Publication some months ago of Webster's Third New International Dictionary aroused sharp criticismin some quarters because, it wasclaimed, the new unabridged edition included modern vulgarismsand failed to establish any standards of good usage. In all the hubbub the central issue became: Whatis the real function of a dictionary?Is it supposed to be an arbiter aswell as a compilation of all thewords in common usage?Dr. Philip B. Gove '22, editor-inchief of the new dictionary, was invited by the ALUMNI MAGAZINE tostate what he believes the functionof a dictionary to be; and he verykindly consented to write this article especially for us.

EDITOR-IN-CHIEF, MERRIAM-WEBSTER DICTIONARIES

THE function of a dictionary is to serve the person who consults it. Publishers know something about why a person buys a dictionary. Why and when he later consults it is another matter. A thousand people who open a dictionary could be motivated by a thousand different stimuli. Clearly, there must be some rules which a consulter is rather strictly required to follow.

The consulter of a dictionary should not open it to find out who won the Ivy League football championship two years ago or how to make 500 gallons of New England rum. He would not find out how many pheasants a licensed hunter can shoot in South Dakota during the open season or what towns in Kansas have local option. He would not discover how many sonnets Wordsworth wrote or how many grandfather clocks made by Joseph Gooding of Dighton, Mass., are still ticking. If he were to look expectantly for such information, he would at best merely be revealing his utter unfamiliarity with dictionaries; more seriously he could be disqualifying himself for a merit scholarship.

If, however, a consulter wants to know what possible use Eleazar Wheelock might have had for a Gradus ad Parnassum, he might conceivably find the answer in a dictionary. He might be able to find out the population of South Dakota - humans, not pheasants - and the area of Kansas. Even these questions, however, lie in a special area not strictly lexical. If a dictionary restricts itself by design to the generic vocabulary, a consulter who looks in it for nongeneric information is asking it to perform a service for which it was not built. I will restrict my consideration of the function of a dictionary to an unabridged monolingual dictionary of our generic English vocabulary.

An ideal dictionary would seem to me to be one in which a genuine consulter can find right off a satisfactory answer to a proper question. The matter of a proper question should concern spelling, pronunciation, etymology, meaning, function, or status, for these are the six kinds of information generally given explicitly or implicitly for each word. By far the most important of these is meaning, which for most words is the chief concern of a lexicographer.

A genuine consulter is one who wants or needs to know something about a word he has heard or read or who wants to know how to use a word in speaking or writing. Since readers in our civilization outnumber writers several thousand to one, the most important function of a dictionary is to enable a reader to find out what a word means so that a passage read can be understood, so that what its author intended can be figured out. A consulter of a dictionary who does not have a context into which to fit a meaning he looks up is not a genuine consulter. He may be motivated by a desire to criticize or to find out how a dictionary treats a word or by several other secondary or tertiary desiderations. He is not looking in a dictionary for a key to open a door to understanding. His findings, though sometimes made articulate, if not vociferous, are relatively trivial.

If a consulter is a writer, a dictionary is chiefly concerned with letting him know what meaning his readers are likely to put on a particular word in a particular context. A dictionary does not undertake to tell him what someone thinks his readers ought to understand. There is no point in telling anybody that the word arrival ought to be reserved for a "coming to shore by water" if no one understands or uses it that way. A dictionary is not concerned with telling a writer how he should write. That's his business, in which he must serve as his own arbiter.

The difficulties of using a dictionary are often attributed to the dictionary maker, as if he were responsible for all the complications in the language. The English language is infinitely complex and extremely difficult. No one person can ever master it. There is no formula for making it easy and simple and no panacea for those who stumble around in it in a daze. The reducing of this complexity to some kind of ordered presentation which can most of the time give a consulter the guidance he seeks is one of the lexicographer's chief accomplishments. When a dictionary fails a consulter, it is often either the consulter or the language which is responsible.

For whom is an unabridged dictionary made? Not for foreigners and not for children. The definitions in it are not written under an assumption that the consulter is totally unacquainted with the word being defined nor under any unwieldy or fantastic idea that the word he is looking up belongs on a scale at some vague point above which he cannot rise. Outside of contests or quizzes (or bets) words do not exist by themselves; they are surrounded by other words and live in a context of associated and related ideas, from which a consulter takes to the dictionary some little bit of understanding. The definition he finds helps him to fit a word into a frame, which is his objective in consulting a dictionary. If it fails to help him, because the subject is difficult or unfamiliar, he may give up, for lack of genuine and compelling interest, lack of time, or lack of ability or background. Not all words are for everybody. Definitions in an unabridged dictionary are written for adults of all kinds and degrees of interest and intelligence. Yet every user of the language is continually getting into semantic problems over his depth.

