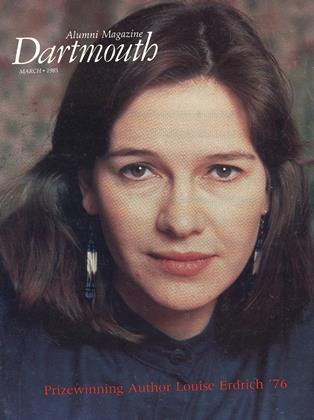

or What The Wall Street Journal calls "a novel partnership"

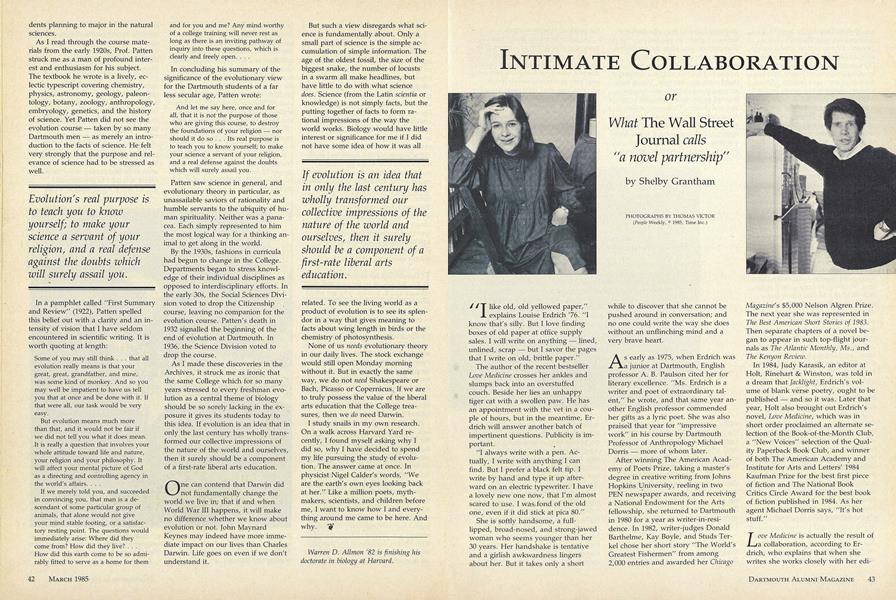

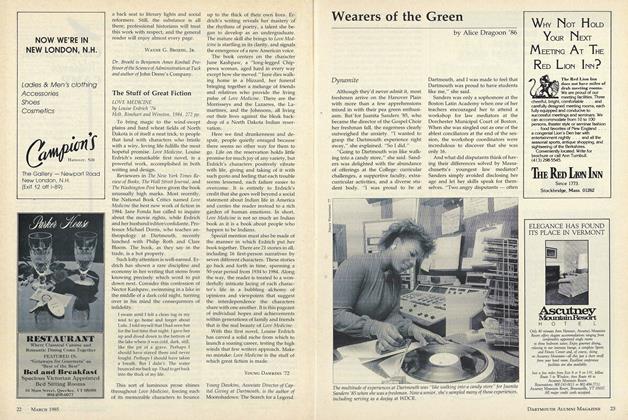

"T like old, old yellowed paper," explains Louise Erdrich '76. "I know that's silly. But I love finding boxes of old paper at office supply sales. I will write on anything-lined, unlined, scrap-but I savor the pages that I write on old, brittle paper."

The author of the recent bestseller Love Medicine crosses her ankles and slumps back into an overstuffed couch. Beside her lies an unhappy tiger cat with a swollen paw. He has an appointment with the vet in a couple of hours, but in the meantime, Erdrich will answer another batch of impertinent questions. Publicity is important.

"I always write with a pen. Actually, I write with anything I can find. But I prefer a black felt tip. I write by hand and type it up afterward on an electric typewriter. I have a lovely new one now, that I'm almost scared to use. I was fond of the old one, even if it did stick at pica 80."

