Over the years, the signs outside Hopkins Center have announced names like Luciano Pavarotti, Bruce Springsteen, Cleo Laine, and Murray Perahia and the crowds have poured in.

But most of those who have come to Hopkins Center performances and art exhibits in the past 23 years have come because of someone whose name they've never heard. They've come because of Marion Bratesman, who has been publicizing Hopkins Center and its events since two years before the nowfamiliar arches took shape.

"When Warner Bentley first approached me about Hopkins Center, I first had to find out what Hopkins Center was" Bratesman recalls. "Everyone was talking about it, but no one seemed to know what it was. So I went to WDCR and had them do a series of interviews as tours through the building while it was being constructed. They were to be 15-minute interviews, but they were so interesting that they ended up being 45 minutes.

"We talked with theater people, music people, art people, film people. We sloshed through the terrazzo while it was being made. We told the workmen to keep right on working we wanted the sounds of the construction in the background. What I did was take the community into the Hopkins Center while it was being built, and that was how I found out what it was going to be."

That thorough, down-to-earth approach has been the hallmark of Marion Bratesman's work over the past 25 years. She researches, asks questions, digs through files, reads, listens, and watches to find out as much as she can about every artist or event she is to promote. She then sets out to share that knowledge with as many people as she can reach.

And while she long ago stopped tiptoeing through the terrazzo, much of her effort has still been directed to selling unknown quantities;

Pavarotti, Springsteen, Laine, and Perahia may be big names now, but they were on the thresholds of their careers hardly household words when they came to Hopkins Center. Pavarotti had achieved fame within opera circles, but he was no instant celebrity to Upper Valley residents. Springsteen was an unknown, even to students steeped in rock. When the signs went up announcing his appearance, the general reaction was "Who's he?"

It took a combination of quality performances and carefully orchestrated publicity to help Hopkins Center and Dartmouth College achieve an identity in the arts world.

"Hopkins Center has put Dartmouth on the map in new and different ways, and Marion is one of those largely responsible for the pinpointing on the map," says John Goyette '60. He worked with Bratesman for several years as business manager and then assistant director of Hopkins Center and is now a welltraveled arts consultant, based in New York. Time magazine theater critic William Henry III, a Yale graduate, agrees: "I thought of Dartmouth as a benighted placed where nothing took place but drinking and football. Marion changed that picture for me."

It was hardly a matter of sending out a few press releases and arranging a few radio interviews, though. From the very earliest days, it was a professional selling job. It required an odd combination of toughness and class, and Marion Bratesman, with her Madison Avenue experience and her New England background, brought both to the job.

"Coming to Hopkins Center was coming home for me," Bratesman says. Born in Hanover, she left with her family as a third-grader and grew up in Boston. With typical thoroughness, she graduated from two high schools, spending most of her senior year in Palm Beach, Fla., until just before graduation, when she was called back to Boston by her mother's serious illness and received her diploma from Dorchester High School for Girls.

After two years at Northeastern University's School of Business Administration, she began her career in a Boston advertising agency, then moved up the ladder to New York as assistant to the director of advertising for The New YorkHerald Tribune.

Homesick for Boston, she went back for a stint as production director and account executive for the Ingalls Advertising Agency, now Boston's largest, but soon returned to New York and more promotional work, including a position as advertising director for a large cosmetic company and advertising manager of its five subsidiaries.

There she became expert at organizing time: "The five subsidiaries all had board meetings on Long Island, but the company was based in New York. I had to be in New York five days a week and I had to be on Long Island five days a week."

But at the end of one summer, when she came to collect her son from a vacation with his grandmother, who had returned to live in Hanover, Bratesman decided she'd been in the city long enough. She moved back to Hanover just as the. Lebanon Regional Airport Authority was being formed and was soon at work as its public relations director in the successful effort to raise $250,000 to extend the runway. And shortly after the ribbon-cutting ceremony held in a cornfield now filled with shopping centers the Hopkins Center position came along.

Selling the arts was to be a new experience for Bratesman, but basically, she says, it wasn't a big change. "I had been brought up in advertising and public relations where everything is a product," she says. "Whether you're selling James Curley for mayor, the need for a longer runway at the airport, a cosmetic, or Friends baked beans, you're selling an idea. That's why it's not hard to switch from consumer products to the arts via an airport runway.

"And the experience I'd had especially at the cosmetic company certainly had groomed me for handling a lot of things at one time at Hopkins Center music, films, theater, and art."

But there are some important differences between selling the arts from an unestablished arts center and selling a product one can eat, wear, or ride in. Next to Bratesman, Peter Smith, the Hopkins Center director with whom she worked the longest, is probably the most sensitive to the difficulties of her job.

