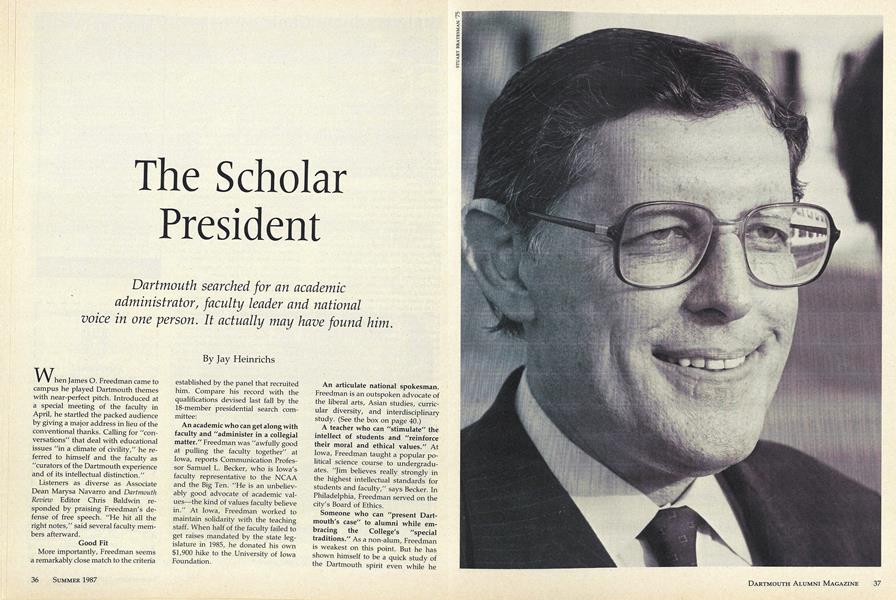

Dartmouth searched administrator, faculty voice in one person. It actually

When James O. Freedman came to campus he played Dartmouth themes with near-perfect pitch. Introduced at a special meeting of the faculty in April, he startled the packed audience by giving a major address in lieu of the conventional thanks. Calling for "conversations" that deal with educational issues "in a climate of civility," he referred to himself and the faculty as "curators of the Dartmouth experience and of its intellectual distinction."

Listeners as diverse as Associate Dean Marysa Navarro and Dartmouth Review Editor Chris Baldwin responded by praising Freedman's defense of free speech. "He hit all the right notes," said several faculty members afterward.

Good Fit

More importantly, Freedman seems a remarkably close match to the criteria established by the panel that recruited him. Compare his record with the qualifications devised last fall by the 18-member presidential search committee:

An academic who can get along with faculty and "administer in a collegial matter." Freedman was "awfully good at pulling the faculty together" at lowa, reports Communication Professor Samuel L. Becker, who is lowa's faculty representative to the NCAA and the Big Ten. "He is an unbelievably good advocate of academic values the kind of values faculty believe in." At lowa, Freedman worked to maintain solidarity with the teaching staff. When half of the faculty failed to get raises mandated by the state legislature in 1985, he donated his own $1,900 hike to the University of lowa Foundation.

An articulate national spokesman. Freedman is an outspoken advocate of the liberal arts, Asian studies, curricular diversity, and interdisciplinary study. (See the box on page 40.)

A teacher who can "stimulate" the intellect of students and "reinforce their moral and ethical values." At lowa, Freedman taught a popular political science course to undergraduates. Jim believes really strongly in the highest intellectual standards for students and faculty," says Becker. In Philadelphia, Freedman served on the city's Board of Ethics.

Someone who can "present Dartmouth's case" to alumni while embracing the College's "special traditions." As a non-alum, Freedman is weakest on this point. But he has shown himself to be a quick study of the Dartmouth spirit even while he speaks to the need for change. "This college has demonstrated a capacity to inspire its graduates with a love of the institution which is virtually unequalled in American higher education," he told the Dartmouth faculty in April. "It will be essential in the years ahead that we preserve the fundamental nature of the Dartmouth experience at the same time that we continually seek to refine and strengthen it."

Freedman also has a couple of skills riot mentioned by the search committee. These traits may be of some use at Dartmouth:

Administrative ability. He had the good fortune at lowa to take over a historically lean and scandal-free administration. Nonetheless, he deserves at least partial credit for an administration that still runs smoothly. In short, says William R. Grigsby, associate professor of periodontics at lowa and a '56 graduate of Dartmouth: "He inherited some good people and got them to do his bidding."