She is softly handsome, a fulllipped, broad-nosed, and strong-jawed woman who seems younger than her 30 years. Her handshake is tentative and a girlish awkwardness lingers about her. But it takes only a short while to discover that she cannot be pushed around in conversation; and no one could write the way she does without an unflinching mind and a very brave heart.

As early as 1975, when Erdrich was a junior at Dartmouth, English professor A. B. Paulson cited her for literary excellence. "Ms. Erdrich is a writer and poet of extraordinary talent," he wrote, and that same year another English professor commended her gifts as a lyric poet. She was also praised that year for "impressive work" in his course by Dartmouth Professor of Anthropology Michael Dorris-more of whom later.

After winning The American Academy of Poets Prize, taking a master's degree in creative writing from Johns Hopkins University, reeling in two PEN newspaper awards, and receiving a National Endowment for the Arts fellowship, she returned to Dartmouth in 1980 for a year as writer-in-residence. In 1982, writer-judges Donald Barthelme, Kay Boyle, and Studs Terkel chose her short story "The World's Greatest Fishermen" from among 2,000 entries and awarded her ChicagoMagazine's $5,000 Nelson Algren Prize. The next year she was represented in The Best American Short Stories of 1983. Then separate chapters of a novel began to appear in such top-flight journals as The Atlantic Monthly, Ms., and The Kenyon Review.

In 1984, Judy Karasik, an editor at Holt, Rinehart & Winston, was told in a dream that Jacklight, Erdrich's volume of blank verse poetry, ought to be published and so it was. Later that year, Holt also brought out Erdrich's novel, Love Medicine, which was in short order proclaimed an alternate selection of the Book-of-the-Month Club, a "New Voices" selection of the Quality Paperback Book Club, and winner of both The American Academy and Institute for Arts and Letters' 1984 Kaufman Prize for the best first piece of fiction and The National Book Critics Circle Award for the best book of fiction published in 1984. As her agent Michael Dorris says, "It's hot stuff."

Love Medicine is actually the result of a collaboration, according to Erdrich, who explains that when she writes she works closely with her editor Michael Dorris. The basis of the collaboration, says Dorris, is talk "weeks of conversation" about a character's looks, his clothes, her jewelry. "The details of clothes and action are invented and thought about between the two of us," says Erdrich. "Often Michael notices things about people I don't."

Erdrich will do a draft, or part of one, according to Dorris, and then give it to him to read: "If she is really happy with it, she reads it aloud. Most often she just gives it to me, and I make suggestions. It's a draft at this point, an idea struggling to get out. She knows her stuff well. I am a gentle reader, a sounding board."

This intimate collaboration works, Erdrich and Dorris say, because of the similarity of their backgrounds, which they describe as "lower middle class" and "mixed blood." Erdrich was born and raised in Wahpeton, North Da- kota, one of eight children born to a Chippewa mother and a GermanAmerican father, both of whom taugh in the boarding schools run by the Bureau of Indian Affairs. Dorris, 39, grew up in many places Kentucky, Montana, Washington State and is the only child of a Modoc father and a mother from Kentucky. Neither Erdrich nor Dorris was raised on a reservation, but both often visited relatives there, and for each of them, the reservation became a sort of second home.

One result of sharing such experiences, says Dorris, is familiarity with the same idiom. That allows Dorris to be what he calls "a language testing ground" for Erdrich's work, checking what she describes as "the things people wouldn't do or say, the psychological veracity of a scene."

Overwriting is a problem for her, Erdrich feels "too many words, labored attempts at comparison, too many metaphors" and Dorris is a help there, too. He explains it this way: "Louise has the largest vocabulary of anybody I know. Esoteric words often mean exactly what she wants, but sometimes they are not words that characters would say. They jump out at you. I tell her, 'lt's a beautiful word, a great choice-but it's inconsistent with the mood.' "

Erdrich and Dorris first met in 1972, on the day each arrived in Hanover for the first time, he as an instructor in anthropology, she as an undergraduate. "Once, she took a seminar I gave," recalls Dorris. "We were friends, and after she graduated, we kept in touch with Christmas cards." Then, in 1979, Erdrich returned to Hanover to give a reading at Dartmouth. By that time, Dorris had adopted three children and become a tenured professor teaching anthropology and chairing Dartmouth's Native American Studies Program. He attended her reading: "It was exclusively poetry, which was what she was writing then. I was tremendously impressed, especially with her reading ability. Louise is as good a reader as she is a writer." Shortly thereafter, Dorris took the children to New Zealand, where he spent a sabbatical year studying early Maori-English relations. He and Erdrich corresponded.

