A glimmer of hope at Hitchcock

At least one out of every 11 Americans over the age of 65 suffers from the brain disorder known as Alzheimer's disease.

After heart disease, cancer, and stroke, Alzheimer's is the fourth largest cause of death among the elderly. Though the disease usually strikes after age 65, the elderly are not the only potential sufferers. Alzheimer's can hit people in their 40s, and there have even been cases in their 20s.

Two and a half million elderly Americans have the disease and it claims 120,000 lives annually. The disease is irreversable, and its causes are unknown; once someone gets it, there is no way of stopping the degeneration it causes. Unfortunately, efforts to develop an effective cure have made little progress.

A group at the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center, led by neurosurgeon Dr. Robert Harbaugh, recently developed a method of drug infusion to the brain that has potential application for many diseases, including Alzheimer's. Even though their findings are only preliminary and somewhat subjective, their work has yielded some interesting results with Alzheimer's patients. The results of the Harbaugh study will not be "concrete" for at least another year, but Harbaugh said the group is "encouraged enough to continue."

Part of the problem with Alzheimer's is that it has symptoms which are not unique to its sufferers. The loss of memory and motor control as well as the lack of initiative could be the result of a thyroid condition, multiple sclerosis, or depression just as easily as they could be laid to Alzheimer's. Since the disease is a brain disorder, the only way to be absolutely sure is to examine a microscopic slice of the patient's brain.

In 1906, Dr. Alois Alzheimer discovered twisted nerve cell fibers he called "neurofibrillary tangles" in the brain of a patient with advanced senility. Alzheimer postulated that the tangles were the cause of the senility, but the question of what causes the tangles has remained unresolved for nearly 80 years. It's not even clear whether the clusters are the cause of the disease or one of its effects.

While the disease is irreversible and incurable at the moment, some things have improved in the quest for answers. First of all, the federal government has increased its funding of Alzheimer's research from under $4 million in 1976 to $37.1 million in 1984. More importantly, in the last few years researchers made significant progress in understanding the disease. In 1976 British scientists discovered that Alzheimer's victims have a deficiency in a chemical called acetylcholine in their brains. Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter responsible for carrying impulses between nerve cells in the brain; without it, the brain will slow down and memory lapses will begin to occur.

Memory lapses are the first signs that the disease may be setting in. After the memory deteriorates, the patient suffers a breakdown in the ability to think: routine tasks that one might do from memory as simple as combing one's hair can't be done anymore.

Soon the victim loses the ability to reason or make judgments. For example, he or she will dress to go out in summer clothing in the middle of winter, or confuse the hot and cold water handles in a shower and scald himself. The final step is loss of control of bodily fucntions, a situation that makes the patient totally dependent on others.

The worst part of Alzheimer's, though, is the agonizing rate at which it claims its victims. On the average, it can take six to eight years for the total degeneration to occur; but in some cases it can take as long as 20 years.

Research groups around the world are exploring various hypotheses to cure the disease and to learn more about where it comes from. Since the British discovery, many scientists have reasoned that the disease could be controlled and treated if the effects of acetylcholine could be mimicked by drugs in the brain. Some of the most encouraging work in testing this hypothesis is being done by Dr. Harbaugh, Dr. David Roberts, Dr. Richard Saunders, Dr. Charles Culver, all MDs on the Dartmouth Hitchcock staff, and Mark Johnson, Ph.D., a visiting assistant professor of psychiatry at the Dartmouth Medical School. In October, 1984 the group published an article in Neurosurgery saying they had achieved "encouraging preliminary results" with a new method of administering drugs.

Following the idea that the level of acetylcholine in the brain might have something to do with Alzheimer's, but discouraged that oral use of acetylcho-line-like drugs had been ineffective, Harbaugh decided to implant a small pump in the patient and inject the drugs directly into the brain. "Not enough of the drug was getting to the brain through the blood stream," he said.

Dr. Dennis Coombs, an anesthesiologist at DHMC, had been experimenting with pumps for use in treating pain in cancer patients through spinal narcotics when Harbaugh approached him in 1980 about their possible use for Alzheimer's. Coombs had been building his own pumps, but had recently switched to pumps made by Infusaid of Norwood, Mass., and he introduced Harbaugh to them. Harbaugh began using the pumps in animal research which he funded himself through a $2500 loan. Eventually, Harbaugh received a grant from Infusaid to continue the project.

