A Deafie's Super chat

Ken Glickman, born profoundly deaf, graduated magna cum laude from Dartmouth in 1977. A computer programmer with IBM, he has written a collection of terms that poke fun at both "deafies" and "hearies" while offering insight into the not-so-silent world of the deaf. Here are a few examples from his book, "Deafinitions for Signlets" (DiKen Prod- ucts).

ACCELEPRATE v. To chatter at an increasingly incoherent speed.

CABOOSED adj. Being the last to know about the latest rumor. (Used especially for DEAFIES in a hearing environment.)

DEAF-IMPAIRED v. Anyone who is not hearing-impaired; a HEARIE.

DEAFIE n. A deaf person who acts and looks like one.

HEARIE n. One who hears most, if not all, of the ordinary sounds; DEAF-IMPAIRED.

HEARING AND DUMB adj. A term that best describes HEARIES who keep referring to DEAFIES as "deaf and dumb."

HUMORIBUND v. To try to convince a DEAFIE that the joke he just missed wasn't funny anyway.

INTERPRIVY n. A private conversation between an interpreter and a lone deaf client especially during a boring lecture.

JETSTARTING v. Trying to start a car when it's already running.

NARCOLEPSIGN v. To communicate in sign language while asleep.

STOMPOPHOBIA n. The fear that some DEAFIES have of somebody banging on the floor (with feet) or on the table (with hands) right behind them to get their attention.

SUPERCHAT v. To carry on a leisurely conversation through the huge storefront window at a supermarket.

VACSUCKER n. A DEAFIE who continues vacuuming after the plug is inadvertently pulled out its socket.

VISUCLAP v. To applaud by waving handkerchiefs or napkins, especially at DEAFIE reception dinners or banquets.

WAVILY v. To say farewell with the "I love you" hand sign (three fingers spelling I, L, and Y simultaneously).

Oedipus at Home

Poet David Graham '75 writes verse that often crackles with intense autobiography. This excerpt from the poem "American Gothic" appears in his first collection, titled "Magic Shows" (Cleveland State University Poetry Center).

Mom kept her old address book a secret, hidden under her voluminous underwear in a dark oak dresser. Of course I peeked, as I was meant to, but I do not think I was supposed to fall in love with the brown-gray photos of that college girl, strange as late night movies. I was young but her truth was younger. And Dad kept his secrets some place I never found, though it's possible I didn't look hard, as I turned away my eyes each time he rose dripping from the bathtub.

Myth as National Catalyst

In this passage from "The Juarez Myth in Mexico," Charles A. Weeks '60, a teacher at St. Andrew's Episcopal School in Jackson, Mississippi, describes the cultural legacy left by Benito Juarez, president of Mexico between 1857 and 1872.

When Mexicans refer to Juarez as a champion of nationalism or democracy they treat the historical personality in such a way as to create a symbol, something that is itself and more. Mexicans have attributed meanings to Juarez that express what they want to believe about him and the time he lived. The result is a hero or a villain—depending upon the particular set of values and beliefs of the speaker or writer. The myth creates an intelligible reality by breaking down distances between present and past and present and future so that in effect all is present; it thus satisfies a basic human need to make the present and the future more intelligible by references to the past. Thus in a sense nations are the creatures of their my thmakers; it is their image of the past that produces an image of present and future.

Parenting the Grandparents

In "Ties that Bind: The Interdependence of Generations" (Seven Locks Press), Eric R. Kingson, Barbara A. Hirshorn and John M. Cornman '55 describe the increasing moral burden that younger generations encounter in caring for the elderly. Cornman is executive director of the Gerontological Society of America.

While there is some historical precedent in both Far Eastern and some Western history for filial responsibility toward the old as a tradition, there are two reasons why filial responsibility is fairly new as a major motivation for intergenerational care-giving. First, until the advent of an aging society, relatively few families were faced with the question of providing care for older people. And second, until the end of the nineteenth century, older family members owned the means of production (farms, farm equipment, etc.) until death, which made intergenerational relations more a question of economic survival than of filial responsibility. However, industrialization at the turn of the century took the means of economic survival out of the hands of parents. The decision to take care of elderly family members thus changed from one of necessity to one of choice, and the value of filial

Illustration of "wavily" from "Deafinitions for Signlets"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