According to a 1984 interview by Georgia Croft, Erdrich decided at 21 that she wanted to be a writer-but, she says, she didn't really go into it full-time until she was 26. "I began with a switch from poetry to fiction in 1980. I was happy about that because as was often pointed out by readers of my poetry-my poems are narrative, more like stories than poems." Before that, she says, she had not had the patience to write a novel. "At Johns Hopkins, midstream, I made a rambling stab at a novel. The burden is on me now,' I remember feeling. It was Time to Write a Novel. It was a search for a voice, a very serious, very ponderous novel. It just went on and on. I tried everything I could think of out and put everything I could think of in."

Dorris, meanwhile, had decided to try his hand at creative writing, too although as a single parent with a heavy teaching load, he found precious little time for it. "I published some poetry in The North Dakota Quarterly and Suntracks," he says. "Two of my poems were anthologized in BestAmerican Verse, and I published somelittle storiescommercial stories." He sent the stories to Erdrich for comment, and she sent him her story "Red Convertible."

Dorris returned from New Zealand, and Erdrich reappeared in Hanover as writer-in-residence under the auspices of the Native American Program. She was still at work on the manuscript of her "very serious novel," which bythen had acquired a title-Tracks. She showed it to Dorris, he recalls, and they started working on it together.

"It was exciting, beautiful writing," recalls Dorris. "Working on Tracks was fun, and I felt I was making a contribution. We started on it in January, fell in love, and were married in October."

Soon after they married, Erdrich and Dorris took their first shot at co-authorship. "We did some domestic, romantic stuff, drawn from our experience, for our own enjoyment," recalls Erdrich. "We published it under one name, a pen name, "Milou North"-Michael plus Louise plus where we live. No one seemed to think it was a strange name, which is weird. One of those stories has been in Redbook, but the rest have appeared in Europe. The general theme was domestic risis-money, an old flame showing up, that sort of thing. We thought it would make a lot of money. It didn't."

Then Dorris's aunt read about a new literary prize-the Algren Award and sent the couple a notice about it, which arrived in Cornish 12 days before the submission deadline. Erdrich and Dorris pondered this temptation to "fame and fortune" and then decided to try for it.

"Why not, we thought," recalls Errich. "Or rather Michael thought. I thought, I don't feel like it. I had a story I wanted to work on, but it was winter, we had houseguests, and the children were home because it was a school holiday. I didn't believe I could write straight through in two days. But Michael said, 'Try it, just try it. What harm is there?' "

Since her study is also the guest room, Erdrich had to set up elsewhere: "I hate having to block off a quiet part of the house, but I barricaded myself at the kitchen table behind closed doors. It seemed very depressing. But as soon as I got the first section down, I knew I couldn't stop writing. It was upsetting, and I had to go on." The first part of what became "The World's Greatest Fishermen" was drafted completely by the end of the day. "I had thought of an episode-a family reunion-with events, but no conversation or details yet," recalls Erdrich. "In the meantime, however, Michael had sprained his back, and the guests were trying to tend to themselves and to the children. Michael couldn't move he took Tylenol and tried to relax on the sitting room floor all that day and through the night. I would bring in parts of the story and he would hold them over his face to read them."

When the story was finished, just under the wire, Erdrich and Dorris typed it up together-that, says Erdrich, was hard for her: "I have a lot of trepidation about letting anyone else type up my work. It's a superstition. But it was necessary. By then, Michael had gotten up off the floor."