In Harbaugh's procedure, the pump, about the size of a hockey puck, is implanted in the patient's abdomen and a small tube is run to the skull behind the ear. In the skull a tiny hole is drilled that allows a catheter to run into the brain. The pump is filled with bethanechol chloride, the mimicking drug, and body warmth forces the drug up the tube to the catheter which feeds the drug to the cerebrospinal fluid in the brain. The operation is a "fairly easy one on the patient," according to Roberts. It requires a hospital stay of only a few days for observation, with the pump being refilled by injection every three weeks. And according to Harbaugh, "the pump doesn't get in the way of anything. It allows people to go about their normal activities."

Harbaugh and his team screened 15 potential recipients for their experimental procedure, settling on four patients for the initial feasibility study. The four two men and two women ranging in age from 64 to 73 all suffered Alzheimer's disease for at least three years. All were at least "moderately affected," said Teddi Reeder, a nurse involved with the study. The four were run through a battery of psychiatric tests before surgery to establish a baseline for comparison.

The first of the four implants was conducted in July 1983 and the last in December 1983. Harbaugh and his team then began observing the patients to see the results of the procedure. "We were just as concerned with the performance of the method itself as we were with the treatment of the disease," Harbaugh said. In their testing of the pumps and infusion method, Drs. Harbaugh, Roberts, and Saunders substituted placebos for the bethanechol chloride at regular intervals to provide themselves with a method of control. When the patients received their refilling injections, they were interviewed as were members of their families to see if any improvement had taken place.

Three of the four initial pump recipients were headed to nursing home care before their operations; now, 22 months later, each of them has shown some improvement from their previous condition, but only in specific areas. Harbaugh and his team are encouraged by results they obtained.

When the study was published in October, many took the results to mean that a cure for Alzheimer's had been found, which was not the case. Harbaugh meant only to establish the feasibility of the infusion method as a potential treatment. "Any kind of significant results are jumped at because everybody wants to see something done," Harbaugh said. "We never said we had cured the disease, yet some people took what we said to be just that." Since the patients' families saw either improvements in their condition or at least a stabilization they thought the disease had been cured, but objective psychiatric data show that cognition and memory ability did not actually improve.

The psychiatric section of the study was run by Drs. Culver and Johnson. Every three weeks they interviewed the four patients and their families. Their tests covered cognition, intelligence, perception, memory, and attention, Johnson said. Results obtained before the implants were used for comparison.

The researchers discovered that the patients showed some improvement in functional health status; that is, in their ability to conduct daily living chores and live in the "daily world." There was a definite difference in the patients from their previous status, and some family members even claimed to be able to tell when their patient was on the placebo instead of the drug, Johnson said. "They said they could tell when the patient was more 'with it' and paid more attention."

However, Johnson also said that subjective results such as these are inconclusive, and that objectively, the patients had made no progress in the areas of memory, cognition, or the ability to learn. "We are excited about the reports, but there is no proof that it works," said Harbaugh. "There is no significant memory response."

The acute effect of the drug over the placebo pleases the researchers. "The best we can say about an acute effect is encouraging," Harbaugh said. "But we can't really tell whether the drug or the method will stop or slow down the disease."

"Every bit of hard evidence shows there is no change, but we are sufficiently encouraged to continue," Culver added.

And continue they have. The October results established the feasibility of drug infusion as a method for treating Alzheimer's for Harbaugh and the team, and since the initial four implants, the team has done another four and they will do seven more. Harbaugh said that for the results to be statistically significant, the group would need 40 to 50 patients too many for the group to do in Hanover.

Since they cannot conduct the full study at Mary Hitchcock Memorial Hospital, they have made arrangements for the study to be done in collaboration with several other hospitals and medical schools around the United States and Canada. Included in the group are Rush Presbyterian Hospital in Chicago, the University of Southern California, the Montreal Neurological Institute, New York University, UCLA, Western Pennsylvania in Pittsburgh, Western Kentucky, and Baylor University. The full study sample will be 100 patients according to Reeder.

The study will be funded by another grant from Infusaid and possibly by a grant from the National Institute of Mental Health. In the first study, the patients were all fairly advanced Alzheimer's cases. Harbaugh and Roberts feel the treatment will be more effective in relatively new cases of the disease, so the new groups will not be so advanced. In Johnson's words, the first study was "more hypothesis-generating than hypothesis-testing." For example, three different locations were used for the placement of the catheter into the brain, but Johnson said the team does not know enough about how these different placements might generate different results. The group is not even sure the drug bethanechol chloride is effective; it, too, will have to be tested more.

Johnson also said the team does not know enough about how different dosages effect the results. "We got different results with the different dosages, but there is no dose-response curve yet," he said. The only way to develop an accurate dose-response curve, he feels, is to have a broader base to study.

