How I Overcame Lingering Thoughts About The Immorality Of Computers, Edited A Newsletter And Changed My Life In One Week ...

December 1987 Jack Aley '66How I Overcame Lingering Thoughts About The Immorality Of Computers, Edited A Newsletter And Changed My Life In One Week ... Jack Aley '66 December 1987

You NEVER ask anyone at a reunion or a football game why they came. Dumb question. But that's the first thing you want to know of others in a continuing education program, such as Dartmouth's Computer Alumni College. The program, in its fourth year, drew 64 participants from 19 states. The alumni and their family members who came gave reasons for attending as varied as their ages and occupations. Said one woman: "I wanted to be away from home, by myself, to completely immerse myself in computers. I wanted to grab hold of the 21st century."

Midway through the week-long course, a student tutor asked me what, to my aging mind, were the biggest changes at Dartmouth in the past 20 years. "Women and computers," I replied without hesitation. "But not necessarily in that order."

In the middle 19605, Dartmouth offered its students a monastic existence in which an English major like myself could (as I did) submit all papers written by hand and have at least one professor call the format "charming." John Kemeny, computing pioneer and now Dartmouth president emeritus, was a shadowy denizen of a basement across the way from Thayer Hall. He worked with a select group of students hardly anybody seemed to know. His computer had the heft of a truck and the memory of a pea.

I graduated blissfully ignorant of computers and remained that way for 20 years. I harbored the technophobe's view: computers were intrinsically evil and had no place in a humanistic society. Any device called a "word processor" that reputedly made writing "easy" could be nothing but innately immoral. God made writing hard for a reason.

So how was I convinced to attend Dartmouth's Alumni Computer College? Early in 1987 I had signed a contract to write a book about Maine. My publisher strongly urged that I put the work "on disks." I said I would, so long as disks would fit the 40-year-old Underwood typewriter I had inherited from my father. Writing, I felt, was enhanced by old typewriters.

About the same time, I became director of the fledgling land trust in my coastal hometown in Maine. One of the trust's members, a computer expert, loaned us an old computer for the office. He also delivered a word processing system with the catchy title Word Star and offered to teach me how to use it.

Suddenly, I felt like the object of a conspiracy. A daunting challenge had been tossed in my lap. And being a sucker for challenges, I had no choice but to give it a try. I secretly hoped, however, that I would fail my entry into the late 20th century and along the way have my prejudice against computers resoundingly confirmed.

Alas, I finished the book one month earlier than expected. The writing process on a "disk" was at least 30 percent faster than on my Underwood (no carriage returns) and the final product was better written than anything I'd produced in the past 15 years. Also, the land trust work was accumulating. My consultant started to explain computer capabilities that would make my work easier, such as databases and mailmerge. "Those things are really possible?" I asked.

While not exactly hooked when I signed up for the Alumni Computer College, I was getting intensely curious. I began the course with a much more open mind toward computers than I ever had believed possible.

I was immediately struck by how old the group was. I really didn't expect the 65-and-over crowd to care much about computers. "I'd rather die ignorant of the damn things," is what I expected of them. After all, that had been my attitude. But, on the contrary, at least 14 of the 70 enrollees came from the class of 1945 or before. They wanted to bridge communication gaps with family members ("Everybody in my family is a computer wizard; I feel left out of too many conversations") and enrich their retirement by learning new skills ("I want to write the history of my law firm on a word processor").

The younger members of the Computer College came for a variety of reasons, many, not surprisingly, related to their professions.

One woman, an intense yet engaging intellectual I came to call the "shark lady," wrote academic books about the brain cases or neurocrania of extinct cartilaginous fish. The process was for her—an impossible perfectionist—an agonizing succession of writer's blocks she hoped word processing would assuage. "I want to stop erasing," she said. "It's ridiculous to erase when you can delete and insert." Her husband, a Dartmouth alumnus, had come to study desktop publishing in order to produce a newsletter for dentists.