It won. The Erdrich-Dorris literary partnership was a success. After the Algren, one or the other of them realized that two stories Erdrich had published earlier-"The Red Convertible" and "Scales"-belonged to the same world as "The World's Greatest Fishermen," and Erdrich embarked on a second novel built around them. Thus was Love Medicine born and Erdrich launched on a tide of critical acclaim such as every writer yearns for and at the same time mistrusts. Philip Roth has declared her "greatly gifted" and found in her work "originality, authority, tenderness, and a pitiless and wild wit," and Toni Morrison has written that "the beauty of Love Medicine saves us from being devastated by its power."

The book consists of 21 stories "the related stories of the intertwined lives of two families living on a North Dakota reservation from 1934 to 1984," as the book jacket explains. A few of the stories are omnisciently narrated, but most are brilliantly immediate monologues by the characters themselves. The fact that the characters are on a reservation is important, says Erdrich but not as important as the linked themes of survival and the healing power of love: "The people are first, their ethnic background is second." It is a point all too many reviewers have missed, and, as she told The Wall Street Journal, Erdrich sometimes worries that Love Medicine "will be perceived as another 'plight of the Indian' novel." In fact, Erdrich's characters are no more "ethnic" than William Faulkner's or Eudora Welty's no less, admittedly, but certainly no more and their "plights" are universal.

The first chapter of Love Medicine is a revised version of "The World's Greatest Fishermen." It opens in 1981 with the poignant story of the last days of June Kashpaw, who dies walking home in a blizzard on Easter day. Her death occasions a family reunion at the home of her adoptive parents, Grandma and Grandpa Kashpaw, and this first chapter ends with the despoilation of a large number of freshlybaked pies. It is followed by a flashback of 47 years to 1934, when the separate lives of Marie Lazarre (Grandma) and Nector Kashpaw (Grandpa) intersect, and Nector, in "an instant that changes the course of his life," is diverted from the pursuit of a ripening Lulu Nanapush into marriage with Marie. From there the book moves forward, collecting lives right and left like a burdock burr.

Despite losing out to Marie in the matter of Nector, the wise and lusty Lulu is perhaps the most engaging character in the book. She is Dorris's favorite and has become for Erdrich "one of the most real characters I know." Lulu has "bold, gleaming blackberry eyes" and "smooth tight skin, wrinkled only where she laughed, always fragrantly powdered," and she "let the men in just for being part of the world," because she was "in love with the whole world and all that lived in its rainy arms."

"And so," she says, "when they tell you that I was heartless, a shameless man-chaser, don't ever forget this: I loved what I saw. And yes, it is true that I've done all the things they say. That's not what gets them. What aggravates them is I've never shed one solitary tear. I'm not sorry."

Lulu has a child, Gerry, by Old Man Pillager and then marries Henry Lamartine, who endures patiently her prolific production of sons not his own. Lulu's son Gerry and the young June Morrisey (later June Kashpaw, whose death opens the novel) produce their own illegitimate son, though June does not acknowledge him and he is raised by Grandma and Grandpa Kashpaw in ignorance of his origins. This son, Lipsha Morrisey, is the finest voice in the novel.

"T ipsha sat down," recounts his (cousin Albertine, "with a beer in his hand like everyone, and looked at the floor. He was more a listener than a talker, a shy one with a wide, sweet, intelligent face. He had long eyelashes. . . . Although he never did well in school, Lipsha knew surprising things. He read books about computers and volcanoes and the life cycles of salamanders. Sometimes he used words I had to ask him the meaning of, and other times he didn't make even the simplest sense. I loved him for being both ways."

Lipsha's discovery of his origins and his acceptance of them provide the ballast for this episodic novel. All the grieving and drinking and lusting and dying, the loving and torturing and birthing and joking, the working and musing and wising-up packed into this magnificent chronicle culminate in Lipsha's realization that "there was good" in his life, appearances to the contrary notwithstanding. The book is finally a celebration of such acceptances, and of patience, toleration, endurance, and passion. Reading Love Medicine is as reassuring as looking on the Sistine sybils-those ageless, full-fleshed, monumental custodians of creation, those smiling and unflappable mothers.

