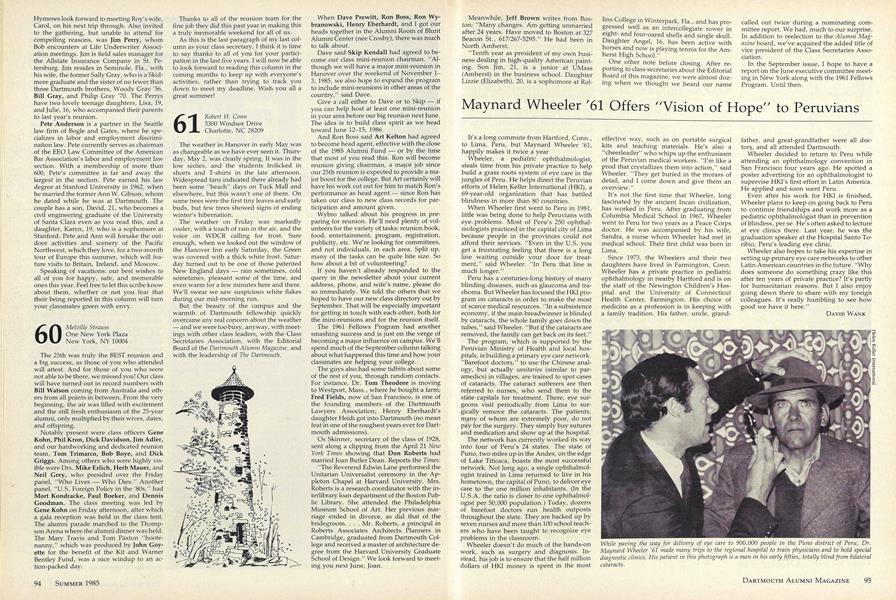

It's a long commute from Hartford, Conn., to Lima, Peru, but Maynard Wheeler '61, happily makes it twice a year

Wheeler, a pediatric ophthalmologist, steals time from his private practice to help build a grass roots system of eye care in the jungles of Peru. He helps direct the Peruvian efforts of Helen Keller International (HKI), a 69-year-old organization that has battled blindness in more than 80 countries.

When Wheeler first went to Peru in 1981, little was being done to help Peruvians with eye-problems. Most of Peru's 250 ophthal- mologists practiced in the capital city of Lima because people in the provinces could not afford their services. "Even in the U.S. you get a frustrating feeling that there is a long line waiting outside your door for treat- ment," said Wheeler. "In Peru that line is much longer."

Peru has a centuries-long history of many blinding diseases, such as glaucoma and trachoma. But Wheeler has focused the HKI program on cataracts in order to make the most of scarce medical resources. "In a subsistence economy, if the main breadwinner is blinded by cataracts, the whole family goes down the tubes," said Wheeler. "But if the cataracts are removed, the family can get back on its feet."

The program, which is supported by the Peruvian Ministry of Health and local hospitals, is building a primary eye care network. "Barefoot doctors," to use the Chinese analogy, but actually sanitarios (similar to paramedics) in villages, are trained to spot cases of cataracts. The cataract sufferers are then referred to nurses, who send them to the state capitals for treatment. There, eye surgeons visit periodically from Lima to surgically remove the cataracts. The patients, many of whom are extremely poor, do not pay for the surgery. They simply buy sutures and medication and show up at the hospital.

The network has currently worked its way into four of Peru's 24 states. The state of Puno, two miles up in the Andes, on the edge of Lake Titicaca, boasts the most successful network. Not long ago, a single ophthalmologist trained in Lima returned to live in his hometown, the capital of Puno, to deliver eye care to the one million inhabitants. (In the U.S.A. the ratio is closer to one ophthalmologist per 50,000 population.) Today, dozens of barefoot doctors run health outposts throughout the state. They are backed up by seven nurses and more than 100 school teachers who have been taught to recognize eye problems in the classroom.

Wheeler doesn't do much of the hands-on work, such as surgery and diagnosis. Instead, his job is to ensure that the half million dollars of HKI money is spent in the most effective way, such as on portable surgical kits and teaching materials. He's also a "cheerleader" who whips up the enthusiasm of the Peruvian medical workers. "I'm like a prod that crystallizes them into action," said Wheeler. "They get buried in the morass of detail, and I come down and give them an overview."