From the psychiatric end of the study, the second phase will be "double-blind" according to Johnson. The first part of the study was "single-blind"; that is, only the patients and their families did not know if they were receiving the drug or the placebo. In a double-blind test, neither the patients, their families, nor the psychiatric interviewers and testers will know what was administered. Using the double-blind method, Johnson and Culver hope to generate more objective, reliable results.

In addition, Harbaugh and his team feel that in order for the results to mean something, the patients will have to be followed and studied for a longer period of time probably at least a year.

For now, the tests have shown Dr. Harbaugh and his associates that the infusion method of delivery is a feasible idea for the treatment of Alzheimer's disease. More important to them is the notion that the infusion method could possibly apply to the treatment of other diseases, such as epilepsy, movement and psychiatric disorders, anorexia and obesity, and brain function abnormality.

As for the future, Harbaugh said he envisions the creation of an "Infusion Institute" where the method could be studied more completely. "The most important aspect is the development of a new way to deliver drugs to the central nervous system," he said.

The picture for the future of Alzheimer's is grim. By the year 2000, 21 percent of US adults will be over the age of 55 and will therefore be at risk, according to statistics from the Alzheimer's Disease and Related Disorders Association (ADRDA). ADRDA also estimates that the number of Alzheimer's victims will jump 50 percent to between three and four million. According to Dr. Harbaugh, a real understanding of the disease is a long way off, and so, unfortunately, is a cure. "But treatments," he added, "will probably get better."

"We were just as concernedwith the performance of themethod itself as we werewith the treatment of thedisease."

More important to theresearchers is the notionthat the infusion methodcould possibly apply to thetreatment of other diseasessuch as epilepsy, movementdisorders, psychiatricdisorders, anorexia andobesity, and brain functionabnormality.

Peter Blum 'B5, a former Editor of The Dart- mouth, will be a reporter for The Evans- ville Press in Indiana next year. He is fromShaker Heights, Ohio.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth College Conference Center

May 1985 By Doug Tifft -

Feature

FeatureKappa Kappa Grandpa

May 1985 By Gabrielle Guise '85 -

Article

ArticleFriend of the media

May 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Books

BooksDartmouth Authors

May 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Article

ArticleRenewal of Athletics

May 1985 By David T. McLaughlin -

Article

ArticleDavid R. Gavitt '59: Steering the Big East to the big time

May 1985 By Peter Mandel

Peter Blum '85

Features

-

Feature

Featurenotebook

JULY | AUGUST 2015 -

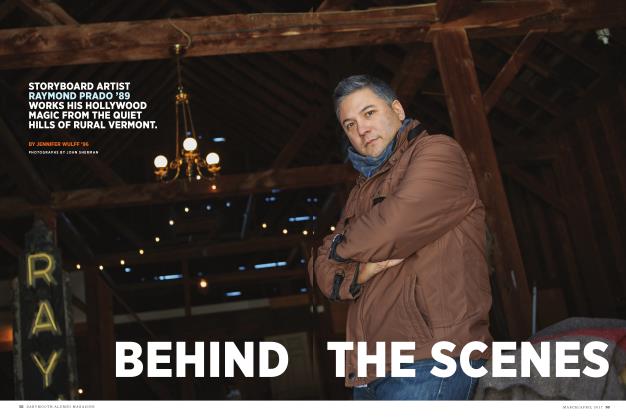

FEATURE

FEATUREBehind the Scenes

MARCH | APRIL 2017 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

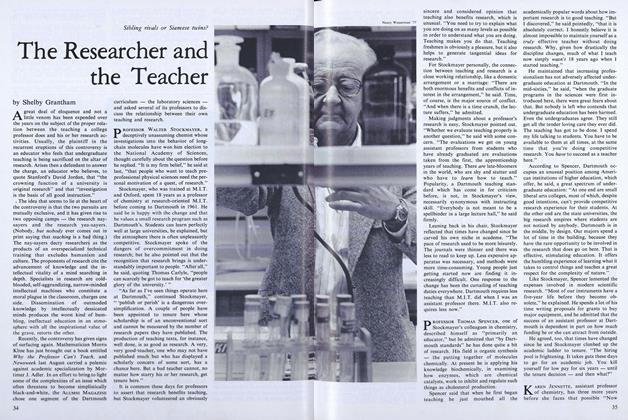

Feature

FeatureThe Researcher and the Teacher

November 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe Attraction of Peanuts

JUNE/JULY 1984 By Shelby Grantham -

FEATURE

FEATUREThe Beat of Terror

JULY | AUGUST 2015 By STUART A. REID ’08 -

Feature

FeatureSome People Are Good Skiers

February 1975 By V.F.Z.