Fundraising savvy. Although lowa is not known for the kind of private support that Dartmouth gets, Freedman shows potential in the money department. Several years ago he travelled down the Mississippi to Muscatine, lowa, where he spoke to a service club—not on the Hawkeye football team or on farm policy but on Asian-American relations. One member of the audience later had his family donate $2 million toward a Center for Asian and Pacific Studies at lowa.

The Search

Candidate number 118, as Freedman was originally labelled by the search committee, is the end product of a remarkably rancor-free process. It contrasts favorably with the search that was conducted seven years ago after President John Kemeny resigned. At that time the trustees formed two committees, a sort of varsity and JV. The first consisted solely of six trustees; the second, which represented a variety of College constituencies, served under the trustees committee in a purely advisory capacity. Several faculty members later criticized that search for lack of sufficient input from academics.

This time just one committee conducted the search. The group consisted of seven trustees, four members from the faculty of Arts and Sciences, three professional school faculty members, three alumni representatives, and a student. Each member had an equal vote in the nomination—preceding final action by with the Board of Trustees.

The group solicited advice from 66,000 alumni, parents and friends of the College. Alumni sent back 625 replies, according to Norman E. McCulloch Jr. '50, chairman of the Board of Trustees and head of the search committee. He estimates that "90 percent" of these replies stressed academic credentials as the leading criterion.

The committee cast its net equally wide for candidates. It enlisted the services of a Chicago search firm, Heidrick and Struggles. The agency has coordinated 60 presidential searches, including those at Brown, Cornell, Colgate, Delaware, Kentucky, Miami, Duke, Indiana, Northwestern, Purdue, and Texas A & M. At a cost of something over $40,000 (an exact figure could not be obtained), the firm helped identify and contact candidates who were not actively looking—such as James Freedman. In fact, Heidrick and Struggles Executive Recruiter William J. Bo wen was the first to reach the lowa president, who at the time was also a candidate for the presidency of Indiana University, and had earlier been considered for Yale's top spot.

"If you are a sitting president it is difficult to answer an advertisement in the paper or to talk directly with another college," says Freedman. He adds that Bowen and his associates "were very helpful in creating circumstances that protected my privacy dur- ing the course of the search."

The search committee, in teams of three, interviewed 23 of the 615 original candidates around the country. Freedman was interviewed in early March, in Chicago. Nine semifinalists survived the next cut; five of these were heading colleges or universities. Five weeks later, in early April, the search committee voted unanimously on its first and only ballot to nominate Freedman. The Board of Trustees then met in special session in Hartford and gave the man from lowa another unanimous vote.

Why Leave?

Just a week before Freedman announced he was leaving for New Hampshire, he assured an interviewer: "My roots are in lowa." Nonetheless, he had cause to leave the state. "The basic reason for my departure [from lowa] is the attractiveness of Dartmouth College—the quality of faculty, the quality of the student body, the rich traditions of intellectual distinction, the strong loyalty of the alumni," says Freedman. "And, indeed, New Hampshire is one of the big attractions. When I graduated from law school in 1962 I took the New Hampshire bar and I expected to practice law in New Hampshire for the rest of my days. Life hasn't worked out that way."

On the other hand, Freedman had expressed frustration with the amount of time he had to spend at lowa defending liberal arts before a state legislature that occasionally seemed to think them a luxury. A dismal farm economy did not help matters. Neither did lowa's governor, Terry Branstad, who argued to the legislature that liberal arts were being stressed to the disadvantage of economic development. State support for instructional and academic programs dropped from 75 percent to 66 percent of the university's budget during Freedman's tenure.

"You can't expect a person of the caliber and qualifications of President Freedman to stay with an institution like the University of lowa when we're not even met halfway by the legislature and the governor's office," complained Joe Hansen, president of the Student Senate, to a local reporter.

William Grigsby thinks Freedman's motives fall somewhere between the attractions of Dartmouth and the penury of Iowa: "Dartmouth is a place where he can devote more of his energies to intellectual pursuits."

lowa Controversy

To Freedman's credit, perhaps the most universally unpopular thing he did as president of lowa was to leave it after implying he planned to stay. Monica Siegel, a daily editor of the student newspaper The Daily Iowan, called the act "somewhat disloyal," and other students said they felt betrayed.