For the majority of situations in which a dictionary is consulted for meaning, words may be roughly divided into three groups: (1) Hard words which circumstances make immediately important: "The doctor prescribed synthesized cortisone." "Recidivism is a serious criminal problem in some urban communities." "Existentialism is a subjective philosophy." (2) Words frequently seen, usually understood loosely, but suddenly or recurrently unstable (for the individual): synthesize, urban, and subjective in the preceding sentence. (3) Common familiar words which unexpectedly need to be differentiated, such as break vs. tear,shrub vs. bush, or specifically clarified, such as fable, adventure, shake, door, remainder, evil. Most people get by without having to clarify these common words in the third group until an issue arises to require clarification. Without such an issue definitions of these common words are frequently jumped on because the words look easy to the uninitiated, although in practice they are usually more difficult than hard words to define.

Although a dictionary can be misused and misinterpreted, a lexicographer keeps his mind on words rather than on people and tries with all his diligence and percipience to tell the truth about them. The only area in which the truth may be found is actual usage. In fine, the function of a dictionary is to reflect the facts of usage as they exist.

Philip B. Gove '22

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCOMMON MARKET

May 1962 By WALDO CHAMBERLIN -

Feature

FeatureA Reporter in Washington

May 1962 By ERNEST L. BARCELLA '34 -

Feature

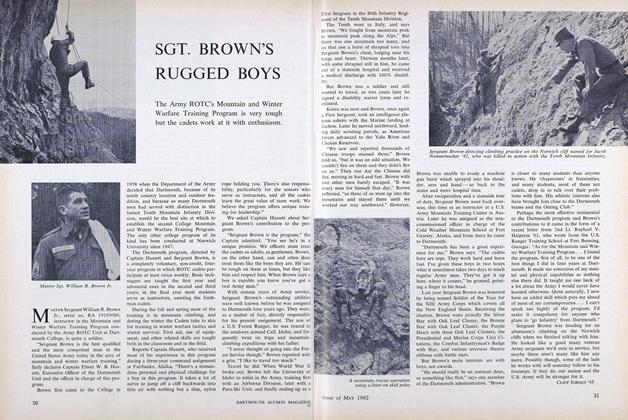

FeatureSGT. BROWN'S RUGGED BOYS

May 1962 By CLIFF JORDAN '45 -

Feature

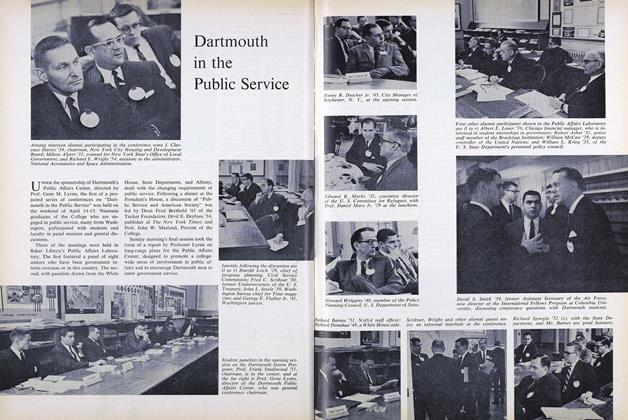

FeatureDartmouth in the Public Service

May 1962 -

Feature

FeatureMUSIC ADVISORY GROUP TO AID HOPKINS CENTER

May 1962 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1922

May 1962 By LEONARD E. MORRISSEY, CARTER H. HOYT

Features

-

Feature

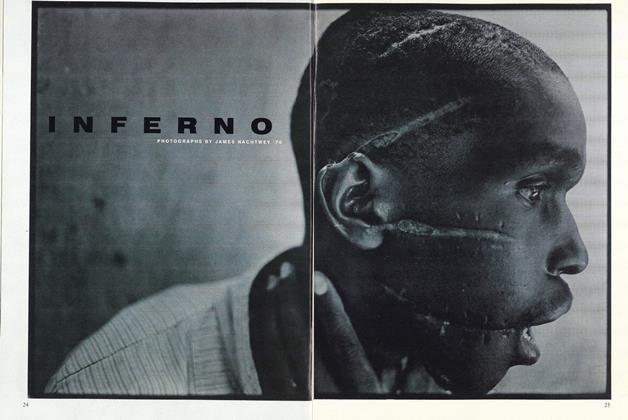

FeatureInferno

JUNE 2000 -

Cover Story

Cover Story"Be Prepared For The Unexpected"

Mar/Apr 2009 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO HOST AN UNFORGETTABLE CHEESE PARTY

Jan/Feb 2009 By CAI (BOLDT) PANDOLFINO '97 -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By HANSON W. BALDWIN -

Feature

FeatureONE HUNDRED MASTER DRAWINGS

October 1973 By ROBERT B. GRAHAM '40 -

Feature

FeatureFinal Assembly

October 1951 By THE HONORABLE JOHN GEORGE DIEFENBAKER