Darwin denied neither the existence of beauty and order in nature, nor the existence of God. His revolution was in attributing the observable harmony in nature solely to the struggle of individual organisms to survive and reproduce.

Everyone knows Charles Darwin the man who came up with the theory of evolution. Most people will probably also say that Darwin was an important man. His picture is in most biology texts; his name is inscribed beside those of Newton, Kepler, Pasteur, and Einstein on the facade of MlT's enormous library. He is buried in Westminster Abbey next to Herschel and Newton, and he has a theory named after him-Darwinism. While his name is virtually household, his theory and real significance are not. Of the people you might stop and ask on Main Street, very few would be able to give you a coherent explanation of what Charles Darwin said, or why anyone should care.

Just as Darwin's The Origin of Species addressed two very separate and distinct issues the question of whether or not evolution has occurred, and the mechanisms driving that evolution the effects of his work upon the world may be seen in two normally separate spheres, biology and geology.

Darwin fundamentally changed the methodology and conceptual basis of professional biology. Before Darwin, the physical sciences such as astronomy, physics, and chemistry were well established. Man's understanding of life, however, was largely metaphysical, and often unhesitatingly mystical and miraculous. The only perceived pattern was that of a supernatural creator, who had constructed species pretty much as we see them today. If some sort of more naturalistic relationship was suggested, it had arisen by "drives" or "tendencies" inherent in living matter. By marshalling a great amount of evidence and then proposing a simple, materialistic theory to connect and explain it, Darwin demonstrated that life, too, was amenable to empirical study. In so doing, Darwin brought life fully into the realm of rational science and, as paleontologist George Gaylord Simpson has put it, modern biology was born.

The great biologist Theodosius Dobzhansky, famous for his pioneering work on the genetics and evolution of that preeminent experimental animal, the fruit fly, once wrote that "nothing in biology makes sense except in the light of evolution." This pronouncement gives the essence of the revolution in biology brought about by Darwin's convincing demonstration that the order and structure we perceive in the living world has arisen by what he called "descent with modification" what we call evolution. Not only did Darwin's work essentially found a dozen or more new fields in biology, but he provided a common conceptual framework upon which would later be united such disparate disciplines as genetics, paleontology, systematics (the science of classifying organisms), and comparative morphology

One frequently-used measure of the success of a scientific theory is the number of seemingly unrelated observations and apparent incongruities it draws together and explains. If this ad hoc yardstick is applied, then it is incontestable that evolution is the central theme underlying all biology. Why organisms have the molecular, cellular, physiological, and morphological characteristics they do, why they live where they live and reproduce when and as they do, and how all these features relate to their fossil record becomes clear when viewed evolutionarily. Why humans have an appendix and wisdom teeth, why some whales, dolphins, and snakes have vestigial hind limbs, why some fossils resemble living organisms while others do not, can all be seen as pieces of the same great puzzle. Life on earth is over three billion years old, and for all these thousands of millenia, forces have been acting on organisms, effecting changes in the way they live and in the very shapes and forms of their bodies. In short, life has been evolving; the earth and its life are one great interrelated whole, changing together and affecting each other.

Since Darwin's time, details have been added and errata corrected. Darwin did not understand genetics, nor did he know the actual age of the earth. Evolutionary theorists still argue over the exact mechanism underlying the process of evolution, and it seems likely that that process is a good deal more complicated than Darwin ever dreamed. But the pattern documented, that all life is descended, with modification, from previous life and ultimately from the earth itself, is now well-established in professional biology and geology circles. Life has assumed its present form by the process of evolution, and we cannot ever hope to understand life except through an understanding of those processes.

Few writers have summarized the effects of the publication of The Originof Species in November 1859 better than Darwin's biographer, Peter Brent.