Lipsha, having discovered who his mother was and found his father, brings the book to its triumphant conclusion. "The sun flared up," he says, having just driven his father, escaped convict and Indian hero Gerry Nanapush, across the river into Canada. "I'd heard that this river was the last of an ancient ocean, miles deep, that once had covered the Dakotas and solved all our problems. It was easy to still imagine us beneath them vast unreasoning waves, but the truth is we live on dry land. I got inside. The morning was clear. A good road led on. So there was nothing to do but cross the water, and bring her home."

Erdrich recalls the ordering of its parts as one of Dorris's most significant contributions to Love Medicine: '"Scales' and 'The Red Convertible' were written at the same time (I collected sentences over a period of time for them-on pieces of paper, napkins at restaurants). But I let them sit a long time. I kept at the long, tortuous novel and tried to write another short story. They didn't become a novel until Michael entered the picture. I did not see that the bunch of episodes was really a long, long story. They all meshed and became a novel through a lot of late-night conversations between Michael and me until the plot was discovered."

Erdrich originally had the book in an "entirely different" form. "I didn't have it chronological," she says. "I had no real theory behind the form. I started it way in the past with 'St. Marie,' then went to the present, and then back and forth without any real structure, just a kind of personal liking." Both Dorris and the editor at Holt found Erdrich's order confusing. She resisted changing it for some time, she says, but in the end they convinced her, and now she is pleased that the book has only the one jump backwards in time.

Dorris may be, as he says, "a gentle reader"-but he is a thoroughly hard-nosed editor. "Originally," he recalls, "the 'St. Marie' chapter was a parody of Heart of Darkness. I said it should be more serious. Louise was not pleased. She rewrote it from the point of view of the sisters. Very pleased with that, she was. I could tell she was pleased she was asking me to read it now. I didn't like it. That was bad news. But I told her so, said the voice was wrong. I told her to make it first person. That is a thing I encourage her to trust. She's so good at it, she makes it so vivid, so real. She

chucked it in the other room, said she never wanted to see it again, stomped out of the house, and took a long walk in the woods. I sort of lay low and let her deal with it. The next day, there was a new draft on my desk. We had no other words about it - it just appeared there. And it was absolutely right."

"Michael has a writer's mind," says Erdrich. "I doubt if he would ever give up teaching, but he dreams books. Words overwhelm him every so often, and he has to write them down. But he has almost no time-no time. The last time he wrote, he did it in the car with one hand on the wheel. That's part of what this is all about."

Sometimes, says Dorris, he contributes "whole episodes." "Sister Leopolda in the 'St. Marie' story was a character I knew well in the fourth grade the closet, the shoe, the window-stick. And suddenly that appeared, subsumed, as a story. Louise said, 'The complete image popped out of my head.' But I recognized it."

One of the most ticklish decisions Erdrich and Dorris had to make was whether to publish jointly. They decided not to. Dorris may have his fingers in a good many pies, but Erdrich is the writer. "I read with pencil in hand," says Dorris, "and I mean pencil. The final decision is Louise's."

Dorris is easy perhaps, he feels, easier than Erdrich is about his remaining in the wings. "I'm not like a frustrated writer who wishes it were me. I'm glad it's Louise. What I do now may be the best thing I can do literarily. It's such a kick to be more than just a cheerleader. I have no problem with the fact that my name is not on the books." He shrugs. "Louise is always careful to give me credit."

When Love Medicine was sent out to an agent, it didn't move, and finally Dorris decided to become Erdrich's agent himself. As he told Wall StreetJournal reporter Helen Dudar, "I figured that chutzpah and my monomaniacal devotion would work. And it did. We made a number of magazine sales before Holt took over. I would send out sections of the book with long letters about Louise and how they should get in on the ground floor. I even had 'Michael Dorris Agency' stationery printed up. I did everything but open my shirt down to here and wear chains around my neck and call everybody baby."

