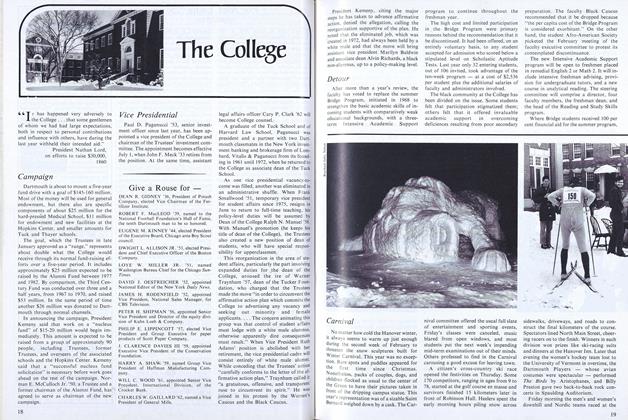

After spending several mornings at my three-year-old's playgroup run by the YWCA at a downtown Minneapolis church, I was surprised how much I enjoyed it. Initially, the thought of being locked in a room with 15 two- and three year-olds seemed a poor substitute to cafeau lait at one of my favorite morning hangouts.

My wife, Susie, and I had a precedent for such paternal participation. We had shared most experiences relating to Bria, our three-year-old. We had gone together to Susie's prenatal visits; we had struggled through a 36-hour labor together; and when the time came for well-baby care, I could conveniently drop over to Bria's doctor, who practiced across the hall from my own office. Together we discussed the milestones of our daughter's development and even worked through some of the frustrations related to three strong-willed creatures living under the same roof.

Becoming a father at 38 permitted me a different freedom than if I had undergone the rite de passage of early fatherhood in my twenties as most of my contemporaries from Hanover probably did. While I was a medical student or medical resident there was no way to casually tell the chief of staff or a professor, "Cancel everything for next Tuesday morning; I'm going to playschool with my daughter."

Bria's teacher, Mary Maclaughlin, enthusiastically helped alter my attitude about my parental obligation of spending one morning a quarter at Bria's playgroup. In fact, I found myself volunteering in Susie's place when there was a need to fulfill our family's quota.

Mary and my new little friends welcomed everyone into the group as they sat in a circle patting their knees and singing. The kids were aware of each other's presence and happily made eye contact, giggled, and welcomed "big people" into their circle.

The time at playgroup was about as structured a program as most two- or three-year-olds could tolerate. As our morning began, I watched Bria and one or another of her friends jockeying for position with the paints. (Usually, this converted the clean pastel shirt some unsuspecting mother had chosen for her loved one into a multicolored variety.)

The children could lose themselves while fingerpainting with shaving cream. This allowed them to feel textures, and the cream was both harmless and effortlessly removed. Several would stand by the low sink and watch the foam go down the drain before taking off to their next challenge of the morning. I was astounded by their energy and usually followed along, exhausted.

After some singing and cleaning up, the children left these activities for another room with bigger play settings and slides, kitchen sets, hideouts, basketballs, and hoops. It was here I watched my daughter and her buddy Melissa fall over laughing after one of them had accidentally missed a seat she was aiming for. What I saw was elementary slapstick, children totally uninhibited, not taking themselves too seriously. They enjoyed the joke so much that they laughed hysterically and improvised the pratfall over and over.

I felt a bit like Margaret Mead among the Polynesians. Suddenly, I was back in Anthropology I among the natives. "Refreshing," I thought; "sure beats internal medicine."

"They really do understand what I'm saying," I thought. From these sessions I began to learn to communicate better with my own child as well as other children. I watched as they portrayed the gamut of emotions: the happy or shy child, the sad child, the child who would watch me fearfully and then retreat into Mary's arms. An otherwise silent child would suddenly be in my lap as I read a story to another. Suddenly I was the surrogate parent for one who was in Boston on a business trip. Merely by changing the diaper on an apprehensive child raw with eczema made me appreciate how lucky I was that my own child was healthy.

A sense of caring was so much a part of playgroups. On the last morning of the school year, I happily grabbed Bria and her friend Tracy by the hand as they held each other. As I began to twirl them both around I heard a "crack" from Bria's arm as she froze in discomfort. She immediately tucked her arm against her body and began crying. Her little friends were noticably affected, and chatter disappeared. Elizabeth, Mary's assistant, cradled Bria while I called her physician. "Housemaid's elbow," he said, matter-offactly. He reassured me he could easily reduce what was a fairly common dislocation if I brought Bria over to the office. When I returned from the phone, Bria was peacefully asleep, still protecting her elbow with her other arm. This experience brought me closer to Bria and her little friends as I understood their early caring for one another.

At first I had joked when Susie arranged for us to attend the twice-a-year conferences with Bria's teachers. Once there, however, we would learn about Bria's good qualities, why she was special, and how she interacted with other adults and her first classmates. This feedback was so helpful in appreciating our daughter all the more. I was surprised how easy it felt to bounce questions off Mary about child-rearing and sometimes even related marital stresses. I suspect such preschool play periods nurtured my daughter's self-esteem and her techniques of relating to other children.