"Fundamentally, the job of being a publicist in an arts institution is a killing job," Smith says. "The day-to-day business of making the public aware of the arts and what the artist is doing is difficult. Sports publicists may have some of the same hassles, but the people want sports information. They are not so sure they want arts information.

"And the arts publicist is almost inevitably selling something she is at a distance from. Most other public relations work involves a product the publicist can be aware of, that is tangible. But in the arts, where all the decisions on who and what you are to sell are made in an area it's impossible for you to have an attachment to, you are in an area of having to sell on faith.

"Inevitably, there are times you're going to be let down when something you've told people they simply have to see is not something they should have had to sit through. But if you stop believing in the importance of every artist or event you're dealing with, you might as well give up. And, of course, Marion never did either give up or stop believing in everything that's coming down the path."

Arts publicists are also dealt the double whammy of having to deal with not only the egos of the artists they are publicizing but also the egos of the arts writers and commentators they must convince to spread the word they want to get out.

Fortunately for Bratesman, a sincere esteem and affection for media people and a natural inclination to hospitality have enabled her to handle difficult personalities and situations with both competence and pleasure. "I have a belief," Bratesman says, "that my best friends are all in the media. I trust the press implicitly, and I am furious when someone makes a crack against them. In order to work well with the media, you have to build mutual trust with them."

Smith says what is remarkable about Bratesman's achievement at Hopkins Center is the "frequency with which writers and representatives of the electronic media have found their way to Hanover and paid attention to what is going on. The overwhelming majority have come because of her persistence and powers of persuasion."

But representatives of Time, Newsweek, The New York Times, and the major television networks don't hop on a bus and head for White River Junction just because of the persuasiveness of an articulate publicist. As Bratesman says, trust is the key, and arriving at that point was a long, delicate process.

Her success in building those relationships is reflected in the reactions of media people who have worked with her over the years. "I consider her a friend rather than a public relations person," says Frank Avruch, host of WCVB-TV's "Sunday Open House." "She never pushes. She makes sure we know what's available, and we try to take advantage of it whenever possible. It's soft-sell but hard-sell. She gets the point across."

"She's very smart," Henry says. "She understands a lot better than most in her trade what our needs are, what we'd be interested in. She's attentive without being pushy. She pops up in the mails every once in a while reminding me of what's going on at the Hop. And she has very good instincts about who is open enough and friendly enough to make a good interview. She doesn't waste our time."

One important key to Bratesman's success with the media is the preparation and attention to detail that precede every media representative's visit to Dartmouth, the kind of advance planning that is invisible but essential to making the reporter's visit pleasant, always showing Dartmouth and Hopkins Center to best advantage.

A reporter arriving at the White River Junction bus stop doesn't have to look for a taxi Bratesman is there with her car. And if the reporter is staying overnight, she's made sure that the room assigned at the Hanover Inn overlooks the Green and has fresh flowers or a plant. When spaciou's accommodations were needed for the host of NBC's "Today" show, she convinced the manager of the Inn to vacate his suite. When an informal setting is needed for artist and reporter to get together, she opens up her own apartment.

What the reporters and photographers see in their visits is also very carefully arranged so that no guiding hand is discernible behind the photo opportunities that seem to fortuitously arise. "You're never supposed to say to a cameraman, 'There's a good shot out here,' " Bratesman says. "You just let it happen. But you make sure the oppor- tunities are there."

When Jean Pierre Rampal came to give a concert at Hopkins Center, he was trailed by reporters and camera operators for "60 Minutes." A perfect photo opportunity was set up on the lawn of Dartmouth Hall, where Rampal gave an afternoon musicale for a group from a local girls' summer camp. "There they were, right in front of Dartmouth Hall. You couldn't mistake where it was. And all those campgirls listening and talking with Rampal. You couldn't say to the cameraman, 'Look at this,' but it was set up so they'd say themselves, 'Hey, all these campgirls better get a shot of this.' And some of it got on '60 Minutes' with Dartmouth Hall in the background.

"Most of the people don't realize how many miles and miles of TV film, how many rolls of color film are shot by magazines that never get into print," Bratesman says. "You have to work very long and carefully to get that one photo, that one shot on television, that one sentence in The New York Times."

But it's not just planning and preparation that lie behind what Bratesman has achieved for Hopkins Center. A lot of it depends on instinct on knowing what to do when the plans don't run smoothly or when the artist is moody or uncooperative.

Joan Downs, formerly the music and dance critic for Time magazine and now senior editor of Connoisseur, recalls one incident that Bratesman salvaged by simply being a hostess. "I don't want to mention the name of the artist," Downs says, "but once she was dealing with a very ornery Russian musician who spoke practically no English. He was in a very bad mood for reasons we were unable to discern because of the language barrier. Everyone else was treating him with kid gloves, but Marion just used a warm, sympathetic approach. She suggested a walk around Hanover, visiting some of the shops. She knew the Russians don't have much in the way of material things. We took him to all the shops, even to a yarn shop, where he was amazed by all the wools and colors he could take home to his wife. He had a great time, buying clothes for his children and gifts for his wife.