All of us, in other words, have been forced to accommodate ourselves to the inescapable transformation worked by his ideas ... in the space of two decades, Darwin redesigned the natural world. That is to say, he altered the way most of us in the developed world perceive the cosmic order. Himself a man who drew back from metaphysical speculation, he nevertheless gave a new significance to such abstractions as Divinity, Nature, Time, and Death. He relocated God and redefined his functions. To mankind he gave a new and perhaps diminished character. Reorganizing the history of life on his planet, he redirected humanity's gaze from the past of Eden to a future opened up by change.

Once it was clear that, like the orchids and finches and tortoises Darwin had observed, humans, too, had arisen by the processes of evolution, life's history had to be seen as a grand procession in which man is but a single marcher. He is no more and no less special than any other organism. Darwin denied neither the existence of beauty and order in nature, nor the existence of God. His revolution was in attributing the observable harmony in nature solely to the struggle of individual organisms to survive and reproduce rather than to the guidance of overarching laws or a predetermined order, and in attributing the question of the reality and actions of God to a realm beyond that of empirical science. The grandeur he saw in this view of life was that, as Brent has put it, life simply is—no more, no less. It is a system in perpetual flux, its orders and harmonies transient and everchanging, arising solely from its own volatile existence.

If Darwin and his conceptual revolution have been so important in the sciences and in society, why are we so largely ignorant of him? In 1982, a Gallup survey reported that 44 percent of Americans believed that God created man in his present form within the last 10,000 years, while nine percent believe in the theory of evolution with God not involved, and 38 percent believe that man evolved in an evolutionary process guided by God. Americans with some college education leaned two to one in favor of evolution in the survey, but nearly one-third of the college segment believed the literal biblical account of creation.

Perhaps one reason for this general lack of appreciation for the nature of the Darwinian view of life, is a general lack of emphasis on Darwin and evolution in most high schools and in many university-level biology curricula. Dartmouth is no exception to this trend. While the Department of Earth Sciences is virtually without equal in the quality of undergraduate geology education it provides, and programs and courses in the Department of Biological Sciences (especially in tropical ecology and cellular biology) are excellent, neither department has a faculty member whose primary research interest is in evolution. The only course listed in the College catalog by the biology department on evolution is offered irregularly, and there is little

emphasis in introductory courses on evolution as a central, unifying idea. One biology professor even told me once that he wasn't sure he really saw the reason why biology majors had to graduate with an understanding of evolution. While a recent interdiciplinary seminar in the government, biology, and anthropology departments called "The Nature of Human Nature" had an evolutionary emphasis, it also had a very limited enrollment.

It wasn't always this way though. From 1921 until 1936, a course called simply "Evolution" was required of all members of the freshman class at Dartmouth. The course was described in the 1931-32 course catalog as "A scientific survey course designed to acquaint the student with the nature of the universe in which he lives and the methods of science by which an understanding of this universe has been attained." It was originally under the direction of Professor William Patten, and was a companion to a course under the equally simple title of "Citizenship." Prof. James P. Poole, who, by 1931 had become Professor of Evolution, related that these were called "Orientation Courses," the evolution course designed to provide background in the natural sciences for students planning to major in the social sciences or humanities, the citizenship course designed to provide background in the social sciences to students planning to major in the natural sciences.

As I read through the course materials from the early 19205, Prof. Patten struck me as a man of profound interest and enthusiasm for his subject. The textbook he wrote is a lively, eclectic typescript covering chemistry, physics, astronomy, geology, paleontology, botany, zoology, anthropology, embryology, genetics, and the history of science. Yet Patten did not see the evolution course taken by so many Dartmouth men as merely an introduction to the facts of science. He felt very strongly that the purpose and relevance of science had to be stressed as well.

In a pamphlet called "First Summary and Review" (1922), Patten spelled this belief out with a clarity and an intensity of vision that I have seldom encountered in scientific writing. It is worth quoting at length:

Some of you may still think . . . that all evolution really means is that your great, great, grandfather, and mine, was some kind of monkey. And so you may well be impatient to have us tell you that at once and be done with it. If that were all, our task would be very easy.