Dorris admits that he learned the agent's trade by trial and error. He feels that he didn't know enough in the beginning to demand the best royalty arrangements and that he reserved for himself and Erdrich too few options. "The cover choice, for instance, we got only because of the intercession of our editor at Holt. Holt had originally selected a cover of a coffeepot in a window. It was too domestic and tame. We wanted-and finally got-a photograph of the Aurora Borealis." And their decision to subcontract the movie rights is giving them second thoughts, since they disagree with the sub-agent's recommendation of a television mini-series.

Being an agent is fun, says Dorris "the gamesmanship of it-the negotiation, the deals, having my own stationery printed." And in that role, he points out, eschewing the byline has its advantages. "Playing agent would be difficult if my name were on the book. This way, I can call up and go into raptures and sound selfless."

"The whole experience may have averted my mid-life crisis," says Dorris, grinning happily. Erdrich, too, has found the success of LoveMedicine to be a watershed: "Now I have to go back to Tracks and do without the tension that was present when I had to sit down at writers' colonies with the weight of the world on the shoulders of My Novel. It was a logical progression. I am now not as serious about writing, am much more anxious to have a good time doing it."

Dorris is also eager for her to have a good time doing it. "She's impervious to critical acclaim," he says with wry affection. "If she goes three days without working, she feels, 'l've lost my talent!' I used to take all that much more seriously than I do now. I feel like giving her a pie in the face sometimes now."

Still, it is true that Erdrich has not yet achieved her greatest ambition. "I want you to be able to buy my book at the Minot, North Dakota, airport," she says. But that, surely, is only a matter of time. Probably not much time, either.

Dorris and Erdrich live in a rambling red farmhouse in Cornish, New Hampshire, with, from left, children Abel, Persia,Madeline, and Jeffrey.

We filed in that time. Me and Grandpa. We sal down in ourpews. Then the rosary got started up pre-Mass and that's whenGrandpa filled up his chest and opened his mouth and belted outthem words.HAIL MARIE FULL OF GRACE.He had a powerful set of lungs.And he kept on like that. He did not let up. He hollered and heyelled them prayers, and I guess people was used to him by now,because they only muttered theirs and did not quit and gawk likeI did. I was getting red-faced, I admit. I give him the elbow onceor twice, but that wasn't nothing to him. He kept on. He shriekedto heaven and he pleaded like a movie actor and he pounded hischest like Tarzan in the Lord I Am Not Worthies. I thought hemight hurt himself. Then after a while I guess I got used to it,and that's when I wondered: how come?So afterwards I out and asked him. "How come? How comeyou yelled?""God don't hear me otherwise," said Grandpa Kashpaw.I sweat. I broke right into a little cold sweat at my hairlittebecause I knew this was perfectly right and for years not one damnother person had noticed it. God's been going deaf. Since the OldTestament, God's been deafening up on us. I read, see. Besides

the dictionary, which I'm constantly in use of, I had this Bibleonce.I read it.I found there was discrepancies between then andnow. It struck me. Here God used to raincth bread from clouds,smite the Philippines, sling fire down on red-light districts wherepeople got stabbed. He even appeared in person every once in awhile. God used to pay attention, is what I'm saying.Now there's your God in the Old Testament and there is Chippewa Gods as well. Indian Gods, good and bad, like tricky Nanabozho or the water monster, Missepeshu, who lives over in LakeTurcot. That water monster was the last God I ever heard to appear.It had a zoeakness for young girls and grabbed one of the Blues offher rowboat. She got to shore all right, but only after this monsterhad its way with her. She's an old lady now. Old Lady Blue. Shestill won't let her family fish that lake. ,Our Gods aren't perfect, is ivhat I'm saying, but at least theycome around. They'll do a favor if you ask them right. You don'thave to yell. But you do have to know, like I said; how to ask inthe right way. That makes-problems, because to ask proper wasan art that was lost to the Chipfiewas once the Catholics gainedground. Even now, I have to wonder if Higher Power turned itsback, if we got to yell, or if we just don't speak its language.from Love Medicine

"She chucked the piece inthe other room, said shenever wanted to see itagain, stomped out of thehouse, and took a long walkin the woods."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