The university and its president also experienced their share of protests over the administration's policies. Last year, students decried a stiff tuition increase that Freedman had supported to raise dismally low faculty salaries. Two years ago, students occupied the president's office for about 26 hours, demanding divestment of stock in companies that do business in South Africa; 136 students were arrested. Freedman came out against divestment but later went along with a committee of students and school officials who recommended a set of principles that resulted in the university's selling off all of the stocks. An administrative office was occupied again this year by students protesting CIA recruitment on campus. And his advocacy of a new laser laboratory for lowa has raised questions among pacifists about its possible use in research for the Strategic Defense Initiative or "Star Wars."

The biggest single flap of his tenure occurred last summer, when Freedman testified before Congress in favor of William Rehnquist's nomination as chief justice of the Supreme Court. Freedman says he met the judge while both were teaching a 3-week law seminar during the summer of 1979 in Salzburg, Austria and that he has remained a friend of Rehnquist ever since.

"William H. Rehnquist is a person of rare qualities... [which] the nation should cherish in the chief justice of a court with the ultimate responsibility for administering those wise restraints that make us free," Freedman told the congressmen. Critics at lowa noted that other congressional testimony alleged that Rehnquist had worked against black voter registration in the 1960s and had compiled an unimpressive record on civil rights as a Justice Department official under Nixon. Freedman's testimony in the face of these allegations "upset a lot of people," reports Samuel Becker.

"I testified for Bill Rehnquist because he is a friend," Freedman replied in an interview. "He asked me to testify. I truly felt that I could not live with myself if I had chosen not to testify for a friend because I feared the political repercussions."

The repercussions were slight by Dartmouth standards. But an editorial in the student newspaper The Daily Iowan maintains that the incident betrays the president's failure to speak to liberal concerns. While Freedman deserves credit for building lowa's academic strength, the editorial states, he "failed to establish the UI as a leader of social conscience."

Dartmouth Problems

Freedman might not be treated quite so gently at Dartmouth. lowa's senior administrators have shown themselves to be remarkably adept at protecting their president. For example, students protesting defense research at the university found themselves confronting the vice president for educational development and research. When students occupied the vice president's office over CIA recruitment on campus, the top staff advised Freedman to leave—which he did, after reciting the university's policy on recruitment.

The current administrators at Dartmouth, on the other hand, are not accustomed to taking the heat for their president. "This place is smaller and more intimate than lowa," says a Dartmouth official who asked not to be named. "It is a lot harder for the president to dodge the flack here."

lowa also contrasts with Dartmouth in faculty outspokenness. "Faculties have different personalities at different institutions," notes Freedman. "I suspect that the faculty is a little more feisty at Dartmouth." But he adds that he is committed to "collegial governing" and that such a system works well.

Criticism of Ereedman's politics will not be restricted to the left at Dartmouth. Conservatives are equally likely to find fault in his advocacy of a large and diverse curriculum. Past articles in the Dartmouth Review have repeatedly referred to programs such as black and women's studies as "junk food courses." Freedman does not like the term. "If one were to say that a course in black studies that teaches the work of Langston Hughes and Toni Morrison, Richard Wright and Ralph Ellison is a junk food course, I couldn't think of a more inappropriate, description," he retorts. "If one were to say that a course in women's studies that teaches Emily Dickinson, Jane Austen, and George Elliott is a jurik food course, I could not disagree more."

On the other hand, conservatives have already praised Freedman for his defense of free speech at Dartmouth. The past administration has come under attack for covering up the Hovey Grill Murals and Christian stainedglass windows in Rollins Chapel, failing to sponsor enough conservative speakers on campus, and refusing to cooperate with the Dartmouth Review. When Freedman was asked at a press conference whether the Review should be allowed on campus, he replied, "I think there's a difference between very bad taste and things that are bannable under the First Amendment."

Intimate Outsider

Observers disagree over whether Freedman's lack of previous Dartmouth connection is an added problem. The last president without previous ties to the College .was Bennett Tyler, a minister who came in 1822 and left six years later to head a church in Maine.

Clearly, Freedman has a lot to learn; he claims he does not even know the alma mater. But an editorial in the local newspaper, the Valley News, maintains that ignorance has its blissful side: "He will walk onto the Dartmouth campus with a minimum of green-colored baggage."

