On February.17, 1853, Prof. Oliver Payson Hubbard, librarian at Dartmouth College, wrote to Dr. Austin Hazen Wright, Class of 1830, a missionary living in northwestern Persia:

Can you without too great trouble to yourself or them persuade some of your brother missionaries at Mosul to procure for your Alma Mater some momentoes of the Ancient Cities now opened on the Tigris? Williams College has, from some of her graduates, received some.

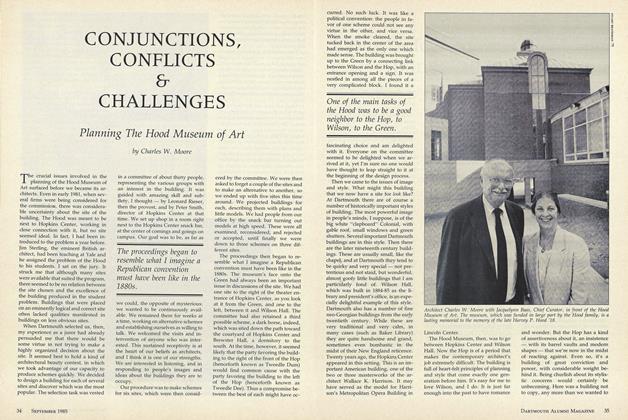

Thus began the negotiations which resulted in Dartmouth acquiring six Assyrian reliefs, now installed in the Hood Museum of Art. The reliefs were acknowledged at the time of their acquisition as the finest of all the bas reliefs sent home by American missionaries in Mosul, and second only to those sent to the British Museum. Today, recently cleaned and restored, the reliefs are among the finest in overall form and detail that have come from the ancient Assyrian capital of Nimrud.

In the 1840s, the French and British began excavation of large mounds in northern Mesopotamia (present day Iraq), which tradition held were the ruined capitals of the great Assyrian Empire (c. 1000-612 B.C.). The Englishman Austen Henry Layard had begun digging in 1845 at Nimrud, the ninth-century capital of the Assyrian king Ashurnasirpal II (883-859 B.C.). In what became known as the Northwest Palace, Layard unearthed colossal sculptures of human-headed bulls which guarded the doorways of the ceremonial parts of the palace and large carved slabs. In decorating the rooms of his palace, Ashurnasirpal continued the long tradition in both northern (Assyria) and southern (Babylonia) Mesopotamia of embellishing the walls with figural compositions and decorative patterns, either painted on wall plaster or composed of bricks molded in relief. Carved with largerthan-life-size figures in low relief, the limestone reliefs record some of the important events in Ashurnasirpal's reign, glorifying him as the "potent king, the king of the world, the king of Assyria."

Across the middle of the limestone slabs is a band, inscribed with the wedge-shaped cunie form signs of the Assyrian language. In the inscription, Ashurnasirpal proclaims his greatness, his role as priest and ruler chosen by the gods, his royal lineage, his invin- cibility, his military exploits, his building of the city of Kalhu, and his founding of what came to be known as the Northwest Palace.

Until the middle of the nineteenth century, the accounts of the Greek historians and the Bible provided our only knowledge of the Assyrians. The discovery of the capital cities of the Assyrians, the people who led into exile the ten tribes of the northern kingdom of Israel, had enormous impact on people in the middle of the nineteenth century; indeed, the Assyrian finds were seen as directly illustrating the Word of God. Nimrud was biblical Calah (Gen. 10:11) - its discovery proof of biblical history. And Dartmouth, like many American colleges in the nineteenth century, had a vested interest in the roots of biblical history and exigesis.

In other quarters, international prestige depended upon the acquisition of Assyrian sculpture as the British and French, and later the Americans, vied with each other for permission from the local Turkish governor to excavate the mounds and be the first to put the treasures on display. The Rev. Dwight Marsh, who, in 1850 had opened a mission station in Mosul, suggested to La- yard that some American colleges would be grateful for examples of the Assyrian reliefs. Layard enthusiastically obliged and offered Marsh two relief slabs from Nimrud to dispose of as he thought best. Marsh immediately sent them to his alma mater, Williams College, where they arrived in 1851.