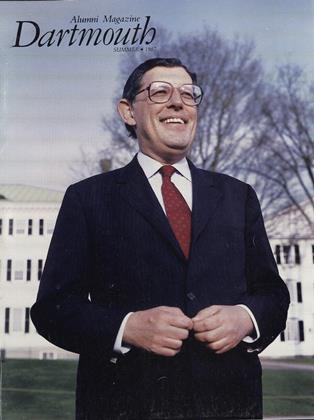

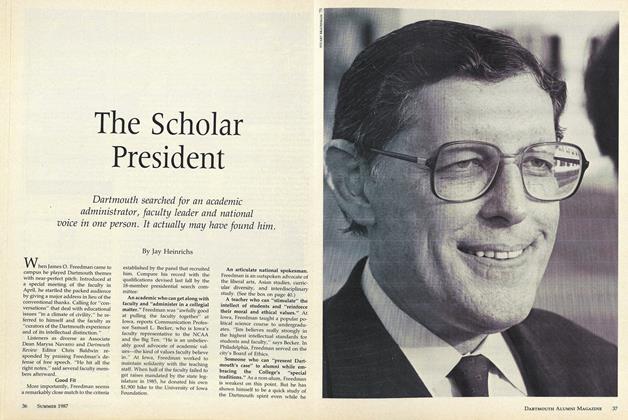

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

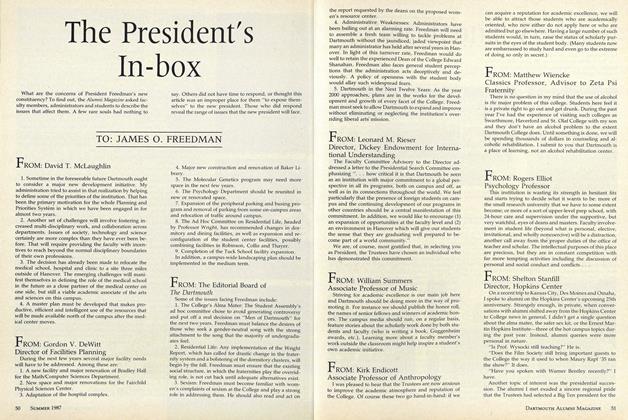

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

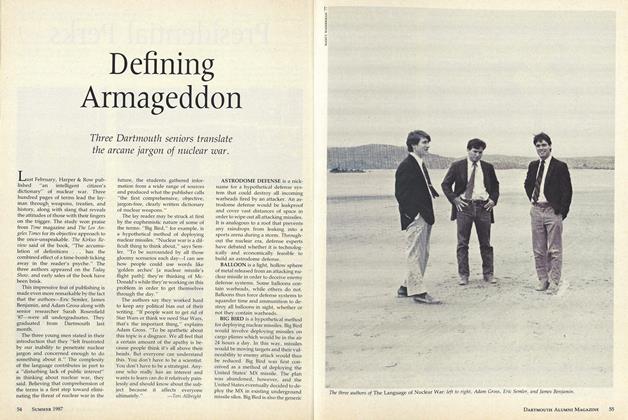

FeatureDefining Armageddon

June 1987 -

Feature

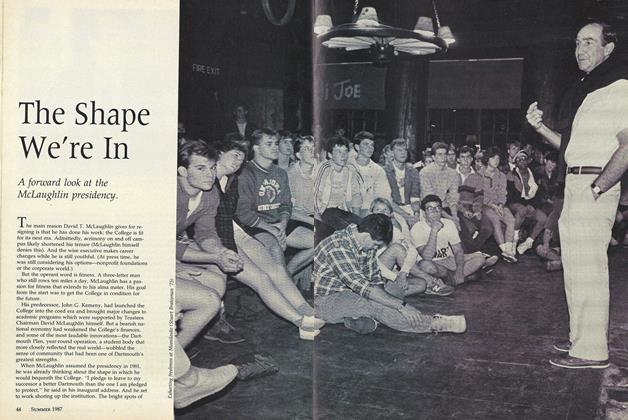

FeatureThe Shape We're In

June 1987 -

Feature

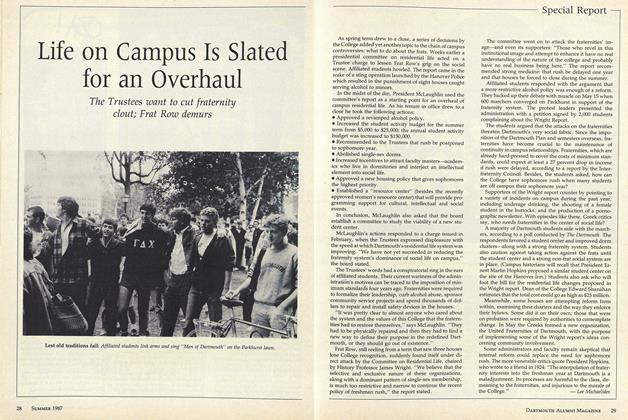

FeatureLife on Campus Is Slated for an Overhaul

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

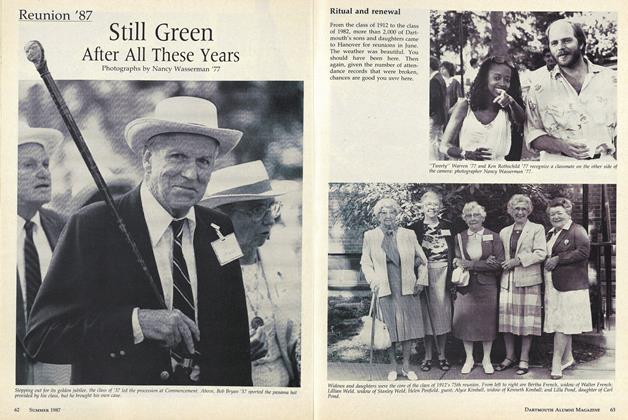

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987

Article

-

Article

ArticlePRESIDENT NICHOLS' ADDRESS AT THE OPENING OF COLLEGE

November, 1910 -

Article

ArticleIn Line of Duty

February 1945 -

Article

ArticleAt The Dartmouth, Knowing Smiles

JAN./FEB. 1978 -

Article

ArticleFurther Mention

November 1973 By J.H. -

Article

ArticleCONGRATULATIONS:

February 1934 By S. C. H -

Article

ArticleWith the Outing Clubs

January 1937 By William B. Rotch ’37