THE RISE OF INDUSTRIAL AMERICA: A PEOPLE'S HISTORY OF THE POST RECONSTRUCTION ERA by Page Smith '40 McGraw Hill, 1984. 965pp., $29.95

The writing of epic history on the model of the classic historians of Greece and Rome, Thucydides and Tacitus, and the more recent Europeans (especially Gibbon and his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire) has had a rich heritage in this country, too. Our own nineteenth century historians, such as George Bancroft, William Hickling Prescott, and Francis Parkman were also great practitioners of this art. Painting large themes on huge canvases, embellishing already-exciting stories, putting forth striking heroes larger than life, these masters of narrative constructed highly readable history that captured the imaginations of huge numbers of readers.

Now Page Smith takes his place in this panoply of epic historians. This is the sixth volume in his remarkable "People's History" series, following upon five previous volumes in chronological order. The period here is the post-Reconstruction second half of the nineteenth century, a period of about forty years in America's growth that changed the face of the nation. When he closes this volume with the assassination of William McKinley and the ascendancy to the presidency of Theodore Roosevelt (Smith's last page quotes a disappointed Mark Hanna: "Now, look, that damned cowboy is President of the United States"), the country had indeed been transformed by industrial capitalism.

In his introduction, Smith denominates two themes, "The Rise of Science" and "The War Between Capitol and Labor." Darwinism illustrates'the former, and Smith is at his best in his chatty and gossipy but analytically revealing chapter on the antagonists in the Darwin debate, William Graham Sumner, the Yale sociology professor, and his ideological adversary, Lester Ward, one of the founders of the National Liberal League. Sumner's laws of evolutionary development were merciless: the strong survived, the weak went down. In Sumner's essay, "What the Rich Owe the Poor," his emphatic answer was "nothing." Sumner's rival, Lester Ward, was, according to Smith, "an especially compelling figure because of his passionate 'modern' romance with Lizzie Vought." Ward's unconventional book, Dynamic Sociology, was a thoroughgoing rejection of the "natural" survivalism of Sumner. Nevertheless, Smith finds both men closer together on the evolution of man than either would admit. "Lester Ward was ... no more 'scientific' than Sumner . . . both were idealists, a species they both denounced."

Labor is Smith's "anti-thesis" of industrial capitalism, and his three chapters on the rise of the working man and his union are graphic. Full chapters are separately devoted to Haymarket and Homestead, and Smith is eloquent on both. The ingredients in the rise of industrial capitalism itself are less well covered, perhaps a small failing , given the title of the book.

Page Smith is a man of great enthusiasms, clearly delighting in telling any potentially fascinating story. He seems to sense that many of the explanatory variables in this enigmatic time period lie in social and cultural manifestations, not so much in economics or even politics. In a lively chapter on free love, we meet not only the notorious Woodhull sisters, but even more impassioned advocates-Lillian Harmon, Angela Haywood, Elmina Drake, and others. Later, Smith celebrates "the appearance of the American Woman as a new human type" and elaborates the lives of a host of remarkable individuals-Lucretia Mott, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Fanny Kemble, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Sojourner Truth, and Dorothea Dix. Another chapter celebrates the accomplishments of the famous three Adams brothers-Henry, Brooks, and Charles Francis, Jr. And another is devoted to an individual personality of the same pronunciation but different spelling, Jane Addams, and her struggle at Hull House.

Ticking off chapter headings, though, cannot do justice to the breadth and excitement of Page Smith's book. Here indeed is history writ large. This epic historian can tell a story, and one's interest does not flag even after the 900th page! Little wonder that this book and the other five all have been main selections of the Book-of-the-Month Club. Mind you, it is not a completely bal- anced picture of that period - business and even the farmers take somewhat of a back seat to literary lights and social reformers. Still, the substance is all there; professional historians will treat this work with respect, and the general reader will enjoy almost every page.

Dr. Broehl is Benjamin Ames Kimball Professor of the Science of Administration at Tuckand author of John Deere's Company.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

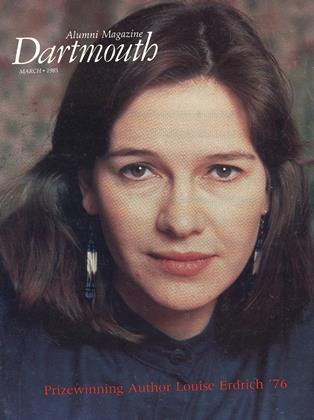

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

March 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

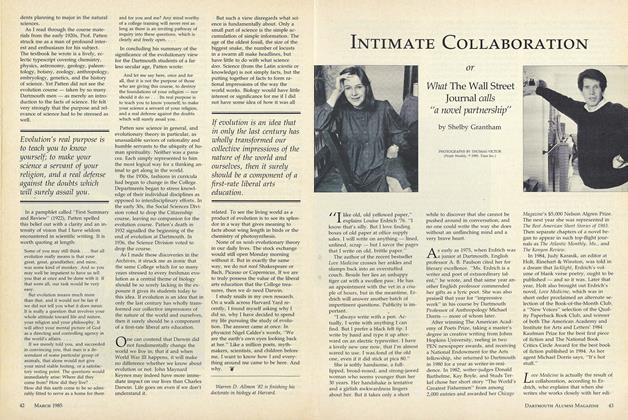

FeatureWHY STUDY EVOLUTION?

March 1985 By Warren D. Allmon '82 -

Feature

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

March 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Sports

SportsRecruiters' haul

March 1985 By Jim Kenyan -

Article

ArticleDynamite

March 1985 By Alice Dragoon '86 -

Article

ArticleRandom Thoughts

March 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85

Books

-

Books

BooksSOMMETS LITTBRAIRES FRANÇAIS.

June 1957 By HUCH M. DAVIDSON -

Books

BooksINTERNATIONAL SHIPPING CARTELS.

June 1953 By J. S. Ransmeier -

Books

BooksGENERAL ALARM: A DRAMATIC ACCOUNT OF FIRES AND FIRE-FIGHTING IN AMERICA.

NOVEMBER 1967 By JOHN A. RAND '38 -

Books

BooksDartmouth Authors

NOVEMBER • 1985 By Mark Woodward '72 -

Books

BooksOLD QUOTES AT HOME.

JANUARY 1968 By MAUDE FRENCH -

Books

BooksBLUE COLLAR MAN.

May 1961 By ROBERT H. GUEST