News of the reliefs at Williams aroused interest at Amherst College and a number of other American colleges, including Dartmouth. According to the late John B. Stearns '16, professor of classics at Dartmouth.from 1927 to 1961, and author of scholarly works on Nimrud reliefs in American collections, between 1852 and 1860 American missionaries in Mosul sent back at least 55 figural slabs from the Northwest Palace at Nimrud.

The removal and transportation of the reliefs was a complex affair. To make them lighter, the slabs were reduced from a foot or more in thickness to only a few inches, and then cut into sections. To make them lighter still, they were cut horizontally into three sections, each wrapped in half-inch thick felt, boxed, wrapped again in felt, and finally secured with rope. They were then transported across the Syrian desert by camel caravan to Alexandretta or Beirut and by ship to the United States. Originally the missionaries had wanted to send them by way of the Persian Gulf and around the Cape of Good Hope to avoid cutting the slabs into so many pieces. But in 1854, a raft containing reliefs from another Assyrian capital, Nineweh, sunk in the Tigris on its way to the port of Basrah; today, more than 130 years later, the sculptures have yet to be recovered. It seemed wiser to brave the vicissitudes of desert travel with the threat of marauding Bedouins than chance a raft journey down the Tigris. Thus when the Dartmouth reliefs did arrive, they were like all the other Assyrian reliefs in the United States, that is, in a number of pieces.

The Mosul missionaries were about to acquire their next consignment of reliefs when Dr. Wright received Prof. Hubbard's request for "some momentoes of the Ancient Cities" for Dartmouth. In June, 1853, Wright asked Richard Stevens, the British Consul at Tabriz, to intercede with Col. Rawlinson, the British Resident in Baghdad, who, after Layard's departure in 1851, had taken over control of British excavations in northern Mesopotamia. Rawlinson kindly obliged, giving 18 re- liefs to the American missionaries, with six of them assigned to Dartmouth.

This caused some consternation in Mosul. Not only were the missionaries competing for as many reliefs as Rawlinson would allow them, they were after as many different kinds of figures as were available. Rev. Marsh complained in a letter, "As Dartmouth had first choice, that college has a fine collection and little more than duplicates were left for us." Royal images were especially desired, but they were scarce. Most common were figures of winged genie and sacred trees. As luck would have it, Dartmouth was granted a nearly complete range of figural types that occur in these ceremonial reliefs: the figure of Ashurnasirpal himself; one of his attendants, winged genies - one accompanying the king, one with a pail and a date palmspathe, another annointing a sacred tree with a date palm-spathe, a fourth holding only a pail, and, finally, a wingless genie, also holding a pail. The only figural type that is lacking is the winged genie with a griffin-head. Dr. Lobdell congratulated Wright for his "determination to keep the whole [lot] of them. I would deny myself a good deal to send such a set to Amherst."

Apparently Wright never saw the reliefs, but merely acted on the request from his alma mater. How, nearly 200 miles from Nimrud, was he able to secure what Lobdell declared was "the best yet sent over the Atlantic" when the Mosul misisonaries were living just 20 miles north of the site is something of a wonder itself. Clearly, Wright had the inside track in securing Col. Rawlinson's cooperation

It was Rawlinson's hard work that led to his decipherment of the Old Persian cuneiform signs, and, by 1849, the decipherment of the Assyrian script. Rawlinson's accomplishment, similar to Champollion's decipherment of the Rosetta Stone (and thus Egyptian hieroglyphics), enabled scholars to read the Assyrian and Babylonian cunei-form texts, which, from the middle of the nineteenth century, were being unearthed with increasing frequency. Unfortunately, Lobdell died of typhus before he could finish packing the reliefs for Dartmouth. But the work was carried on faithfully by Marsh who assurred Wright in the summer of 1855:

Not a little care has been spent on these slabs by the native workmen and in superintending them by our lamented brother Lobdell and by Mr. Williams and myself. They have the gauntlet of the desert to run, and the Ocean may molest them with its storms, but we hope that more successful than Ledyard, they may find their way to that College which saw the adventurer embark down the Connecticut in a canoe.

