my murals are gone. No longer will I be able to spend my anxious nights admiring my work, using it to inspire me in other aspects of my liberal arts education. All that is left are the spots on my Montmartre uni. I reach into my desk drawer for a Kleenex.

My hand absently shifts through the rubble. A smile slowly spreads across my face as I notice what sits underneath my Kleenex box my watercolors.

The first time Mr. Cummings had visited me, I had thrown them out when he left. I wanted to remove temptation. But later I realized my folly. The temptation is not an evil one. It is merely a desire to express artistic tendencies in one of the few ways

available to the average Dartmouth student. When first arriving on the Hanover Plain, one is immediately struck by the beauty of the College and the area surrounding the campus. Such beauty is too strong an inspiration to allow academic or administrative structure to repress individual artistic tendencies. I retrieved my paints from the trash thinking that I would sooner send Housing my ear in a box than give up my spontaneous creativity.

Now, I check my supply. "There's plenty left, Mr. Cummings," I mutter as I crawl back into my loft. Staring at the now blank ceiling, I plan my life. For today, I will buy a new paintbrush; the old one is starting to shed a little. For the future, I think I'll have six kids and send them all to Dartmouth armed with magic markers in one hand and a box of Peacock Watercolors, just like mine, in the other.

Monica Louise Latini is an English major from Cape Elizabeth, Maine. She is,as her illustrative and lively narrativereveals, also a somewhat frustrated artist.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBraving the Alps

March 1984 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Public Policy: The Washington Internship Program

March 1984 By Frank Smallwood '51 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA New in the Neighborhood

March 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

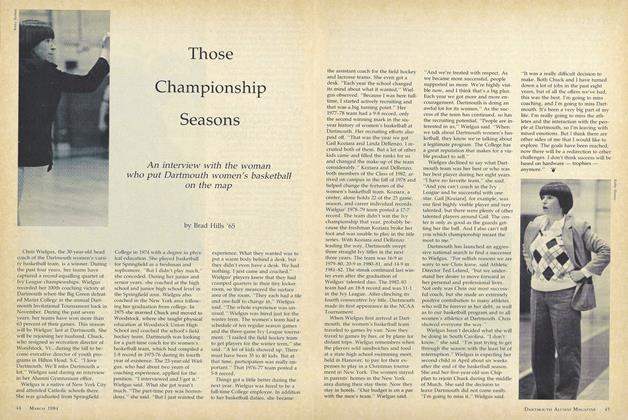

FeatureThose Championship Seasons

March 1984 By Brad Hills '65 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

March 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower -

Class Notes

Class Notes1947

March 1984 By Ham Chase