It's not the first time that Wheeler, long fascinated by the ancient Incan civilization, has worked in Peru. After graduating from Columbia Medical School in 1967, Wheeler went to Peru for two years as a Peace Corps doctor. He was accompanied by his wife, Sandra, a nurse whom Wheeler had met in medical school. Their first child was born in Lima.

Since 1973, the Wheelers and their two daughters have lived in Farmington, Conn. Wheeler has a private practice in pediatric ophthalmology in nearby Hartford and is on the staff of the Newington Children's Hospital and the University of Connecticut Health Center, Farmington. His choice of medicine as a profession is in keeping with a family tradition. His father, uncle, grandfather, and great-grandfather were all doctorg, and all attended Dartmouth.

Wheeler decided to return to Peru while attending ah ophthalmology convention in San Francisco four years ago. He spotted a poster advertising for an ophthalmologist to supervise HKI's first effort in Latin America. He applied and soon went Peru.

Even after his work for HKI is finished, Wheeler plans to keep on going back to Peru to continue friendships and work more as a pediatric ophthalmologist than in prevention of blindess, per se. He's often asked to lecture at eye clinics there. Last year, he was the graduation speaker at the Hospital Santo Toribio, Peru's leading eye clinic.

Wheeler also hopes to take his expertise in setting up primary eye care networks to other Latin American countries in the future. "Why does someone do something crazy like this after ten years of private practice? It's partly for humanitarian reasons. But I also enjoy going down there to share with my foreign colleagues. It's really humbling to see how good we have it here."

While paving the way for delivery of eye care to 900,000 people in the Puno district of Peru, Dr.Maynard Wheeler '61 made many trips to the regional hospital to train physicians and to hold specialdiagnostic clinics. His patient in this photograph is a man in his early fifties, totally blind from bilateralcataracts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureA Humanist Ponders the Future of Liberal Education

June 1985 By Charles T. Wood -

Feature

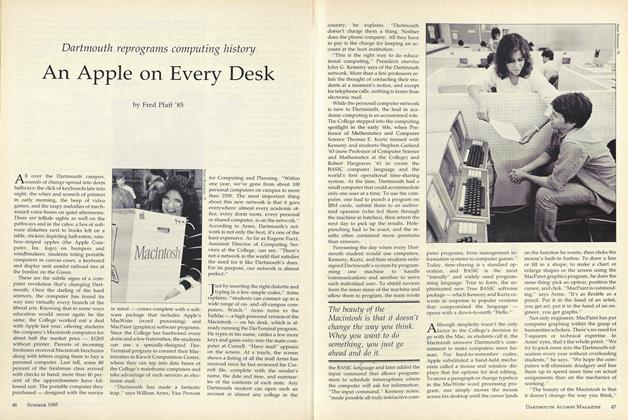

FeatureAn Apple on Every Desk

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

FeatureThe Great Train Robbery

June 1985 By Fred Pfaff '85 -

Feature

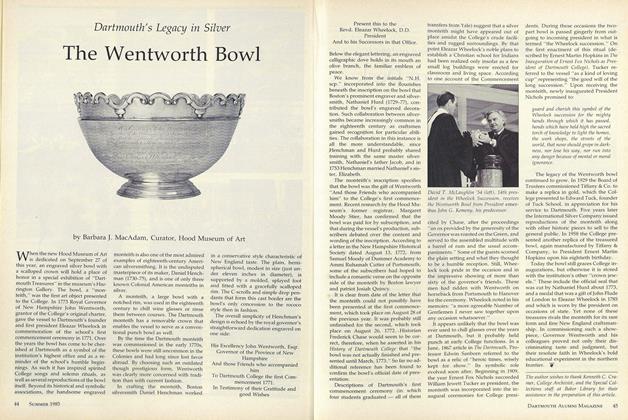

FeatureThe Wentworth Bowl

June 1985 By Barbara J. MacAdam, Curator, Hood Museum of Art -

Cover Story

Cover StoryValedictory Address

June 1985 -

Feature

FeatureReunions 1985

June 1985 By Robert Frost