Lewis Harriman Jr. may have been the oddest banker Buffalo has ever known. At the height of his career with Manufacturers & Trust Company, he had no staff except for one secretary, no conventional banking responsibilities and had never lent anyone a dime.

Although Harriman eventually became a vice president of the bank, he was on "special assignment," according to Manufacturers & Trust vice chairman of the board Frank Harding. Harriman playfully described his position at the bank as a "freefloating apex" in which he followed his own sense of community responsibility and reported only to the chairman of the board.

"There wasn't another person like him working for other banks, let alone any other local corporations," recalled Harding. "He was given free rein to do almost whatever he wanted."

For more than a quarter century, Harriman has been a kind of free-lance citizen, involving himself in issue after public issue, from education reform to race relations to urban planning.

Harriman was the first champion of the idea that Buffalo needed a rail transit line to connect downtown and the planned Amherst campus of the State University at Buffalo 12 miles away. It was also Harriman who organized, debated, cajoled, lobbied and politicked for his idea.

Harriman traces the story of rapid transit in Buffalo back to the early 1960s when plans were made to merge a financially troubled University of Buffalo into the state university system. A much larger campus for the new university of 26,160 students was to be located in Amherst.

"That's a city, man," he remembers telling himself 20 years ago. "And Buffalo's a city. And they're only 12 miles apart. There's got to be a corridor, justifying rail."

Harriman admits that he always wanted a rail system. Buses could move people but only a rail facility with the power to move lots of people quickly could also focus and magnify the economic development potential of the area—as had happened in Toronto. It was a far better choice than more highways.

"Cloverleafs of expressways destroy and scatter," Harriman said. "Subway stations attract investment and people and jobs and service."

It was a dozen years between the time that Harriman first floated the idea of a rail transit system in 1967 and the time that ground was finally broken, nearly two decades between conception and completion. Harriman was there nearly every step of the way, and though he has sometimes criticized the Niagara Frontier Transportation Authority for one thing or another, he seems to take criticism of the transit line itself almost personally.

"Why do I do this? I'm asking myself now since I've gone so far. And I'm just a banker on a pension. I'm a retired banker, not a capitalist at all. Why? I come from a long line of Episcopal ministers. I think there's something in my upbringing, maybe even in the genes," he quipped, "that seems to want to tell people what to do."

Harriman is particularly perturbed by the public attention attracted by the operating deficits of the line. Nearly every public transit system in the world operates at a deficite, he points out. But progressive governments gladly pay the subsidies because transportation makes their economies go. The Japanese, he noted, spend tens of billions of dollars a year to subsidize rail operations. He says, "We're carrying more people per car, per day than any light rail system in North America except Toronto."

"The people have to understand that this is a public service worth investing in," Harriman said. "You don't make profit on a school system. You invest in the youth for the future. (The Japanese) are investing in transportation for all of their people because it's good for their economy." His voice rises as he makes the point: "It's profitable."

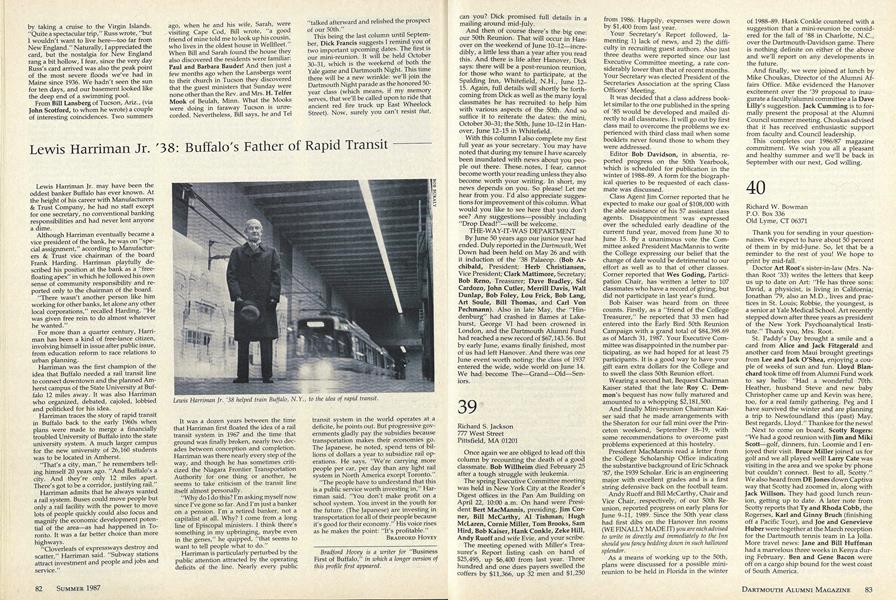

Lewis Harriman Jr. '38 helped train Buffalo, N.Y., to the idea of rapid transit

Bradford Hovey is a writer for "Business First of Buffalo," in which a longer version of this profile first appeared.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureThe President's In-box

