Coming of Age at Dartmouth in the Thirties

Maybe it is something I will outgrow in years to come, but right now my graduation looks like a pretty big thing to me," wrote the grand old senior to his parents. It was May 1935, the Monday morning after Green Key Weekend. As a late spring snowfall melted outside, Hank Muller sat in in his room on the second floor of Delta Tau Delta house writing his parents and reflecting on the fact that only one short, busy month remained of his four years at Dartmouth.

Each year, as the hesitant New Hampshire spring finally relinquishes its grip, another Dartmouth class completes its passage to adulthood. More than 50 years ago, Henry N. Muller Jr. '35 made a record of his experiences through those college years. At his parents' insistence, he wrote a letter home to Pittsburgh weekly. And because they had to experience from afar so much of his coming-of-age, Hank's mother saved many of these college letters, nearly 50 of which she passed down to his family.

Hank Muller first saw Hanover in September 1931 after a long train ride. He and 690 other pea green freshmen, the largest class then to enter Dartmouth, found their rooms, learned the most direct route to the Commons, and discovered how to avoid the hazing chores of upperclassmen who always had a trunk for the nearest freshman to carry. Hank and his roommate, Ernie Hedler of Jenkintown, Pa., got over the initial awkwardness of sharing a room and formed a friendship that endured for years.

Classes began on September 21, and after four days Hank concluded that "the assignments are about three times as long as they were in prep school, but nevertheless you have much more time to study." As the days shortened and the leaves changed color, he began to get a feel for the rhythm of the campus. He survived his first encounter with final exams, regimented with his classmates into the second floor of the gymnasium.

After taking English 1 and 2 and satisfying the language requirement, Hank began to concentrate on his physics major. But he also took electives in the Bible, sociology, Romantic poetry, city planning, and natural history.

As his confidence increased, Hank wrote less frequently about courses and exams. In January of his freshman year he worried that he had "a lot of work to do . . . one more week before the semester exams, and from what I can gather, they are supposed to be plenty tough," and a year later he had two finals he labeled "lollapaloozas." But as a junior he "cooled" Physics 14 and by the fall of his senior year faced three "extremely difficult" physics courses with the confidence that "excellent professors . . . should prove a fine help in the rough spots."

Comprehensive exams in his last year did scare him "skinny." That senior rite presented the "impossible job to go over everything I have studied in my major course for the past three years. There are regularly four days of these exams, but I am exempt from the first day because of my A in my courses this year."

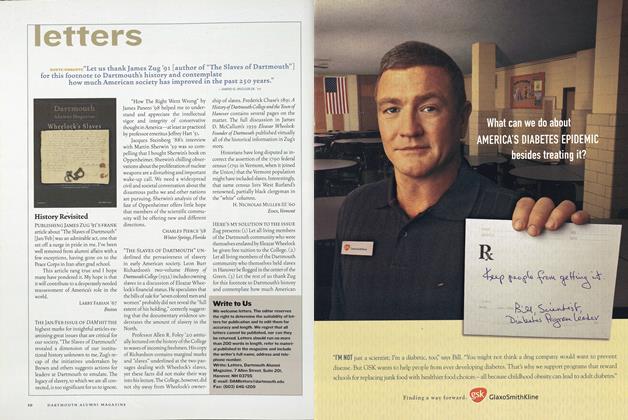

The base of Hank's activities in freshman year was 106 Fayerweather Hall. He and Ernie tried to make the room comfortable with a secondhand Morris chair and a day-bed bought from some student entrepreneurs, plus a wall shelf, cushions, and a comfortable chair. Hank's mother fussed from Pittsburgh about curtains: "two sets 7 ft. long and 2 runners for the top 4 ft. long each." Hank complained sarcastically to his father that Mother must be under the impression that I am at Vassar as the standing question seems to be 'what color are your lampshades.'"

He and his mother had not fully anticipated campus dress codes. Almost immediately he asked for a sweater and "a plain gray sweatshirt," as "we practically never wear suit coats." He wanted to blend in with the other students, who "wear the sweater and pants combination entirely." A round of parties in Rochester, N.Y., where he went with a classmate for Thanksgiving break his freshman year, apparently introduced him to a new social scene. Hank concluded that the"one thing I must have is a tuxedo. Another is a silk or flannel muffler." He procured all of those critical items at home over Christmas.