The reliefs finally arrived in Hanover on December 11, 1856. At the Dartmouth commencement in 1857, Rawlinson received the degree of LL.D. Some two years later, he gratefully acknowledged his honorary degree:

Amid the many honors I have received from literary bodies interested in Oriental science, there is none which I value more than the diploma which the University of Dartmouth [sic] has been pleased to confer upon me.

Thus, through the efforts of a Dartmouth professor and an alumnus, Dartmouth acquired "the most valuable set of [Assyrian] sculptures yet sent to America."

Judith Lerner, who has taught at SmithCollege and in Iran, received her Ph. D. inancient art from Harvard University.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

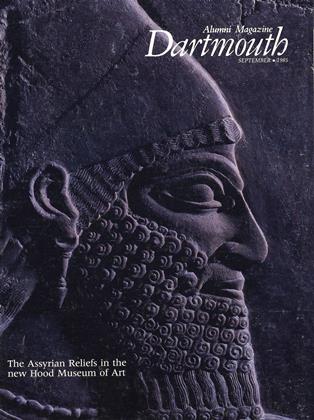

FeatureFrom "a few curious Elephants Bones" to Picasso

September 1985 By Jacquelynn Baas -

Feature

FeatureCONJUNCTIONS, CONFLICTS & CHALLENGES

September 1985 By Charles W. Moore -

Feature

FeatureDingwall of Dartmouth

September 1985 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryBack on the Wall (where they belong)

September 1985 By Georgia Croft -

Sports

SportsMany Sighs and Many Tears

September 1985 By Jim Kenyon -

Article

ArticleThe Life of the Mind

September 1985 By Dorothy Foley '86

Features

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Ledyard 1776

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

FeatureThe Case of the Prodigal Son

MARCH • 1986 By Bruce Ducker '60 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

Sept/Oct 2008 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Cover Story

Cover StoryLoyalty's Roots

APRIL 1989 By Katie Crane -

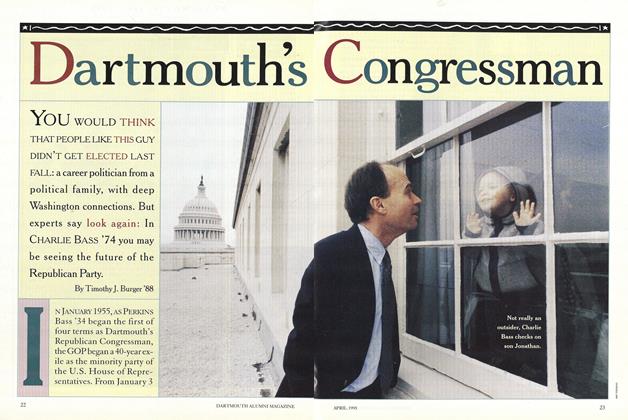

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth's Congressman

April 1995 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

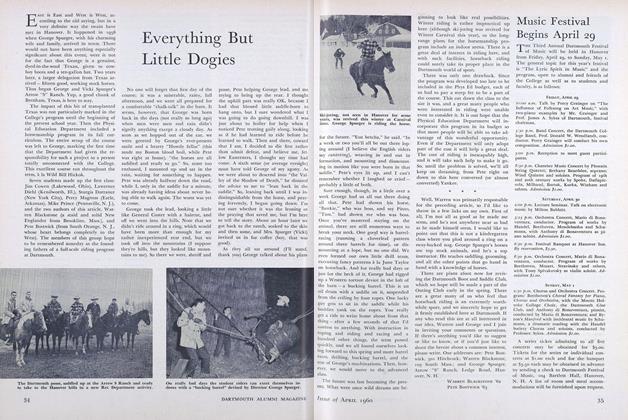

FeatureEverything But Little Dogies

April 1960 By WARREN BLACKSTONE '62, PETE BOSTWICK '63