Colleagues from the past point to Freedman's adaptability. "When he came to lowa and discovered how important athletics is, this came as a great shock to him," recalls Samuel Becker. But now he really seems to enjoy it. This was a totally alien environment for him, and he really adapted and gained the respect of quite varied people—farmers, the governor, the legislature." Freedman now even claims to subscribe to Sports Illustrated.

Besides, some New Hampshire citizens say he is not an outsider here in the first place. He was born and grew up in Manchester, where his father was chairman of the high school English department. He retains traces of a New England accent, pronouncing "half" as "hoff." An editorial in the Manchester Union Leader asserts that, despite Freedman's unrivalled education and his stints as dean at Penn and president of lowa, "he really didn't go that far. About 85 miles, as we measure it."

What He'll Do

How far he will go at Dartmouth remains to be seen, of course, and he is understandably reluctant to discuss specifics. "The only mandate I have from the Dartmouth trustees is to maintain the intellectual quality of the College and do everything I know how to work with the faculty, students, and alumni," he says. "People are often very impatient for a new president to stake out his position on any number of issues. But to stake out positions wisely requires listening. And collegial governance means listening to faculty and students and alumni before indicating positions on things about which I'm not truly informed yet."

Some immediate tasks have already been set for him, however. A number of top administrative posts remain empty—including provost, five deanships and affirmative action director. In addition, Freedman recognizes the need to travel for speeches to groups of alumni, especially in his first year.

He also says he will continue some practices he started at lowa. He hopes to teach an undergraduate course sometime in the future. In addition, he plans to ask academic departments to invite him for brown bag lunches at which he will listen to faculty discuss their work. "I have been interested in the cross fertilization of disciplines," he remarks. "When I met with lowa's marketing faculty, for example, I learned that fewer than half had a Ph.D. in marketing. Most of the Ph.D.'s were in psychology, in anthropology, in law, in disciplines other than marketing."

Another lowa practice he will bring to Dartmouth is a twice-a-semester faculty seminar for senior administrators. At lowa, Freedman would invite two lecturers—mostly junior faculty for an afternoon to speak on their work to a dozen vice presidents and associate vice presidents. The officials heard some 35 lectures in five years. "These seminars have given faculty an opportunity to explain their work and the importance of it to members of the administration," explains Freedman. "We need to be reminded that the fruits of intellectual inquiry are what the institution is all about."

The veteran university president has few illusions about the direct changes a single person can effect on a campus. This attitude may, in fact, give the clearest indication of the style of his next presidency. "The fundamental attraction of the job," states Freedman, "is the opportunity to participate in setting an agenda for discussion on the campus—an agenda which engages an open conversation with the faculty, the student body and the alumni about whether the goals of higher education are the goals of this particular college."

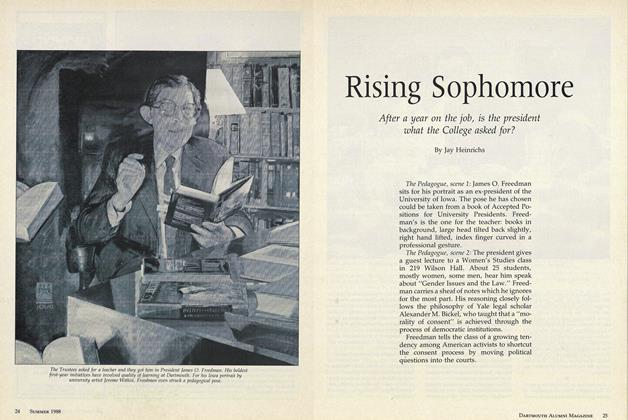

Just in from Iowa: McLaughlin escorts Bathsheba, Deborah and James Freedman. Bathsheba will teach psychology here.

Obviously pleased with his work: "This is the best job I've ever done," said Trustees Chairman McCulloch, showing off the search committee's find.

A faculty for faculties: the new president chats with English Professor William Cook and former President John Kemeny at a reception. As lowa's president, Freedman considered himself an academic among colleagues.

Comparing notes: the newcomer jots a tip from Kemeny. Freedman is the first Dartmouth president without previous ties to the College since Bennett Tyler, who came in 1822.

Best of luck: McLaughlin gives an encouraging sign at Freedman's introduction "It is harder to dodge the flack" at Dartmouth than at lowa, says one administrator.