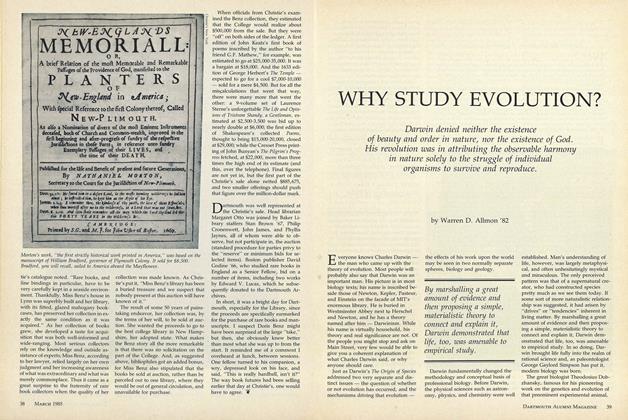

FeatureWHY STUDY EVOLUTION?

March 1985 By Warren D. Allmon '82 -

Feature

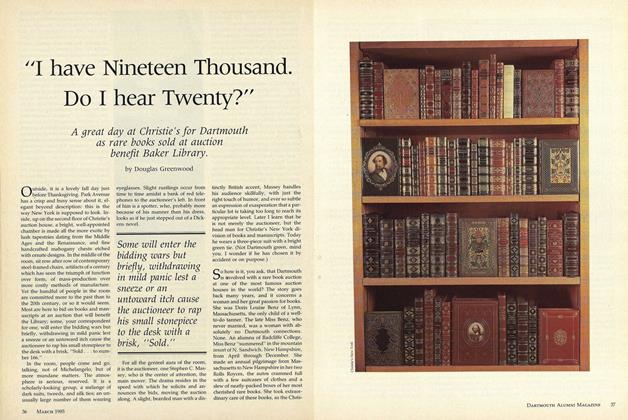

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

March 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Sports

SportsRecruiters' haul

March 1985 By Jim Kenyan -

Article

ArticleDynamite

March 1985 By Alice Dragoon '86 -

Article

ArticleRandom Thoughts

March 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

March 1985 By Robert H. Conn

Shelby Grantham

-

Feature

FeatureJohnny can't write? Who cares?

January 1977 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureThe New Classics

MARCH 1978 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Long-Deferred Promise

June 1981 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureEnd of a Golden era

APRIL 1982 By Shelby Grantham -

Article

ArticleThe Children's Own Curator

MAY 1983 By Shelby Grantham -

Cover Story

Cover StoryConsortium

APRIL 1984 By Shelby Grantham

Features

-

Feature

Feature"I Am Having a Wonderful Time"

DECEMBER 1962 -

Feature

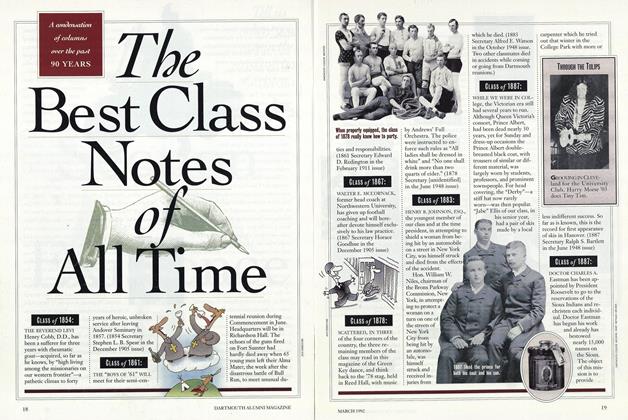

FeatureThe Best Class Notes of All Time

MARCH 1992 -

Feature

FeaturePiano Man

Sept/Oct 2004 By BONNIE BARBER -

Feature

FeatureStar Birth, Star Death, and Black Holes

February 1975 By DELO E. MOOK -

Feature

FeatureA simple mental technique... A simple mental tech... A simple mental... A simple...

February 1977 By PIERRE KIRCH -

Feature

FeatureHenderson the Beach

June 1989 By Rob Eshman '82