But evolution means much more than that, and it would not be fair if we did not tell you what it does mean. It is really a question that involves your whole attitude toward life and nature, your religion and your philosophy. It will affect your mental picture of God as a directing and controlling agency in the world's affairs. . . .

If we merely told you, and succeeded in convincing you, that man is a descendant of some particular group of animals, that alone would not give your mind stable footing, or a satisfactory resting point. The questions would immediately arise: Where did they come from? How did they live? .... How did this earth come to be so admirably fitted to serve as a home for them and for you and me? Any mind worthy of a college training will never rest as long as there is an inviting pathway of inquiry into these questions, which is clearly and freely open. . . .

In concluding his summary of the significance of the evolutionary view for the Dartmouth students of a far less secular age, Patten wrote:

And let me say here, once and for all, that it is not the purpose of those who are giving this course, to destroy the foundations of your religion-nor should it do so . . . Its real purpose is to teach you to know yourself; to make your science a servant of your religion, and a real defense against the doubts which will surely assail you.

Patten saw science in general, and evolutionary theory in particular, as unassailable saviors of rationality and humble servants to the übiquity of human spirituality. Neither was a panacea. Each simply represented to him the most logical way for a thinking animal to get along in the world.

By the 1930s, fashions in curricula had begun to change in the College. Departments began to stress knowledge of their individual disciplines as opposed to interdisciplinary efforts. In the early 30s, the Social Sciences Division voted to drop the Citizenship course, leaving no companion for the evolution course. Patten's death in 1932 signalled the beginning of the end of evolution at Dartmouth. In 1936, the Science Division voted to drop the course.

As I made these discoveries in the Archives, it struck me as ironic that the same College which for so many years stressed to every freshman evolution as a central theme of biology should be so sorely lacking in the exposure it gives its students today to this idea. If evolution is an idea that in only the last century has wholly transformed our collective impressions of the nature of the world and ourselves, then it surely should be a component of a first-rate liberal arts education.

One can contend that Darwin did not fundamentally change the world we live in; that if and when World War 111 happens, it will make no difference whether we know about evolution or not. John Maynard Keynes may indeed have more immediate impact on our lives than Charles Darwin. Life goes on even if we don't understand it.

But such a view disregards what science is fundamentally about. Only a small part of science is the simple accumulation of simple information. The age of the oldest fossil, the size of the biggest snake, the number of locusts in a swarm all make headlines, but have little to do with what science does. Science (from the Latin scientia or knowledge) is not simply facts, but the putting together of facts to form rational impressions of the way the world works. Biology would have little interest or significance for me if I did not have some idea of how it was all related. To see the living world as a product of evolution is to see its splendor in a way that gives meaning to facts about wing length in birds or the chemistry of photosynthesis.

None of us needs evolutionary theory in our daily lives. The stock exchange would still open Monday morning without it. But in exactly the same way, we do not need Shakespeare or Bach, Picasso or Copernicus. If we are to truly possess the value of the liberal arts education that the College treasures, then we do need Darwin.

I study snails in my own research. On a walk across Harvard Yard recently, I found myself asking why I did so, why I have decided to spend my life pursuing the study of evolution. The answer came at once. In physicist Nigel Calder's words, "We are the earth's own eyes looking back at her." Like a million poets, mythmakers, scientists, and children before me, I want to know how I and everything around me came to be here. And why.