Vita James Oliver Freedman Age: 51. Wife, Bathsheba, has a B.A. from Brandeis, an M.A. from Columbia and a Ph.D. in human growth and development from Bryn Mawr. She has been appointed a senior lecturer in psychology at Dartmouth. Two children: Deborah, 22, who graduated from the University of Michigan in 1986; Jared, 17, entering Harvard this fall. B.A., cum laude, Harvard, 1957. Worked summers as a reporter with the Manchester Union Leader and the New Hampshire Sunday News. Yale Law School, cum laude, 1962. Law clerk for Thurgood Marshall before Marshall became the Supreme Court's first black justice. 1964-1982: University of Pennsylvania. Taught law and political science. 1973-1976: Ombudsman, University of Pennsylvania. Mediated grievances among university members. 1979-1982: Dean, University of Pennsylvania. 1981: Chair, Pennsylvania Legislative Reapportionment Commission. Law School. 1980-1982: Member, Board of Ethics, City of Philadelphia. 1982-1987: President, University of Iowa. Also Distinguished Professor of Law and Political Science. 1987- : President, Dartmouth College. Says he plans to serve for at least eight to ten years. Has taught law at Michigan, North Carolina, Cambridge, Georgetown, and in Salzburg, Austria. Author of Crisis and Legitimacy: The Administrative Process and American Government (Cambridge, 1978). Has honorary degrees from Pennsylvania, Cornell College, and St. Ambrose College.

This Guy Reads One of the best ways to get to know a person is to ask his bookseller. This only; works, of course, if the person buys books. .WithJames O. Freedman, this is no problem. "You want to know if this guy reads? Let me tell you: this guy reads," assures Jim Harris, owner of the Prairie Lights Bookstore. "I'll put it this way," he adds: "When he leaves I'll have to refinance my debt. And I'm only partly kidding when I say that." His preferences? History comes first. Then current literature. He reads books on education, of course. When we visited Iowa in early May, his most recent purchase in Harris's store was the Oxford Book of Etymology. He col- lects the Oxford series. "He's the ideal customer," says Harris. "First of all, he buys hardbacks. In cash. He comes often, at least twice a week when he's in the country; that reinforces my buying strategy. He's also very pleasant. Which leaves one question: when does a university president have time to read? "At night a little, on airplanes a lot," Freedman replies.

What He Did At lowa The longest set of lowa "achievements" in a report that James Freedman gives reporters lists "outstanding appointments for key positions." He is much more reluctant to take credit for the other successes of his administration. He began his lowa presidency with a speech calling for a "covenant with quality"; in the following five years the state university toted up a record of achievements that belies Iowa's economic plight during that period. Below is a partial list of accomplishments directly attributable to Freedman or carried out during his tenure. • Established the university's largestever fundraising campaign, an effort to raise $100 million in private contribution to be devoted entirely to an endowment for professorships and fellowships. So far, $55 million has been raised, and the goal has been increased to $15O million. • Reallocated funds to what he called "centers of excellence"—thereby steering scarce resources away from weaker programs. • Inaugurated the Center for the Book—a program that combines book- binding, book conservation, papermaking, the history of the book, and type design. • Established an undergraduate scholar assistant program, in which outstanding students receive credit and a stipend to conduct research with professors. • Revitalized the honors program. lowa had not had a Rhodes Scholar in 15 years; two students received Rhodes Scholarships within three years of Freedman's taking office. • Established a Center for Asian and Pacific Studies and a Center for International and Comparative Studies. • Established with a Ford Foundation Grant the lowa Critical Languages program, which prepares lowa under- graduates to be high school teachers of Chinese, Japanese and Russian, • Worked out 42 exchange agreements with universities abroad, • Travelled to Indonesia, Austria, The People's Republic of China, Japan, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Israel, Iceland, Italy, and Germany to establish foreign exchange programs, confer on internanational education, or participate in lowa's outreach programs, • Oversaw construction of several major facilities, including a communication studies building, a new law school building a Ronald McDonald House for sick children and their families, and a human biology research facility. • Made more than 300 speeches, formal reports, and presentations nationally and internationally. Wrote two scholarly articles, a book review, and scores of newspaper pieces and journal essays. Taught an undergraduate course for three semesters, titled "Individuals and Institutions."

