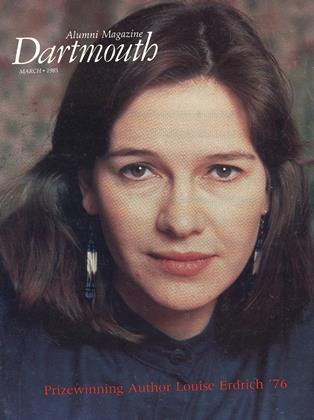

James Breeden '56 came to Dartmouth as a freshman in the fall of 1952 for several reasons: "a good chemistry department, because I wanted to be a chemical engineer; a liberal arts curriculum, which I thought would allow me to explore subjects that I was interested in like philosophy and art and literature; and north woods very much as I had known them in Minnesota, with the addition of mountains."

Breeden returned to Hanover a couple of months ago not as a chemical engineer but as dean of the Tucker Foundation. He finds the charge of the Foundation-"to support and further the moral and spiritual work and influence of the College"-"wonderful" in its scope. "For many people it would not be a focus, but it is for me," states Breeden. "By the time I'd completed the [interviewing] process, I was convinced that the Tucker Foundation was a place in which I could use my talents and skills and interests in a way in which it would be hard to imagine any other place potentially fulfilling."

He most likes to describe himself as an educator, but he has also earned his stripes as a civil rights activist, a school system administrator, and an Episcopal priest. He came back to Hanover from a post as director of a federally-funded program that deals with national educational issues affecting low-income people. He has been a leader in civil rights activism since the early sixties. He served as an administrator in Boston's public school system during the implementation of court-ordered busing. He has served as an Episcopal priest in slums in East Harlem, N.Y., and Roxbury, Mass. Along the way, he obtained a master of divinity degree from Union Theological Seminary and a doctorate in education from Harvard.

All his past experience has, Breeden feels, prepared him for the job he's just taken on. He sees the words "conscience" and "justice" as very strong guiding principles for the Tucker Foundation. "Conscience is always connected with activism," he says. "I believe the modeling of commitment is the only way one learns commitment. To model neutrality while exhorting people to commitment has always seemed to me dubious morally." Breeden explains that he once had a long debate on this issue with former Harvard president Derek Bok ("though he probably doesn't remember it"). "I argued that to take no stand on nuclear issues, to merely say they're complex, was irresponsible. I didn't care if I totally disagreed with his stand, but you don't need a figure of power and authority to tell you these are complex issues."

Breeden goes on to say that "if the Tucker Foundation does its job well, those whose consciences propel them to action will find a place here not only of protection but also of criticism-a place where the dictates of conscience have to be tested within the whole community. So I welcome conscientious activism from the left as well as the right as well as the middle. I want the Tucker Foundation to be a place where those differences in views can be aired vigorously and tested thoroughly."

Many of the projects Breeden has in mind as ways of implementing those ideas focus on "the potential of the Upper Connecticut Valley as a place for the students to explore and perhaps contribute to." He'd like to see the continuation of such programs as Big Brother/ Big Sister, a wood-chopping network to provide fuel for low-income families, and a prison visitation project. He's also got a few new ideas, including using Dartmouth's computing resources to set up an electronic bulletin board among area social service agencies and churches to share ideas and plans without having to "drive two hours to get to a one-hour meeting."

Another of Breeden's plans is to use the College's foreign study programs as "a resource for ethical and moral and policy reflection." He sees tapping students' experiences in existing programs, instead of setting up special programs within the Foundation, as a good way of achieving cross-cultural reflection in times of tight budgets.

He gives another example of a way he'd like to see the Tucker Foundation helping students make connections between experiences in the classroom and experiences in the outside world. He notes three seemingly unrelated issues: this spring's senior symposium on Third World development; the famine in Ethiopia; and a new program whereby students can contribute funds from unused Thayer meal punches to emergency food shelves in the Upper Valley. Breeden feels that the Tucker Foundation is the perfect place to make the connection of "hunger and lack of food or money" among these three issues and to impel students to some sort of action perhaps initiating a letter-writing campaign to legislators.

He concludes by elaborating slightly on a much-quoted aphorism by Rene Dubos, who said, "Think globally; act locally." Breeden says that the Tucker Foundation is here to help students "try to understand global implications, but try to find the action [they] can take locally and personally."

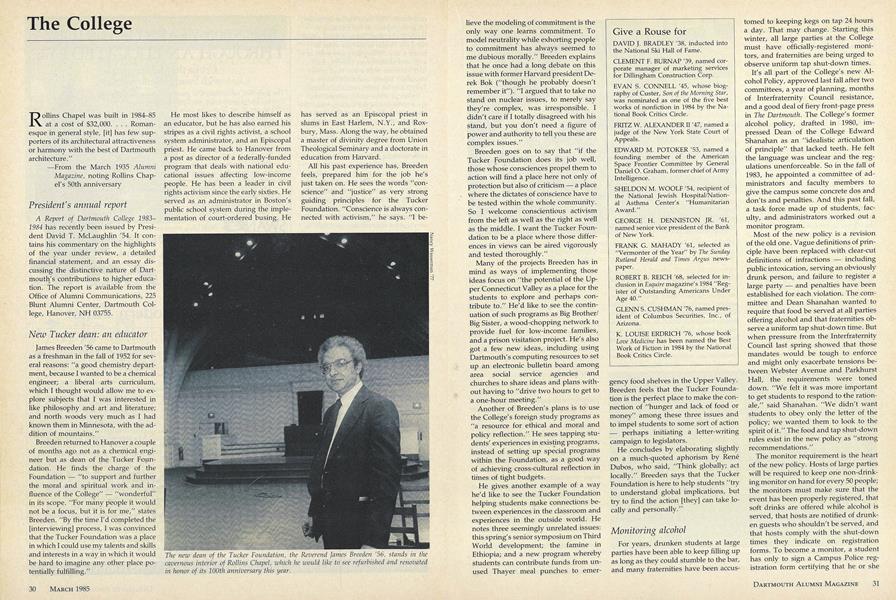

The new dean of the Tucker Foundation, the Reverend James Breeden '56, stands in thecavernous interior of Rollins Chapel, which he would like to see refurbished and renovatedin honor of its 100 th anniversary this year.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureIntimate Collaboration

March 1985 By Shelby Grantham -

Feature

FeatureWHY STUDY EVOLUTION?

March 1985 By Warren D. Allmon '82 -

Feature

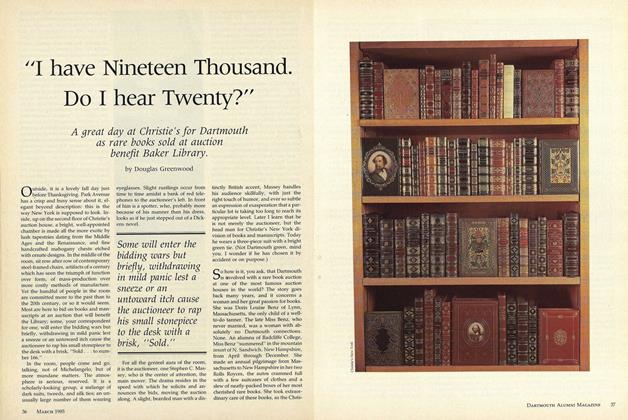

Feature"I have Nineteen Thousand. Do I hear Twenty?"

March 1985 By Douglas Greenwood -

Sports

SportsRecruiters' haul

March 1985 By Jim Kenyan -

Article

ArticleDynamite

March 1985 By Alice Dragoon '86 -

Article

ArticleRandom Thoughts

March 1985 By Gayle Gilman '85