I stumbled across a woman from New York City, the mother of a Dartmouth student, as she dashed madly from one building to another. The sunlight seemed to make her wince. "God, I hate all the trees and all the green," she said. "One week is enough for me up here. But when I saw the computer charge on my daughter's tuition bill, I said to myself, Those guys are really serious about this. I think I'd better find out what I'm paying for.' "

And then there was the arresting motivation of an alumnus of my era, a public prosecutor from Tennessee. "I came because my secretary has become the overlord of the database in my office. I hired her on a temporary basis and now I can't get rid of her because she won't share information. I've got to learn about databases to protect myself."

Even the strongest motivation needs frequent nourishment. In the candy machine at the Kiewit Center, the omphalos of computering on campus, are disks. The Mac Disks, basic computer fodder at Dartmouth, sell for three dollars and are sandwiched between the Juicy Fruits and Ginger Snaps and Snickers. I found them one day while looking for a Snickers, a source for the energy to continue the course.

You needed a few extra Snickers to get through the week. Each day consisted of morning lectures followed by two hours of "hands on" time and afternoon lectures followed by three more hours of actual practice with the computers. In addition, there were three evening lectures. By Wednesday, we had been thoroughly inculcated in word processing, spreadsheets, databases and desktop publishing.

Especially frustrating for many was getting the hang of the "mouse," the kinesthetic device that drives our Macintosh computers. The mouse drove most of us nuts and not a few of us to swearing. One East Coast lawyer was given to street language that in any other civilized context would have been abusive. But in our computer labs, his epithets were cathartic. He got a lot of laughs.

Conducting this intensive introduction to computers were three instructors, one each from the geology, social science and math departments. They were all dedicated computer buffs. The interdisciplinary approach underlined the fact that computers touch every facet of Dartmouth's academic life. The implication—perhaps even the point of the course—was that computers could touch every facet of our lives. "If you live with a personal computer for six months," said one instructor, "your life will be changed forever."

Supplementing the lecturers was a cordon of long-suffering tutors, all Dartmouth students or recent graduates. After a lecture on word processing or databases, we students retired to one of five computer labs on campus to work on assignments designed to illustrate the lecture. It was the tutors' job to hold our hands and get us through the inevitable frustration of completing the assignments. Many thought that there too few tutors. It was common at first to get hung up on some purely mechanical problem of moving the mouse around the screen and have to wait for help, fuming, for 15 to 20 minutes.

On the other hand, the Computer College was well prepared for the various levels of expertise and special interests students brought to the course. For example, I enjoy foreign language and asked whether there were any language instruction programs to examine. The next day, a tutor brought me three disks which featured Germanlanguage drills, and she taught me how to use them.

My roommate, a lawyer from Kentucky, was a sophisticated computer user of many years and owned a computer business on the side. He admitted that it was in part nostalgia that brought him back to Dartmouth but also the desire to learn to program "C," something he tried patiently, though futilely, to explain to me. He disappeared frequently with his own computer tutor and had a Cheshire-cat smile on his face at week's end.

In spite of the emotional ups and downs of the days, the evening lectures were well attended. The most eagerly anticipated was John Kemeny's lecture on the night of the first day of class. Kemeny's talk about the past, present, and future of computing was provocative and wide-ranging and included an aside about word processing, a computer function he thinks is overrated, or at least overused.

"The best of all worlds is having a secretary who is an expert on word processing," Kemeny said. "Not so," my friend the prosecutor from Tennessee urgently whispered in my ear. "Not if she's also got the database and hordes it!"

The highlight of the week for me was being named editor of the computer college newsletter. My staff and I had less than 24 hours to get the paper out and to do it we had to utilize many new skills—word processing, graphics and desktop publishing. About 15 of us, ranging in age from 15 to 70, threw ourselves into the project heart and soul.

I assigned some dozen stories and sent the reporters to their word processors. Fifteen-year-old Jamie Loughlin of Long Valley, New Jersey, the youngest student (he came with his alumnus father), offered to be my graphics assistant. Jamie, despite his youth, became an important and aggressive member of the team. He designed the logo for the newsletter, which we all agreed to call "The Mouse Trap."