From the Podium "I certainly want to use the Dartmouth presidency as a podium for speaking nationally," Freedman told an interviewer recently. He leaves no doubt about his personal beliefs. Below are a few quotations from past speeches and articles, and from remarks he made to the Alumni Magazine in May. Ww have opened our curriculum [at lowa] because we recognize that, in a pluralistic and evolving universe of knowledge, a university would be shortsighted to teach only those principles by which knowledge is organized at any one time. We recognize that the task of intellectuals and educators is to develop the organizing powers of the next generation of scholars, rather than to present them with a preselected packet of information." Iowa faculty convocation speech, 1986 Civility toward one: another, tolerance of maddeningly different points of view, is essential to the maintenance of a community of scholars and to the passionate exchange of ideas." Speech to the Dartmouth faculty, April 1957 Presidents as well as professors must understand that the measure of the scholar's thought is the source of a university's vitality and the standard by which it must judge itself. Nothing else... has value,except as a means to that end." —Essay in the Chronicle of Higher Education, February 1986 Fifty years after our students 1 graduate they will likely live in a world dominated more by the nations of Asia than the nations of western Europe. It is therefore essential that we introduce into our curriculum more opportunities lor students to learn about these nations." —Alumni Magazine interview

Editor Jay Heinrichs visited lowa in May.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