"What she did was just treated him like a sort of houseguest rather than an internationally famous artist. He relaxed, had fun, gave a great concert, and the audience loved it."

Adaptability has been the key to salvaging several events, such as the un- derwater concert of electronic music held in the College pool. First came the problem of trying to describe the event, since such a concert had only been tried once before. Then came challenges of filming (NBC) and recording (PBS's "All Things Considered"). When the NBC camera crew discovered a dolly was needed to carry cameras around the pool, Bratesman borrowed a tea trolley from the Hanover Inn. When everyone got wet since the only way to hear the music was with one's ears underwater, Bratesman dug into her own linen supply, running to and from her apartment across the street with armloads of towels.

While "gracious" and "professional" are the two words used most frequently and unanimously by media representatives to describe Marion Bratesman, her former colleague Goyette adds "tough and demanding first of all of herself, and then of her staff and the people she works with."

She works at the pace set by her Madison Avenue training, fueled by a continuously evolving schedule of films, plays, concerts, and exhibits; a kaleidoscope of newspaper, television, and radio deadlines; the individual vagaries of the 550 media representatives who make up her mailing list; and the demands and expectations of artists who want the same exposure as Larry Bird.

To do the job as a first-rate professional, a standard she never lowers, requires the cooperation of her staff, and this has given her the reputation in some circles of being a demanding boss. But at least one former secretary, Susan Fergensen, now director of program, operations, and information for PBS-TV in Washington, is grateful for the expectations Bratesman held for her.

"She gave me my start in life," Fergensen says. "Much of what I know, I learned from her. She gave me lots of professional opportunities. When you worked for Marion, you weren't just a peon. I was a secretary, and in no time, she had me writing press releases, doing radio programs at the Hanover Inn. She was very generous with her professionalism. She has had a tremendous impact on my career and life by giving me the basic essentials for marketing to the press and a lot of polish."

Bratesman's Madison Avenue drive and blue ribbon treatment of the press have occasionally caused some raised eyebrows. If she schedules a meeting with an arts editor in Boston, it's lunch at the Ritz, and this sometimes causes resentment among colleagues.

"The answer to the question of 'Who the hell does she think she is' is that she thinks she's a representative of Dartmouth College, and Dartmouth College is a first-rank institution, so she's going to present it that way," Smith says.

And Dartmouth College as a whole not just Hopkins Center and the arts has always been uppermost in her efforts. A prime example is the seven months of quiet but intense effort that went into convincing the producers of NBC's "Today" show to film their entire New Hampshire bicentennial visit on the Dartmouth Green. That started with the idea of convincing the producers to feature the Concord String Quartet, then newly in residence at Dartmouth, on a segment of the show. It ended as a major media coup for the College.

Marion Bratesman has had an impact on Dartmouth. Because of the publicity she has generated for Hopkins Center, more and more prestigious artists were attracted to appear there. She has helped the arts center to grow from isolated obscurity to a place to which important critics are now attentive. And in the process of helping the Hopkins Center achieve identity, she has helped the College expand and change its image.

Dartmouth has had an impact on her, too. She is proud to reflect on being one of the first female officers of the College, to have been adopted by the class of '37, and to have been a freshman adviser. She has been able to live and work in an area that means home to her. Many of her colleagues, along with artists and media representatives with whom she's worked, have become her close friends. And her son, Stuart, now has Dartmouth class numerals of his own ('75) after his name.

She came to open Hopkins Center and now faces another major media event the'opening of the Hood Museum of Art in September. And then, at the end of December, 25 years to the day from when she responded to Warner Bentley's request, Bratesman will retire.

It's not the end of a career, though. Just another beginning. First, she's planning to open Bratesman Associates, her own public relations agency. And then there's the book, a germ of an idea for 12 years, put aside because she's been to busy doing it to write about it.

