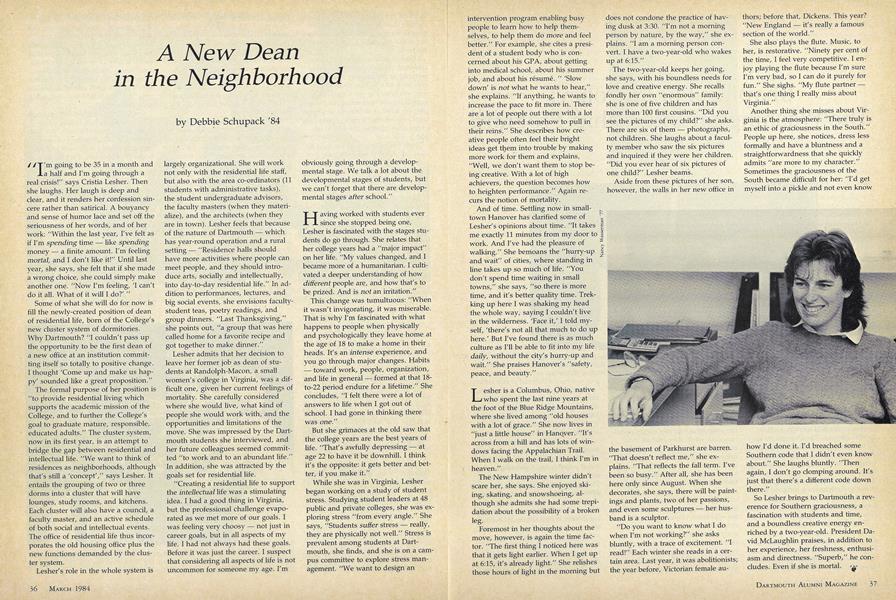

"I'm going to be 35 in a month and a half and I'm going through a real crisis!" says Cristia Lesher. Then she laughs. Her laugh is deep and clear, and it renders her confession sincere rather than satirical. A bouyancy and sense of humor lace and set off the seriousness of her words, and of her work: "Within the last year, I've felt as if I'm spending time like spending money a finite amount. I'm feeling mortal, and I don't like it!" Until last year, she says, she felt that if she made a wrong choice, she could simply make another one. "Now I'm feeling, 'I can't do it all. What of it will I do?' "

Some of what she will do for now is fill the newly-created position of dean of residential life, born of the College's new cluster system of dormitories. Why Dartmouth? "I couldn't pass up the opportunity to be the first dean of a new office at an institution committing itself so totally to positive change. I thought 'Come up and make us happy' sounded like a great proposition." The formal purpose of her position is "to provide residential living which supports the academic mission of the College, and to further the College's goal to graduate mature, responsible, educated adults." The cluster system, nOw in its first year, is an attempt to bridge the gap between residential and intellectual life. "We want to think of residences as neighborhoods, although that's still a 'concept'," says Lesher. It entails the grouping of two or three dorms into a cluster that will have lounges, study rooms, and kitchens. Each cluster will also have a council, a faculty master, and an active schedule of both social and intellectual events. The office of residential life thus incorporates the old housing office plus the new functions demanded by the cluster system.

Lesher's role in the whole system is largely organizational. She will work not only with the residential life staff, but also with the area co-ordinators (11 students with administrative tasks), the student undergraduate advisors, the faculty masters (when they materialize), and the architects (when they are in town). Lesher feels that because of the nature of Dartmouth which has year-round operation and a rural setting "Residence halls should have more activities where people can meet people, and they should introduce arts, socially and intellectually, into day-to-day residential life." In addition to performances, lectures, and big social events, she envisions facultystudent teas, poetry readings, and group dinners. "Last Thanksgiving," she points out, "a group that was here called home for a favorite recipe and got together to make dinner."

Lesher admits that her decision to leave her former job as dean of students at Randolph-Macon, a small women's college in Virginia, was a difficult one, given her current feelings of mortality. She carefully considered where she would live, what kind of people she would work with, and the opportunities and limitations of the move. She was impressed by the Dartmouth students she interviewed, and her future colleagues seemed committed "to work and to an abundant life." In addition, she was attracted by the goals set for residential life.

"Creating a residential life to support the intellectual life was a stimulating idea. I had a good thing in Virginia, but the professional challenge evaporated as we met more of our goals. I was feeling very choosy not just in career goals, but in all aspects of my life. I had not always had these goals. Before it Was just the career. I suspect that considering all aspects of life is not uncommon for someone my age. I'm obviously going through a developmental stage. We talk a lot about the developmental stages of students, but we can't forget that there are developmental stages after school."

Having worked with students ever since she stopped being one, Lesher is fascinated with the stages students do go through. She relates that her college years had a "major impact" On her life. "My values changed, and I became more of a humanitarian. I cultivated a deeper understanding of how different people are, and how that's to be prized. And is not an irritation."

This change was tumultuous: "When it wasn't invigorating, it was miserable. That is why I'm fascinated with what happens to people when physically and psychologically they leave home at the age of 18 to make a home in their heads. It's an intense experience, and you go through major changes. Habits toward work, people, organization, and life in general formed at that 18-to-22 period endure for a lifetime." She concludes, "I felt there were a lot of answers to life when I got out of school. I had gone in thinking there was one."

But she grimaces at the old saw that the college years are the best years of life. "That's awfully depressing at age 22 to have it be downhill. I think it's the opposite: it gets better and better, if you make it."