FeatureDefining Armageddon

June 1987 -

Feature

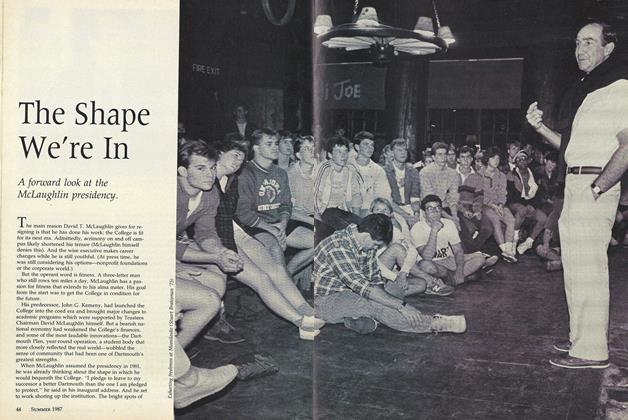

FeatureThe Shape We're In

June 1987 -

Feature

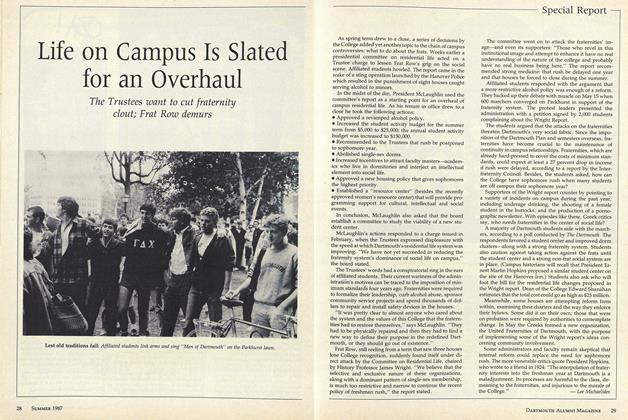

FeatureLife on Campus Is Slated for an Overhaul

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

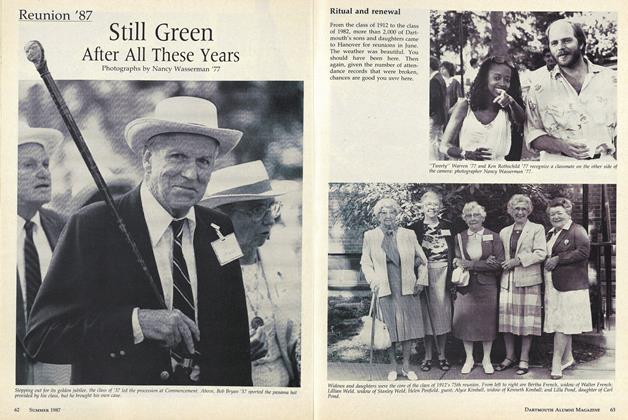

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987 -

Feature

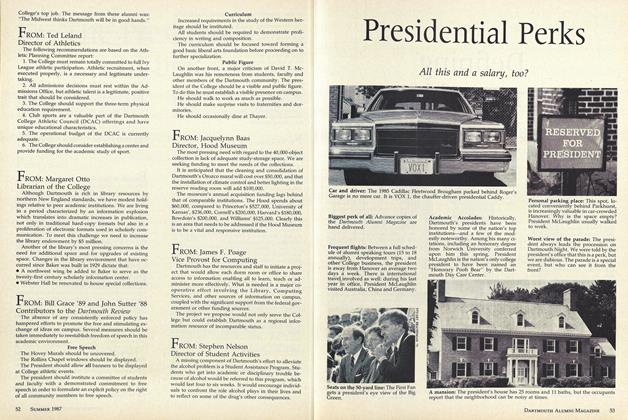

FeaturePresidential Perks

June 1987

Jay Heinrichs

-

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

MAY • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureRising Sophomore

June • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE THIRD WORLD'S LOW-KEY CRUSADER

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleENGINEERING THE FUTURE

FEBRUARY 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleStatement of Ownership, Management and Circulation (required by 39 U.S.C. 3685).

December 1995 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Cover Story

Cover StorySecond Nature

OCTOBER 1996 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Feature

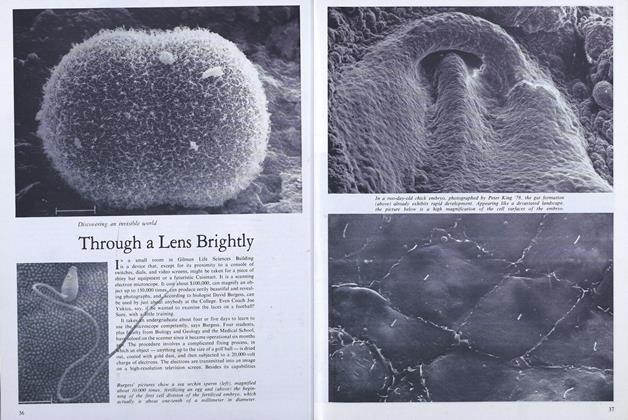

FeatureThrough a Lens Brightly

MAY 1978 -

Feature

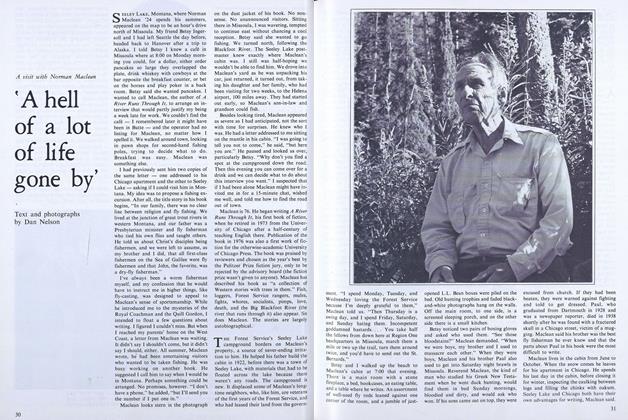

Feature'A hell of a lot of life gone by'

November 1978 By Dan Nelson -

Feature

FeatureStar Birth, Star Death, and Black Holes

February 1975 By DELO E. MOOK -

Feature

FeatureThe Vanishing Ability To Write

OCTOBER 1962 By George O’Connell -

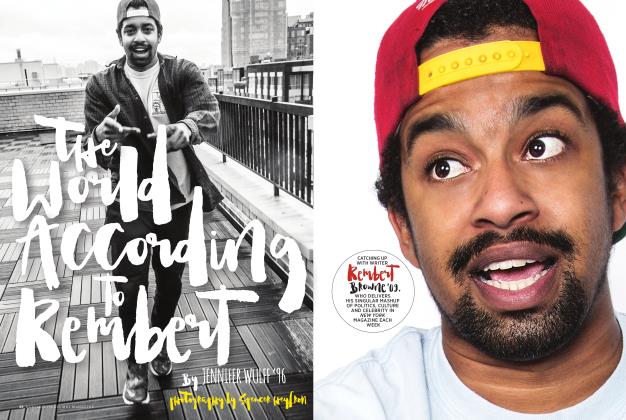

COVER STORY

COVER STORYThe World According To Rembert

JULY | AUGUST 2016 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureHonorary Degree Ceremony

October 1951 By SIR WILLIAM HALEY