Of course, finances were a persistent theme in the deep Depression years of the early 19305. As a senior, Hank observed matter-of-factly that "several fellows did not return this year," and the class graduated nearly 200 fewer men than entered. Not long before he graduated, Hank confessed to his parents that "you all are always . . . swell about monetary matters when it's so scarce, that I still have a funny feeling when I ask for dough."

Just a few weeks after arriving in Hanover Hank found himself "low" on money. He enlightened his parents that "most of the fellows take care of this by a checking account" and ten days later opened an account at a local bank.

But the checking account demanded constant replenishment. In February Hank discovered that "buying all the books to start the second semester is going to put a good dent in the checking account." (He made no mention of any Winter Carnival expenses or of the cost of skiing, a sport he had begun to enjoy.) The budgetary strain was eased- as it was many times during the four years-when Hank's mother slipped $5O in one of her letters.

Two years later, as a junior, Hank started second semester with $300 and a "rough expense account" (that had a $10 error in addition not in his favor):

Tuition $200.00 2nd semester (books, etc.) 17.00 Laundry 16.00 Shoe repairs/ski boots 4.00 Ski jacket 5.00 Dues [to Delt] 10.00 Incidentals including breakfast, pressing, etc. 15.00 $257.00

But Hank did not rely entirely on handouts from home. He earned some money by typing for friends for about a dollar a paper. In his junior and senior years he also waited tables at The Rhodes, one of the Main Street undergraduate eating clubs.

Late in the spring of his junior year Hank revealed that "Ernie and I are planning quite a business venture for next year up here. It may not pan out so I won't tell you anything about it until I get home." The new venture turned out to be a laundry pick-up and delivery service. "The first week netted me better than a dollar in commissions," Hank reported, but in the long run he found the venture "disappointing."

Also in his senior year, Hank served as treasurer-the only paid post in the house-for his fraternity, Delta Tau Delta. "What attracted me to the job in particular," he reported, "was the fact that during my whole senior year half of my dues is paid, thereby saving me $40 or so." But despite all the money-making ventures, at the end of his senior year, when "most of the senior class went on a toot to celebrate the end of exams," Hank did not join in because he had "too much to do" and, even more to the point, was "pretty broke."

Fraternities became part of Ernie and Hank's experience when they returned to Hanover from their first Christmas vacation. The fraternities prepared for formal rush by inviting freshmen to attend "informal" teas and lectures. On January 9, 1932, Hank and Ernie received "invitations to the Theta Chi fraternity for an informal tomorrow afternoon. I don't think I know any Theta Chi's, but I probably do and just don't know it." Alpha Sigma Phi invited him to an informal where a professor spoke. During the spring, Delta Upsilon, Theta Delta Chi, Alpha Delta Phi, and Delta Tau Delta all issued similar invitations.

While the campus went through the annual turmoil of working out rooming arrangements for the next year, Hank and Ernie apparently cut a deal with Delta Tau Delta. "We are not keeping [106] for next year," Hank wrote his parents, "as we got what we consider a most wonderful break on our part. We are going to room in the Delt house. There are no sophomores rooming in fraternity houses this year, and I think we will be the only ones next year. . . The rooms aren't so large as the one that we have now, but over there your room is just used for sleeping and studying, while here it is our house." In case his parents had any reservations, he pointed out that the Delt room would cost $70 less-a happy estimate which ignored fraternity dues.

The sagacious sophomore and proud new resident of Delt house returned to campus in September 1932 full of confidence. Hank became active in the rushing process and by the end of the first week of classes thought "our delegation here at the house for the class of '35 is coming along great. We have 12 fine fellows and are practically sure of getting 5 to 7 more." It was a busy time: "Study all afternoon, go rushing all evening, and classes all morning, phew!"

Pledge night brought apparent success to the Delts, and the rites of initiation began. "You should have seen me carving my initials in every step of the ski jump. It was some job, I gouged away all afternoon. As a result there is an HM in every one of the 200 steps."

The pledges also joined the organized mayhem of intramural football, played in the lengthening shadows of fall afternoons on the Green. Without pads or training, exuberant students often received more injuries than the varsity. Hank wrote home one week about a "severe" concussion he received in a Green skirmish. "I was running for a pass while playing on the Delt football team, and slipped and got kicked in the head. I was out for about 20 minutes, and when they brought me to, my mind wouldn't seem to work." The doctors interned Hank briefly in Dick's House but shortly pronounced "everything jake." The resulting bill for $15.51 was not so jake, and Hank determined to escape it. "I am going to use my best salesmanship," he promised, "to see if I can get it taken off as I was injured while engaging in intramural athletics."