While she was in Virginia, Lesher began working on a study of student stress. Studying student leaders at 48 public and private colleges, she was exploring stress "from every angle." She says, "Students suffer stress really, they are physically not well." Stress is prevalent among students at Dartmouth, she finds, and she is on a campus committee to explore stress management. "We want to design an intervention program enabling busy people to learn how to help themselves, to help them do more and feel better." For example, she cites a president of a student body who is concerned about his GPA, about getting into medical school, about his summer job, and about his resume. " 'Slow down' is not what he wants to hear," she explains. "If anything, he wants to increase the pace to fit more in. There are a lot of people out there with a lot to give who need somehow to pull in their reins." She describes how creative people often feel their bright ideas get them into trouble by making more work for them and explains, "Well, we don't want them to stop being creative. With a lot of high achievers, the question becomes how to heighten performance." Again recurs the notion of mortality.

And of time. Settling now in smalltown Hanover has clarified some of Lesher's opinions about time. "It takes me exactly 11 minutes from my door to work. And I've had the pleasure of walking." She bemoans the "hurry-up and wait" of cities, where standing in line takes up so much of life. "You don't spend time waiting in small towns/' she says, "so there is more time, and it's better quality time. Trekking up here I was shaking my head the whole way, saying I couldn't live in the wilderness. 'Face it,' I told myself, 'there's not all that much to do up here.' But I've found there is as much culture as I'll be able to fit into my life daily, without the city's hurry-up and wait." She praises Hanover's "safety, peace, and beauty."

Lesher is a Columbus, Ohio, native who spent the last nine years at the foot of the Blue Ridge Mountains, where she lived among "old houses with a lot of grace." She now lives in "just a little house" in Hanover. "It's across from a hill and has lots of windows facing the Appalachian Trail. When I walk on the trail, I think I'm in heaven."

The New Hampshire winter didn't scare her, she says. She enjoyed skiing, skating, and snowshoeing, although she admits she had some trepidation about the possibility of a broken leg.

Foremost in her thoughts about the move, however, is again the time factor. "The first thing I noticed here was that it gets light earlier. When I get up at 6:15, it's already light." She relishes those hours of light in the morning but does not condone the practice of having dusk at 3:30. "I'm not a morning person by nature, by the way," she explains. "I am a morning person con- vert. I have a two-year-old who wakes up at 6:15."

The two-year-old keeps her going, she says, with his boundless needs for love and creative energy. She recalls fondly her own "enormous" family: she is one of five children and has more than 100 first cousins. "Did you see the pictures of my child?" she asks. There are six of them photographs, not children. She laughs about a faculty member who saw the six pictures and inquired if they were her children. "Did you ever hear of six pictures of one child?" Lesher beams.

Aside from these pictures of her son, however, the walls in her new office in the basement of Parkhurst are barren. "That doesn't reflect me," she explains. "That reflects the fall term. I've been so busy." After all, she has been here only since August. When she decorates, she says, there will be paintings and plants, two of her passions, and even some sculptures her husband is a sculptor.

"Do you want to know what I do when I'm not working?" she asks bluntly, with a trace of excitement. "I read!" Each winter she reads in a certain area. Last year, it was abolitionists; the year before, Victorian female authors; before that, Dickens. This year? "New England it's really a famous section of the world."

She also plays the flute. Music, to her, is restorative. "Ninety per cent of the time, I feel very competitive. I enjoy playing the flute because I'm sure I'm very bad, so I can do it purely for fun." She sighs. "My flute partner that's one thing I really miss about Virginia."

Another thing she misses about Virginia is the atmosphere: "There truly is an ethic of graciousness in the South." People up here, she notices, dress less formally and have a bluntness and a straightforwardness that she quickly admits "are more to my character." Sometimes the graciousness of the South became difficult for her: "I'd get myself into a pickle and not even know how I'd done it. I'd breached some Southern code that I didn't even know about." She laughs bluntly. "Then again, I don't go clomping around. It's just that there's a different code down there."

So Lesher brings to Dartmouth a reverence for Southern graciousness, a fascination with students and time, and a boundless creative energy enriched by a two-year-old. President David McLaughlin praises, in addition to her experience, her freshness, enthusiasm and directness. "Superb," he concludes. Even if she is mortal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBraving the Alps

March 1984 By Jack Aley '66 -

Feature

FeatureShaping Public Policy: The Washington Internship Program

March 1984 By Frank Smallwood '51 -

Feature

FeatureThose Championship Seasons

March 1984 By Brad Hills '65 -

Article

ArticleThe Price of Art

March 1984 By Monica Louise Latini '84 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1963

March 1984 By Harry R. Zlokower -

Class Notes

Class Notes1947

March 1984 By Ham Chase

Debbie Schupack '84

-

Article

ArticleFreshman Book to Aegis

November 1983 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleWhy "Why Not?"

JANUARY/FEBRUARY 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleIt's Just Like Talking to People

APRIL 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Feature

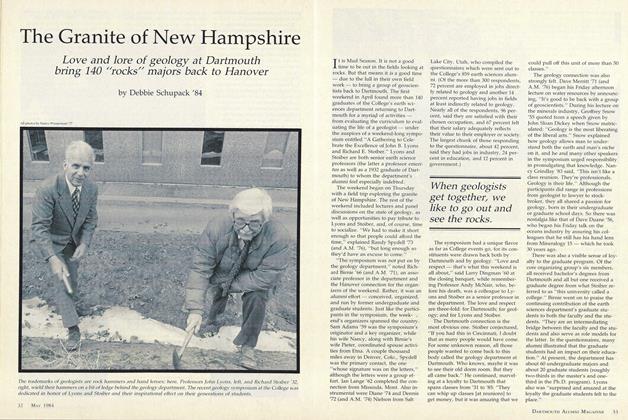

FeatureThe Granite of New Hampshire

MAY 1984 By Debbie Schupack '84 -

Article

ArticleGetting Ahead on the Mommytrack

OCTOBER 1990 By Debbie Schupack '84