One of the College's touchiest issues came to a head during Dartmouth Night, just as the crowd rose to sing the alma mater in front of Dartmouth Hall. A group of students calling themselves "wombyn to overthrow dartmyth" ("wombyn" because "women" is derivative of "men") dressed up in disguises, approached the podium where President McLaughlin had just spoken, and scattered mock bloodied tampons on the grass.

Few people on campus supported the protest—many of even the most ardent feminists were disgusted. While the "wombyn's" action was the most confrontational of the year, however, it was by no means an isolated incident. Sexism has become a major concern at Dartmouth one that underlies some of the most well-publicized issues, such as the alma mater and the role of fraternities on campus. The subject has become a touchy one; it is tricky even to hold a decent discussion without offending somebody. In fact, the touchiness surrounding the issue makes this the most difficult column we have ever written.

On the other hand, one person's touchiness is another's sensitivity. The community seems to realize at last that there is a problem that must be addressed. And attitudes have begun to change, if slowly, for the better.

The academic year's sexism debate first arose during Convocation in September, when some members of the Women's Issues League—a feminist group on campus handed out flyers urging the crowd not to stand during the traditional singing of "Men of Dartmouth." As it turned out, only a handful of students sat; most stood despite, or perhaps because of, the women's efforts.

Feminist actions continued throughout the fall. Women's bathrooms were marked with militant feminist graffiti. Even "Women" signs on the doors were rubbed off—presumably because of their etymological offensiveness.

More incidents followed. Twice this year, members of the Women's Issues League obtained exaggeratedly explicit newsletters published by fraternities. The women copied the newsletters, passed them around campus, sent them to the trustees, and even distributed them during Freshman Parents Weekend. In response to one of the newsletters, which contained a cartoon of a brother having sex with a female pig, bloodied tampons were strewn across the offending fraternity's lawn.

On campus, it got to the point where everyone was tip-toeing around. We became overly sensitive about who might be listening to our conversations, and fearful of attacks on what we said. Our sense of humor seemed to have completely evaporated. Some women expressed concern that they could no longer approach a group of men involved in a heated discussion with-out stifling the conversation; men would appear afraid that the women could interpret their remarks as sexist.

The actions of the Women's Issues League and its splinter groups forced people into a defensive posture. Constructive discussion about sexism seemed hardly possible. Even worse, the radicals have given feminism a bad name. The majority of women are afraid of being placed in a category with the extremists, and so they avoid voicing their opinions at all. When women on campus are asked if they are feminists, they often reply, in tortured self-contradiction, "I believe in equality for women, but I'm not a feminist."

On the other hand, the radicals have, in the bluntest way possible, made a point: despite more than 15 years of coeducation, women do not yet feel integrated into the Dartmouth community. Everyone at the College has been forced to respond to the problem—a first step toward resolution.

One midnight in late April, for example, about 100 women and men marched peacefully around campus to protest sexism at the College. During spring term, students formed new groups that did not have the radical stigma of the Women's Issues League. Then in May, the Women's Support Task Force released its report, which recommended the creation of a resource center with specific guidelines to appeal to a broad section of the community—including men.

As the spring term ended, we sensed more listening and self-examination on sexism than had been evident at the beginning of the year. Women have begun to realize that they have choices other than that between radical feminism and silent acceptance of sexism. We learned that there is more than one definition of feminism, and of sexism.

Of course, it's still hard to tell a good joke without fear of offending someone, and the sexism debate has strained some friendships. But these difficulties are part of a process that the College badly needs to undertake. Call them growth pains.

Interns Lesley Barnes and Jock McDonald graduated in June.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