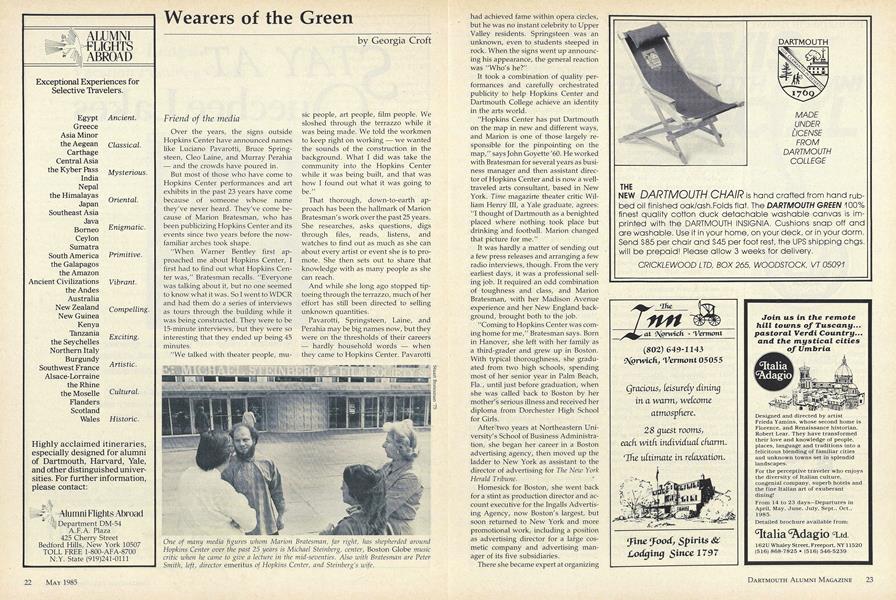

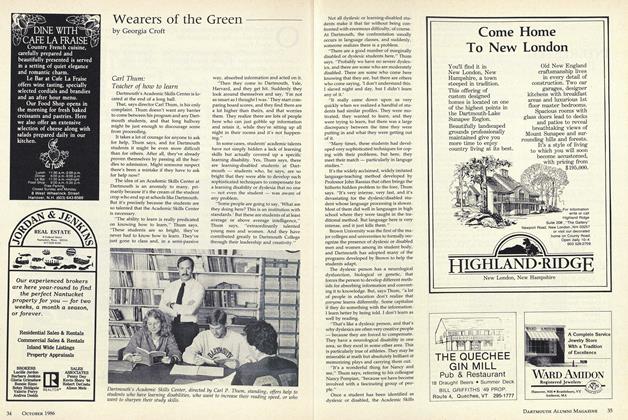

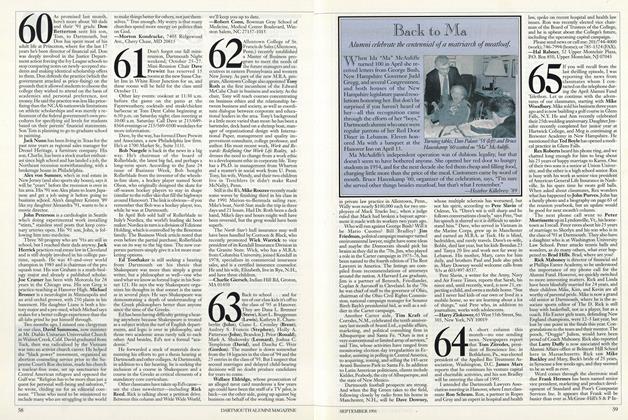

One of many media figures whom Marion Bratesman, far right, has shepherded aroundHopkins Center over the past 25 years is Michael Steinberg, center, Boston Globe musiccritic when he came to give a lecture in the mid-seventies. Also with Bratesman are PeterSmith, left, director emeritus of Hopkins Center, and Steinberg's wife.

Georgia Croft is former arts page editor andClaremont bureau chief for The Valley News and currently a free-lance writer. Shehas covered many a Hopkins Center event.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureAlzheimer's Disease

May 1985 By Peter Blum '85 -

Feature

FeatureThe Dartmouth College Conference Center

May 1985 By Doug Tifft -

Feature

FeatureKappa Kappa Grandpa

May 1985 By Gabrielle Guise '85 -

Books

BooksDartmouth Authors

May 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Article

ArticleRenewal of Athletics

May 1985 By David T. McLaughlin -

Article

ArticleDavid R. Gavitt '59: Steering the Big East to the big time

May 1985 By Peter Mandel

Georgia Croft

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

SEPTEMBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleEfrain Guigui: Well-tempered conductor

OCTOBER 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleConnie Lambert: Doyenne of "The Daily D"

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleMatthew Marshall: Keeper of the Inn

MARCH • 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleGil Fernandez '33: a fine friend to the feathered

MAY 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleCarl Thum: Teacher of how to learn

OCTOBER • 1986 By Georgia Croft

Article

-

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH SUBSCRIBES $802 FOR NEAR EAST RELIEF FUND

May 1921 -

Article

ArticleNEW MASTER'S DEGREE

MARCH 1964 -

Article

ArticleWrestling

April 1957 By Cliff Jordan ’45 -

Article

ArticleCOLLEGE DISCIPLINE

March, 1922 By EDWIN JULIUS BARTLETT '72 -

Article

ArticleBack to Ma

SEPTEMBER 1991 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Article

ArticlePSYCHOLOGY HAS BECOME BIOLOGY!

DECEMBER 1929 By Instructor Chauncey N. Allen