In winter, intramurals moved into the gym, the hockey rink, and the swimming pool. Hank swam the 50- yard freestyle but most enjoyed baseball when the advent of spring brought intramurals back to the Green. In 1934 the Delt nine finished in second place. In the final game of the brief season, "in the first inning with one on base, I met one square on the schnozzola and sent it clear out of the park and into the library front lawn for an easy home run." Later that spring, the "allfraternity" team beat the undefeated Dartmouth freshmen 18-3, and Hank enjoyed a two-hit afternoon, including a triple.

Much of the upperclassmen's social life centered on the fraternity. Not long after pledging, Hank made the first of many five-hour drives down tortuous Route 5 to Smith College. After classes one Saturday morning early in 1933, "about 1 p.m., one of the fellows said, 'Hey guys, let's go to Hamp.' Sooo six of us piled in his car (a big Buick Phaeton) and by six thirty we were in Northampton. We got something to eat, went to a dance," and spent the night at the Delt lodge at Amherst.

The fraternity parties in Hanover ran the full range from those with formal invitations and chaperones to spur-of-the-moment affairs. At least one Delt party in the fall of 1932 incurred the disapproval of the administration. President Hopkins eventually "settled the mess we got into house parties, and as a result "we don't have anycarnival." Later that fall, Hank and five friends who stayed in Hanover over Thanksgiving break "got permission from Hopkins and held a party here at the house. I'd like to see them complain this time for among the guests were the president's daughter, both dean's daughters and several other faculty members." During that break they also drove to Canada one day, where they "all had a bottle of real Canadian Ale."

Hank and his friends also learned how to enliven a party in Hanover. On one occasion, he and Ernie spent $8.00 on a gallon of alcohol from the Norwich bootlegger, Joe Pities. "That, plus juniper flavoring from the drugstore, made more than two gallons of gin (shaken well and aged three minutes)," Ernie recalled recently. "Mixed half and half with grapefruit juice, it made a passable drink." Hank and Ernie censored that experience from their letters home, however.

In May 1933, at the end of his sophomore year, Hank and his friends no longer had to drive to Canada to quaff legal beer. Repeal came to Hanover, and local merchants took over from the bootleggers. On May 28, 1933, he informed his mother that "beer is here in Hanover, and has been for the last week, but so far," he claimed, "I have had only one bottle. They want 20 cents per bottle, and that's too much for me, so I'll stay on the water wagon." He thought the advent of legal beer made a noticeable difference on campus. "Although 6 percent beer is the only change up here after repeal, the boys seem to be enjoying it to its utmost." He reported lots of "good college spirit expressed in a restaurant full of just slightly mellowed students," and said that beer also enlivened pledge night. On pledge night in the fall of 1934 he "witnessed the worst schutzenfest I ever hope to see. Everybody in the school seemed to go on a tear and Ernie and myself and a few others had a heck of a time trying to keep the general mob from wrecking the house."

Fall football weekends offered another outlet for undergraduate gusto. From the Friday night rallies on the Green to the post-victory bell-tailings in Rollins Chapel, high spirits surrounded every Saturday contest.

Hank followed most varsity sports, but he held football paramount. Each fall from 1931 through 1934 the bright hopes of September dropped with the leaves. In those four seasons the teams finished 5-3-1, 4-4-0, 4-4-1, and 6-3-0, usually rolling over the early part of the schedule before running up against tough Ivy rivals, and campus morale rode the roller coaster of the team's success. On the basis of convincing wins over Norwich, Buffalo, and Holy Cross-"relatively minor opposition," according to the Aegis-the freshman pundit in 106 Fayerweather predicted that Dartmouth stood "a pretty good chance with Yale, Columbia, Stanford, Harvard, etc." The team disappointed him, tying Yale and losing the other three.

The next season opened the same way, and after a 14-7 loss in the fourth game to Penn, Hank expected that "Harvard is going to give us some walloping next week." Dartmouth fell to the Crimson in a close game and managed only one more win. Hank saw how "a little thing like a football game cart put 2000 fellows in a bad humor."

The campus returned for the 1933 season with renewed optimism, but the same pattern was repeated. Hank and his friends followed coach Jack Cannell and the team to Harvard to watch a last-minute 7-7 tie which Hank pronounced "some thriller." With a minute to play, Bill Clark ran 55 yards for a touchdown, and left tackle Don Hagerman kicked the tying point. Hank "never saw 40,000 people act so much like maniacs before. . . They tore up the goal posts, knocked down the police, and tear gas had no effect." But the heroic tie at Harvard did not fool Hank, now an experienced junior. He returned to Hanover certain "our undefeated team is going to take it on the 'button' next week," and it lost the last four games.