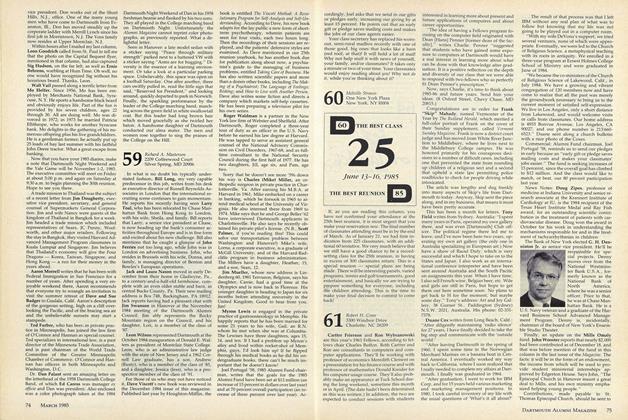

Professor William Patten, shown above in his makeshift office laboratory. His efforts inestablishing the missing link between man and lower animal forms centered on his beliefthat the key could be found in the nervous systems of vertebrates, particularly as they existedin primitive organisms.

By marshalling a greatamount of evidence andthen proposing a simple,materialistic theory toconnect and explain it,Darwin demonstrated thatlife, too, was amenable toempirical study.

Life has assumed its presentform by the process ofevolution, and we cannotever hope to understand lifeexcept through anunderstanding of thoseprocesses.

Evolution's real purpose isto teach you to knowyourself; to make yourscience a servant of yourreligion, and a real defenseagainst the doubts whichwill surely assail you.

If evolution is an idea thatin only the last century haswholly transformed ourcollective impressions of thenature of the world andourselves, then it surelyshould be a component of afirst-rate liberal artseducation.

Warren D. Allmon '82 is finishing hisdoctorate in biology at Harvard.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

March 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

March 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Sports

SportsRecruiters' haul

March 1985 By Jim Kenyan -

Article

ArticleDynamite

March 1985 By Alice Dragoon '86 -

Article

ArticleRandom Thoughts

March 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1961

March 1985 By Robert H. Conn

Features

-

Feature

FeatureA Call for Equal Opportunity

FEBRUARY 1969 -

Feature

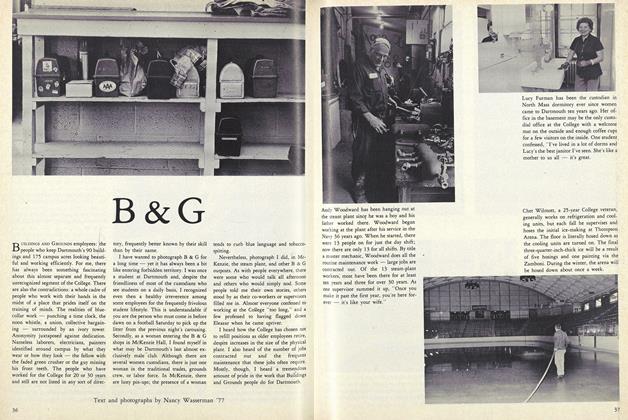

FeatureB & G

NOVEMBER 1981 -

Feature

FeatureTHE MOUNTAINEERS

Jan/Feb 2013 By BROUGHTON COBURN -

Feature

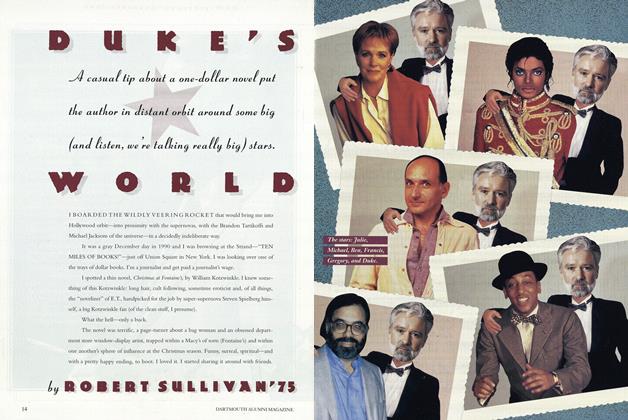

FeatureDUKE'S WORLD

February 1993 By ROBERT SULLIVAN '75 -

Feature

FeatureNon-Violent Change in Our Society

JULY 1968 By THE HON. JACOB K. JAVITS, LL.D. '68 -

Feature

FeatureStudent Workshop

MAY 1957 By VIRGIL POLING