Recently, I saw, for the third or fourth time, the movie The Way We Were. For me it is more than a first-rate film and a poignant love story. It is a tale of two personalities both halves of the split American consciousness. Hubbell Gardner, the handsome letterman, represents the Gatsbian pursuit of the American dream through material success and its trappings - a yacht, a screenwriter's job, a bungalow in Malibu. However, throughout the movie, Hubbell is haunted by his pursuit, realizing its inherent worthlessness and expressing his doubts in his appropriately Fitzgeraldian novels. He lives like a carefree rich boy, but he thinks like a Puritan poet trying to come to terms with his faith. Just as he is starting to struggle with these opposing forces, Kathie marches into his life. She is an angry young women with a fierce sense of justice and injustice; the incarnation of the American superego which tells us that we are the New Zion, Winthrop's "city upon a hill" with a moral mandate to fight the forces of evil.

Hubbell and Katie think alike in many ways; but what divides them is that, after a point, Hubbell does not live according to his beliefs, while Katie does. That is why she is an idealist. In desperation, Hubbell shouts at Katie, "You take life too seriously. Everything in the world does not happen to you personally!" John Donne reminds us that no man is an island, and that things in the world do happen to each of us personally.

Because Katie relies on ideas and thinks them through to their ultimate implications, she "takes" everything personally. Hubbell knows instinctively that his overreliance on the superficialities of excessive materialism prohibits him from being a true intellectual. He is troubled with the status quo; but, finally, he is unable to transcend it. He cannot be blamed. He finds no encouragement from his environment to be an intellectual. He is seduced by the tennis court/chablis/ high society glamour, and Katie's proddings finally become a nuisance.

A Katie would have an equally difficult time being an intellectual today. The excessive materialism associated with the twenties seems to creep further into the national psyche each moment. One need only look at the ads in magazines and newspapers: a Boston bank declares that it offers special services to its "preferred customers" (i.e., those with more money); a Scotch ad boasts, "If you're good enough to be able to afford our whiskey, you deserve it." Everywhere one perceives the equation of money with success and lack of money with being a "loser."

During times like these, I am grateful that I am an undergraduate in an institution which, I am convinced, provides a superb undergraduate education. However, I am troubled that learning to live the life of the mind is not as important as it should be at Dartmouth. Like the rest of the country, the atmosphere at Dartmouth today too often feels like the corporate fast track. Corporate recruiting is our version of keeping up with the Joneses. I have heard many a person in the dining hall spit out the salaries he's been offered or the prestigious positions she just landed with 27 different Fortune 500 companies. Worse than that, I've seen people ready to jump off of Baker Tower because Proctor and Gamble didn't offer them a job.

It is easy to find evidence of a disdain of intellectualism at Dartmouth. An English major friend of mine was asked - incredibly, by another Dartmouth student what she intended to do with her major after she graduated teach? "In fact, yes," she answered. "Well," came the astonished reply, "how do you plan on making any money that way?" as if that's all that matters. Another friend of mine received a citation for academic excellence his fourth such award. Someone found out about it and said to him, "Well, that's really nice, but I have fun!" - as if my friend, popular and active in campus activities, didn't - as if being an intellectual cut him off from "life" and good times. Like Hubbell Gardner, we are faced with a split between ideas and actions - between what goes on in the classroom and what occurs outside of it. At the beginning of the term, I heard one student say to another, quite seriously, "Oh, yeah, take an art history course. It really gives you something sophisticated to talk about at cocktail parties." This attitude sends a message to Dartmouth intellectuals - faculty and students alike that is about as subtle as a sumo wrestler barreling in for the kill.

I am not suggesting that Dartmouth students don't care about their classes or are not interested in learning. For every student who takes a course to glean material for conversation over Perrier and brie, another takes it because the subject matter and the professor are fascinating. It's just that too often classes are only a part of, instead of the primary part of, the "Dartmouth experience." It's fine that Dartmouth students are well-rounded individuals who participate in extracurricular activities and are concerned with forming lasting friendships. That's one of the reasons I came to Dartmouth. And it's not healthy to be too fully immersed in one's coursework; one needs activities and a social life, too. But we place so much emphasis on being well-rounded that we forget about the education that we came to Dartmouth to receive. Admittedly, what occurs outside of the classroom contributes to our education; but the heart of learning is found in those hours we spend writing, reading, and thinking, and in the professor/student relationship.