In Hank's senior year Earl "Red" Blaik began his successful tenure as coach. The team, decked out in "swanky" new uniforms of silver satin pants and green jerseys, won the first five games, including a 10-0 victory at Harvard for which "the College [had] migrated en masse to Boston." At last that season "the Dartmouth constituency that was hoarse as a crow from so many years singing in the rain, may be hoarse now from another and more satisfying reason." When the team dropped a hard-fought contest to Yale, ending the winning streak, the students "were not at all upset, as the whole ball club is laid up with injuries and besides after the Yale game the peak of the season has been reached, and the rest is always an anti-climax."

By the time of the Yale Bowl debacle, Hank had begun to look beyond football. One winter road trip the year before had left for "Hamp" but encountered impassable roads and detoured to Colby Junior College. There Hank had met Harriet Kerschner, and quickly the focus of his social life shifted from Northampton, Mass., to New London, N.H. He invited Harriet for Winter Carnival in 1934, "as she is a lot of fun and is sure to go good with the rest of the gang."

Preparing to leave Hanover after finals in June 1934, Hank warned his parents, "You had better brace yourself for here comes the break." He prepared to visit Harriet and her parents in New Jersey on his way home but worried that he was "assuming too much liberty by planning such things without first consulting the strong hand of the law at home."

Harriet also visited Hank in Pittsburgh, and the bond between them deepened when they returned to New Hampshire in September for their last year of college. After the Colby Junior prom, where he had "a swell time," Hank told his parents that "the more times I see that girl in a large crowd, the more I realize how she stands out among others. I am very proud of her, am envied by the whole fraternity here, and I love her very much."

By the time Harriet joined Hank's parents in Hanover for Commencement, Hartk was looking ahead to marriage and his first job but also realized how much he was "going to hate to leave the place, its associations, and its good times."

At his parents' insistence,he wrote a letter home toPittsburgh weekly.

He survived his first encounter with final exams,regimented with his classmates into the second floor ofthe gymnasium.

TYPICAL STUDENTS ROOM OUTFITTED BY THE CO-OP

Hank saw how "a littlething like a football gamecan put 2000 fellows in abad humor."

Hank was looking ahead tomarriage and his first jobbut also realized howmuch he was "going tohate to leave the place, itsassociations, and its goodtimes."

He and Ernie tried to make the room comfortable with asecondhand Morris chair and a day-bed bought fromsome student entrepreneurs.

The author, one of the late Hank Muller'stwo sons who followed him at Dartmouth,holds a Ph.D. in history from the University of Rochester. He was president of hismother's alma mater, now Colby SawyerCollege, from 1978 to 1985, and he is currently director of the State Historical Society of Wisconsin.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

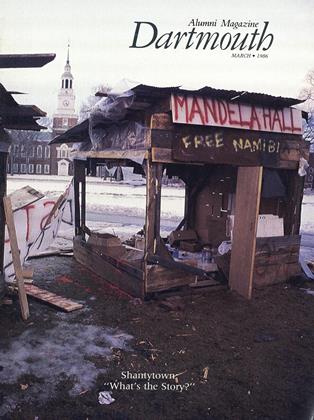

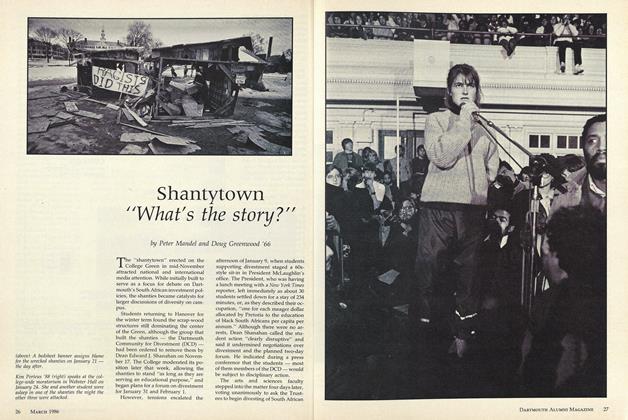

Cover StoryShanty town "What's the story?"