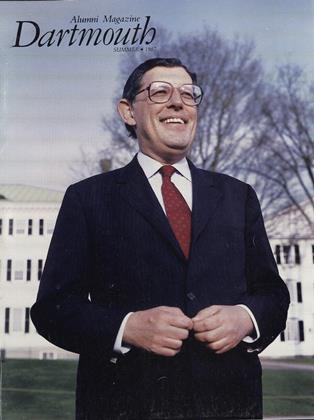

Cover Story

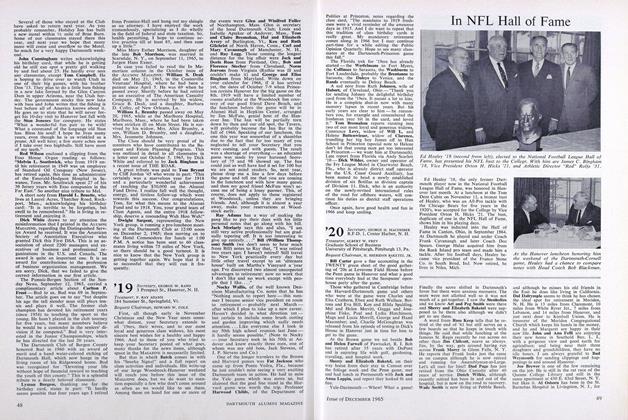

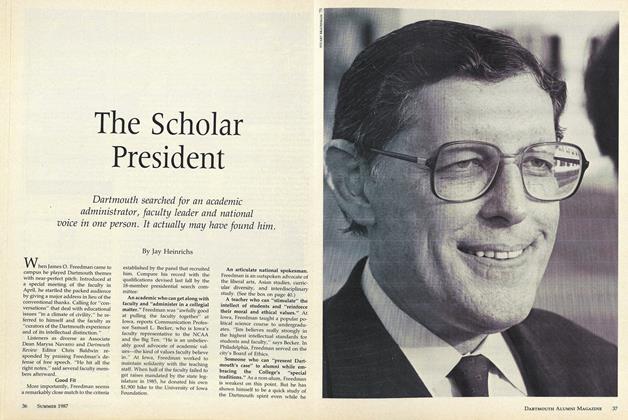

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

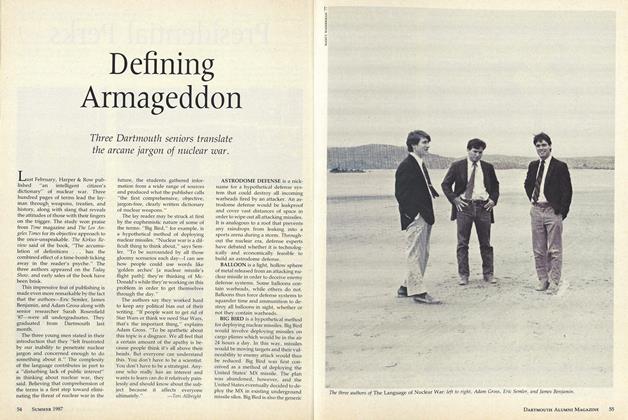

FeatureDefining Armageddon

June 1987 -

Feature

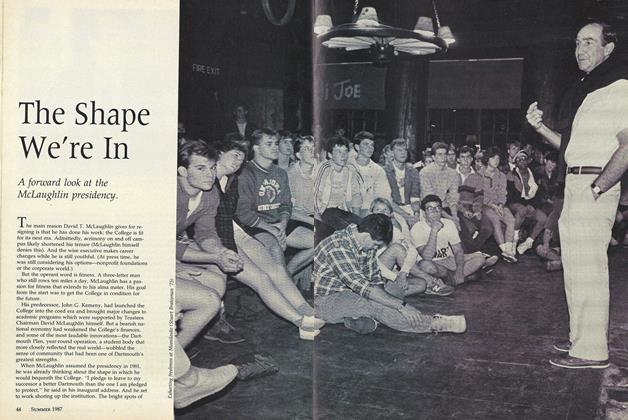

FeatureThe Shape We're In

June 1987 -

Feature

FeatureLife on Campus Is Slated for an Overhaul

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

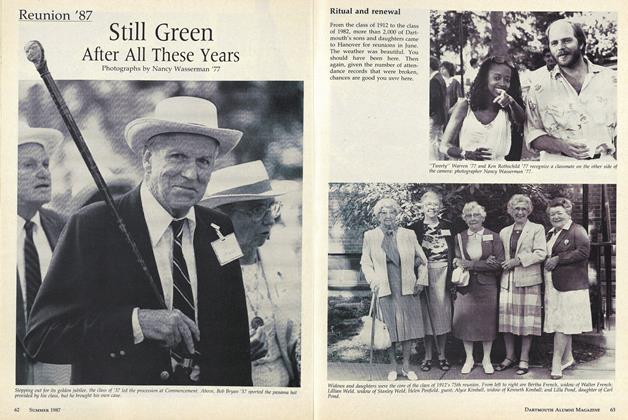

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987