June 1987 By JAMES O. FREEDMAN -

Feature

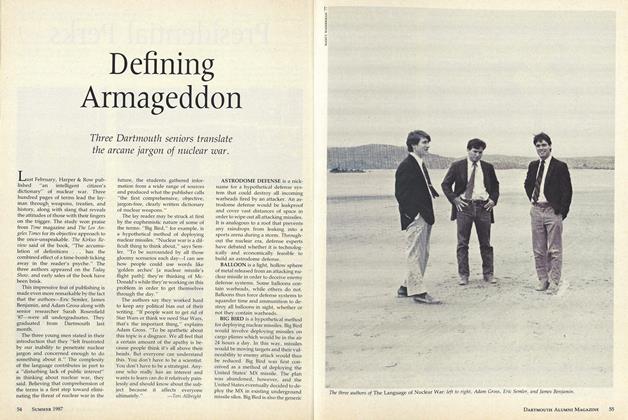

FeatureDefining Armageddon

June 1987 -

Feature

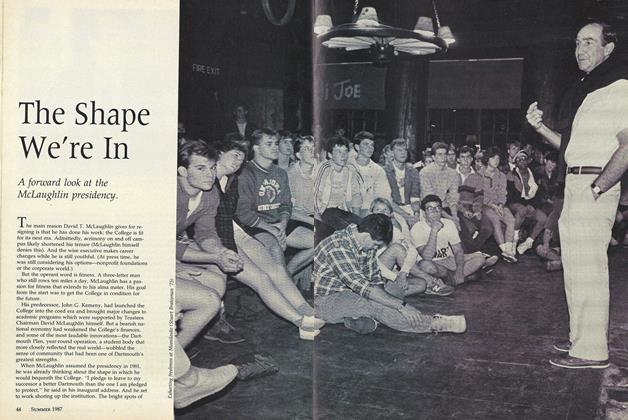

FeatureThe Shape We're In

June 1987 -

Feature

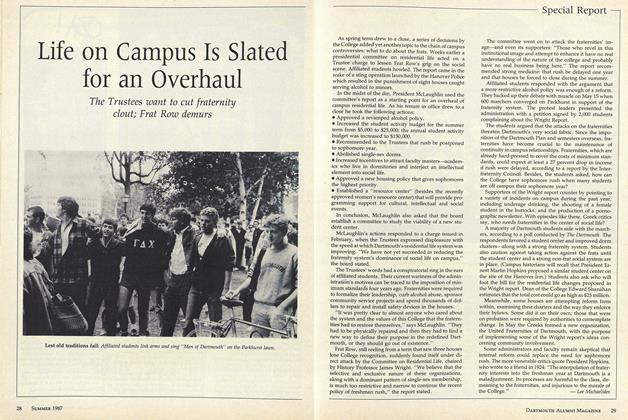

FeatureLife on Campus Is Slated for an Overhaul

June 1987 By Lee Michaelides -

Feature

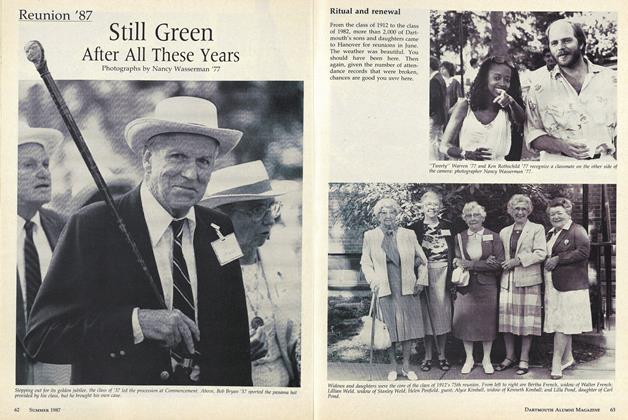

FeatureStill Green After All These Years

June 1987

Article

-

Article

ArticleMILESTONES

June 1935 -

Article

ArticleJAMES F. ROOT (above, right, with Coach Bob

FEBRUARY 1964 -

Article

Article'42 Gift Aids Teaching

JANUARY 1972 -

Article

ArticleGeorgia

OCTOBER 1962 By C. ROBERT FELTMAN ’55 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER BROWSING

December 1935 By Herbert F. West '22 -

Article

ArticleAN ERROR CORRECTED

November, 1912 By JOSEPH W. GANNON