Friday afternoon came and the pressure mounted. We had five hours to get out our rag. A kindly professor from the English department miraculously appeared and offered to help me edit the copy being produced on 12 separate computers. We encountered huge obstacles in transferring the stories from separate word processors to our one desktop program. By midafternoon I was going completely out of my mind.

Two hours from deadline, one of the tutors stopped by to see if he could help. He was a virtuoso (also, possibly a plant—he passed out business cards). Stymied as we were, we were perfectly set up to absorb and appreciate the computer being used at nearly its full potential. Seventy-five copies of the "Mouse Trap" were delivered to the entire class ten minutes before the graduation dinner Friday night.

In an editorial for "The Mouse Trap" I made a modest proposal for the future of Dartmouth education: "Kick out the kids. Bring on the old folks like us. And grant us our degrees when we are 40 or 50 or 60—only when we have properly demonstrated a recurring lust to learn.

"Oh, I don't mean remove the youngsters entirely. I wouldn't mind a few of them around. Just accelerate the existing trend. There's nothing like a term or two in Paris or on an oil rig in the Gulf of Mexico to enlarge young people's databases and to make them more receptive students when they return to Hanover.

"And to take the place of the absent oil riggers on campus, enter the diverse student body of a Computer Alumni College '87. We truly belong here. We make great students. We already have extensive databases. We are intellectually hungry and perfectly motivated. We don't give a damn about grades.

"So I ask Dartmouth to keep hammering away at continuing education. To the degree that the College intensifies its commitment to programs like CAC, the educational climate at the place will improve here for young and old alike.

"For my part, I don't much care for the reunions and the football games. But I'll come back here at the drop of a hat for a bash at French or computers or Shakespeare. And I don't think I'm alone."

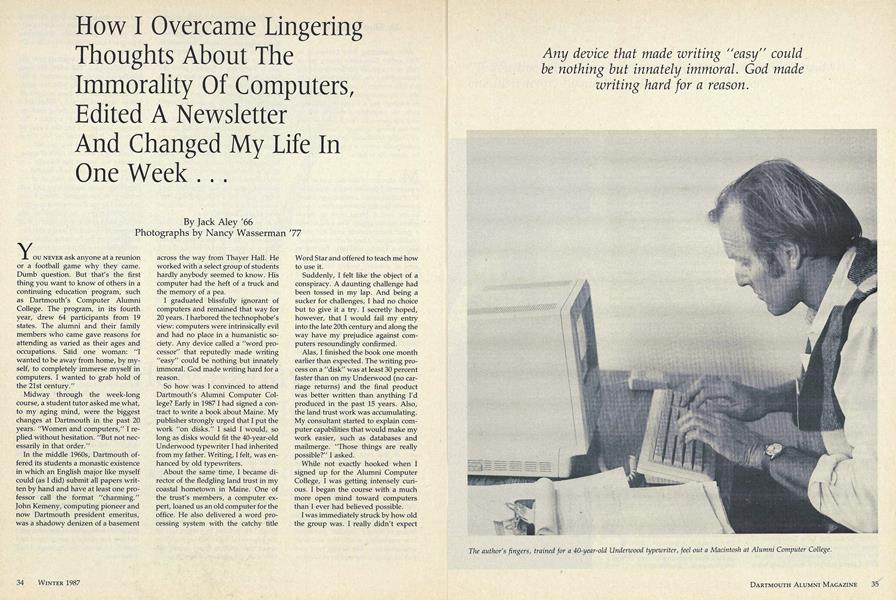

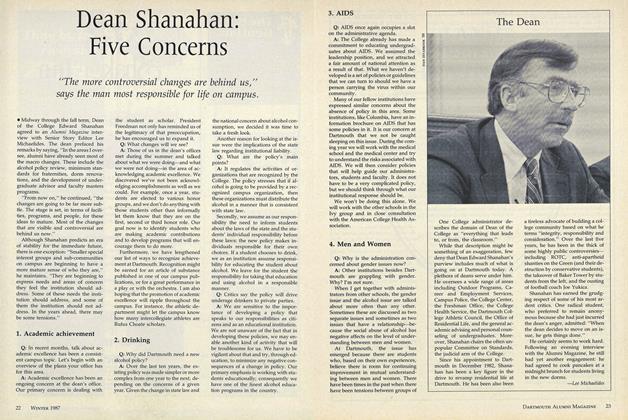

The author's fingers, trained for a 40-year-old Underwood typewriter, feel out a Macintosh at Alumni Computer College,