March 1986 By Peter Mandel and Doug Greenwood '66 -

Feature

FeatureThe Case of the Prodigal Son

March 1986 By Bruce Ducker '60 -

Article

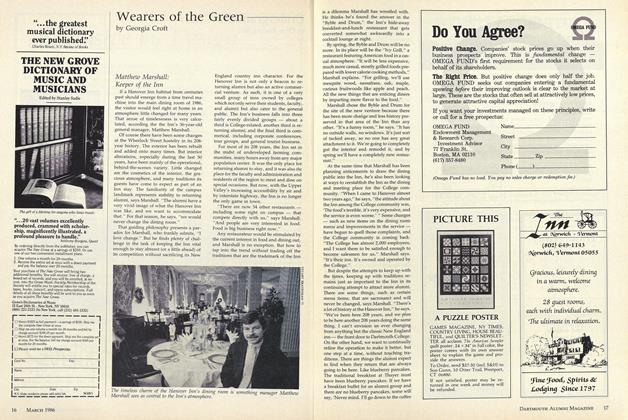

ArticleMatthew Marshall: Keeper of the Inn

March 1986 By Georgia Croft -

Article

ArticleFaculty governance report is released

March 1986 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1984

March 1986 By Eric M. Grubman -

Article

ArticleA little childishness can lead to better parenting

March 1986 By Peter J. Dorsen '66

H. Nicholas Muller III '60

Features

-

Feature

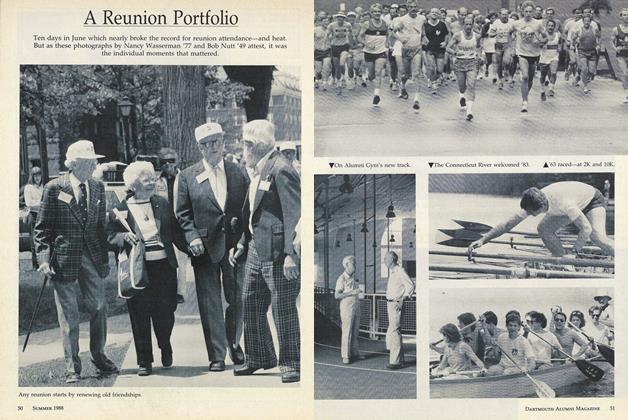

FeatureA Reunion Portfolio

June • 1988 -

Feature

FeatureMISGUIDED

Nov/Dec 2000 -

Feature

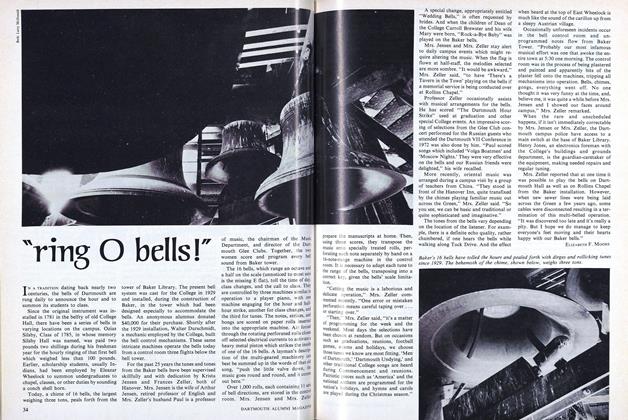

Feature"ring O bells!"

November 1974 By ELIZABETH F. MOORE -

Feature

FeatureThe 190th Commencement

JULY 1959 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

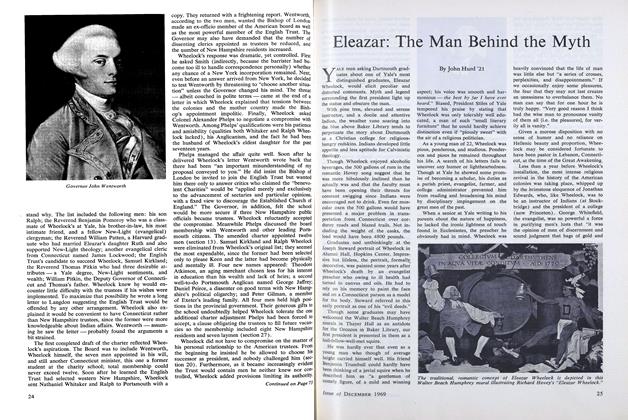

FeatureEleazar: The Man Behind the Myth

DECEMBER 1969 By John Hurd '21 -

Feature

FeatureEducation's Marshall Plan

JULY 1967 By ROBERT H. WINTERS, LL.D.