Participating as I did in my daughter's playgroups allowed me to "play" again, just as I learned how to interact better with my own child and others. These visits made me feel better about my role as father and parent: as Dad.

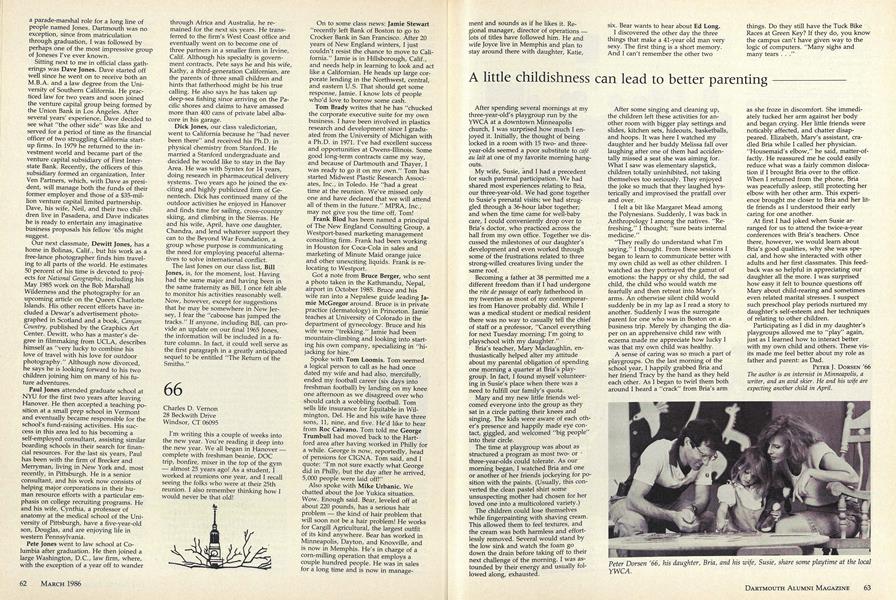

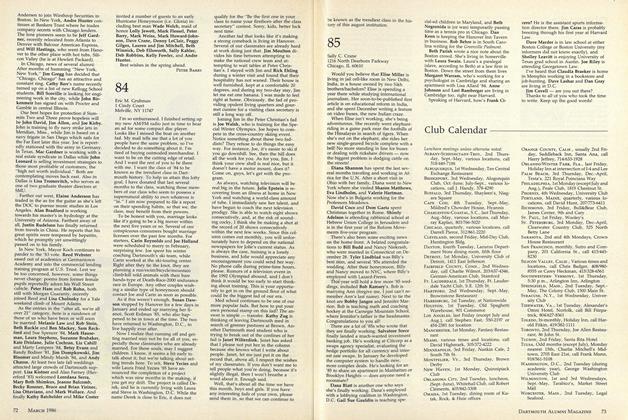

Peter Dorsen '66, his daughter, Bria, and his wife, Susie, share some playtime at the localYWCA.

The author is an internist in Minneapolis, awriter, and an avid skier. He and his wife areexpecting another child in April.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

Feature"Dear Folks..."

March 1986 By H. Nicholas Muller III '60 -

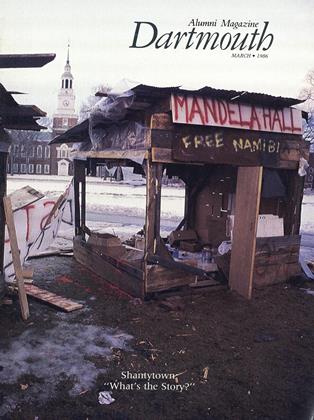

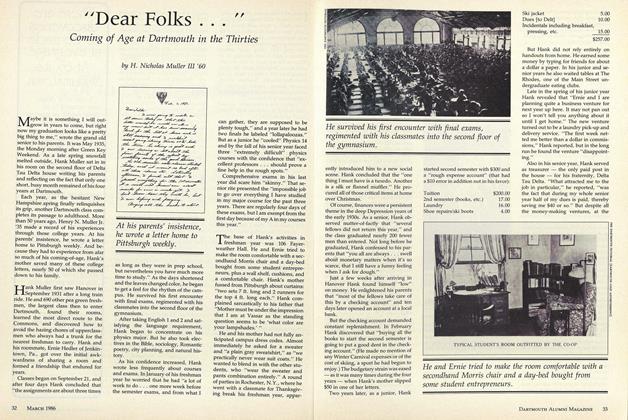

Cover Story

Cover StoryShanty town "What's the story?"

March 1986 By Peter Mandel and Doug Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeatureThe Case of the Prodigal Son

March 1986 By Bruce Ducker '60 -

Article

ArticleMatthew Marshall: Keeper of the Inn

March 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleFaculty governance report is released

March 1986 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

March 1986 By Eric M. Grubman