The class gets a software demonstrationfrom Daniel H. Krymkowski, assistantprofessor of sociology and one of thecourse's three instructors. "They were allcomputer buffs," says the author.

The mouse . . . Computer College student Howard Wilson '41 seizes thekinesthetic device that controls the Macintosh computer.

is an animal . . . During five hours of practice every day, the mouse"drove most of us nuts," says author Jack Aley.

that rewards . . . A professor once called a hand-written paper "charming."Computers now touch every facet of academic life.

the skilled.Participants ranged- in age from 15 to 70, and planned toapply their computer literacy in equally diverse ways.

Any device that made writing "easy" couldbe nothing but innately immoral. God madewriting hard for a reason.

"If you live with a personal computer for six months," saidone instructor, "your life will be changed forever."

Jack Aley's first book, "Wild Brothers:Maine Animal Tales," will be published byLance Tapley, Publisher, early this month.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Loss of Jacob

Winter 1987 By Peter Dorsen '66 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIf I Could Do It Over

Winter 1987 By Timothy J. Burger '88 -

Feature

FeatureHow to Buy a Mattress in India

Winter 1987 By Elise Miller '85 -

Feature

Feature5. Residential Life

Winter 1987 -

Feature

Feature4. Men and Women

Winter 1987 -

Feature

Feature2. Drinking

Winter 1987

Jack Aley '66

Features

-

Feature

FeatureWHY a Hopkins Center at Dartmouth?

October 1961 -

Feature

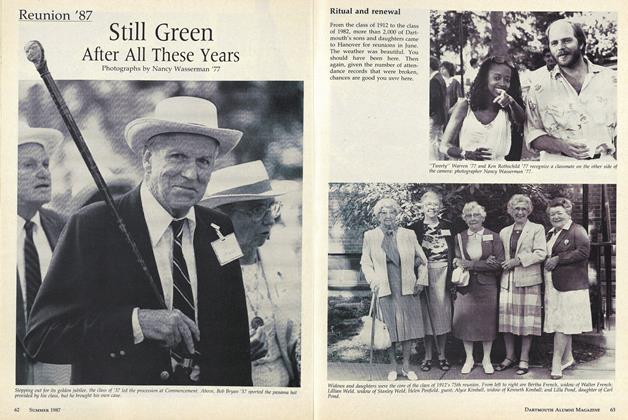

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987 -

Feature

FeatureHAIR

November 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureAlumni and Tuck Faculty Join In Study of Stock Ownership

January 1955 By JAMES P. LOGAN -

Cover Story

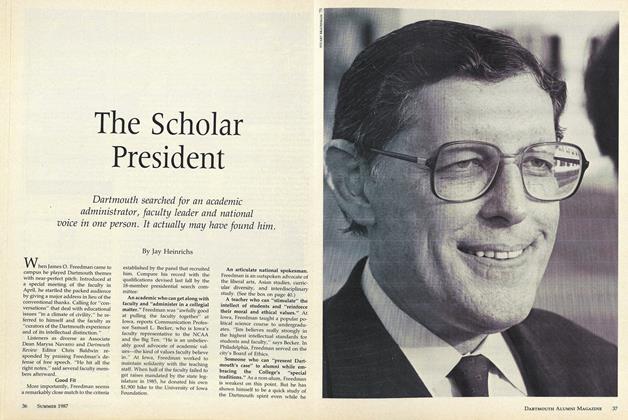

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe Seniors' Valedictory

July 1956 By WILLIAM FREDERICK BEHRENS '56