At Dartmouth, we have a faculty committed to the education of students, yet very few of those students go to faculty office hours to become better acquainted with the professor and the subject matter. In many ways, one cannot blame students. The messages they receive from contemporary American society and even from Dartmouth itself undercut the value of a liberal arts education. Fearing their education is not "practical," many students make themselves more attractive to the business world by desperately filling their Dartmouth career with economics courses or "prestige" leave term jobs. Because it is not "practical" or "cool" to be an intellectual, many eschew the appearance of taking their classes "too seriously." At a recent party, someone with a significant affiliation to Dartmouth commented, "It is not the mission of Dartmouth to be an intellectual institution." I disagree. To nurture the life of the mind and to assure that education is an end in itself - not just a means to an end-is the central mission of an educational institution. Dartmouth has no responsibility to perpetuate the institution; it has a powerful mandate to perpetuate education and an intellectual community.

George Santayana wrote of "the omnipotence of imaginative thought: its power first to make the world, then to understand it, and finally to rise above it." Likewise, Dartmouth should respond to the times, it should understand them; but it should rise above them. It must respond to the times with this principle alone as its touchstone: that each human being must create, through the pursuit of ideas, his or her own existence and should live according to his or her ideas - should live, in effect, the life of the mind. Especially at a college, there must never be a stigma attached to those who try to do this. Dartmouth, like Katie, should transcend the materialism of the times and insist that the quality of intellectual pursuit is the only tradition that must never fail and the only tradition that should not be subject to question.

The business of America might be business; but the business of Dartmouth is education. Stealing a dictum of American materialism, Dartmouth should put its money where its mouth is. We speak here in Hanover about the importance of the liberal arts and the pursuit of academic excellence. I like to think that it's a vision, not just rhetoric. To support our scholars we must do two things. First, we must support the teachers, those who instruct us with such excellence and style how to live the life of the mind. We must make sure that they do not leave Dartmouth because of financial considerations or a milieu inimical to teaching and learning. Secondly, the overt and tacit atmosphere of the College must encourage all students to understand that they are at Dartmouth to have four fulfilling years. Above all they are here to think, to look deeply at a Rembrandt, to perceive the poetry in the words of Emerson, Keats, or Millay, and perhaps even to discover that Virginia Woolf can be more interesting and important than T. Boone Pickens.

"Dottie" Foley is a senior from Swampscott,Mass. One of the Magazine's two WhitneyCampbell interns, she is majoring in English.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom "a few curious Elephants Bones" to Picasso

September 1985 By Jacquelynn Baas -

Feature

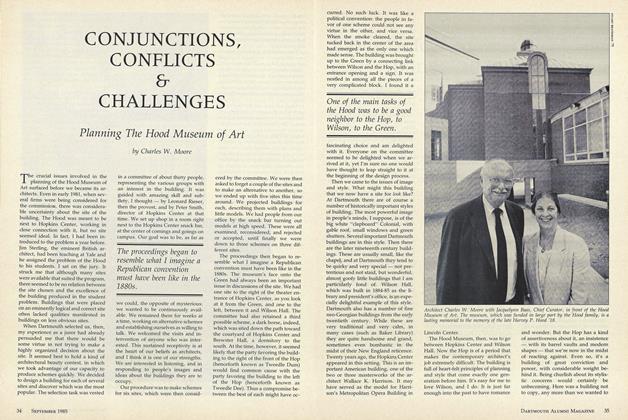

FeatureCONJUNCTIONS, CONFLICTS & CHALLENGES

September 1985 By Charles W. Moore -

Feature

FeatureJourney's End: The Assyrian Reliefs at Dartmouth

September 1985 By Judith Lerner -

Feature

FeatureDingwall of Dartmouth

September 1985 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

September 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsMany Sighs and Many Tears

September 1985 By Jim Kenyon