The man behind the plan.

THERE ARE THOSE IN ACADEMIA who go into mourning whenever a top faculty member goes over to the administration. But when Thayer School Professor John Strohbehn became provost in 1988, Dartmouth didn't lose an engineer, it gained a troubleshooter. "Engineers are problem solvers, and a lot of what I do now is solve problems or at least try to solve more problems than I create," says Strohbehn. The Stanford-educated professor has been at Dartmouth since 1963, where he gained an international reputation in biomedical engineering. Between teaching classes, he worked with other researchers in the Thayer laboratories to refine a technique called hyperthermia, in which microwave radiation "cooks" cancerous tumors.

He still advises three Ph.D. students who are willing to meet with him at the ungodly (for students) hour of 7:00 a.m. He keeps up with research in his fields. And he takes off lunch most days to go biking or to ran with colleagues on a six-anda-half-mile route along the Con- necticut. But he spends most of his 12 -hour day overseeing Dartmouth's academic programs from Arts & Sciences to the Hopkins Centerand keeping Dartmouth's planning going. "Dartmouth needs a more structured process," he says. "You should never stop planning."

Phase one in that effort was the College-wide Planning Steering Committee report, a job that involved more than 70 people and took almost two years. Strohbehn warns readers of the report not to expect a master plan. "It's not real specific," he admits. "We didn't get into saying Dartmouth should definitively go in this direction or that one. And we certainly didn't say that Dartmouth should not do anything in particular."

He also admits that the plan would be difficult to carry out without those decisions about what not to do. "The PSC report didn't square finances with goals. But it sets us up for the next step: financial planning," he says.

One definite result is a series of departmental reviews to be carried out over the long term by peers from other institutions; the provost will oversee the program. And a likely result will be the expansion of a few select graduate programs. Will that make Dartmouth more like Harvard?

"We're not arguing for graduate studies in the humanities or social sciences," he replies. "We'll probably stick in programs almost exclusively in the sciences.

"And any improvement in those programs doesn't mean you have to let the undergraduate programs suffer. Undergraduate students in the sciences think graduate programs are a plus. They give them opportunities they wouldn't have otherwise.

"My own project is an example: the year before I became provost, I taught a junior-level course, and used practical examples from my own research. Two students ended up working with the project their junior summer. Both of them went on to do undergraduate research and became part of the project team. And one of them published his undergraduate thesis in an international journal. So the team became a continuum, from undergraduate to graduate student to senior professor.

"So, no," he concludes. "The PSC report would not bring us any closer to Harvard. Perhaps it will bring even more quality to the undergraduates."

Strohbehn doesn't like to back-pedal.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

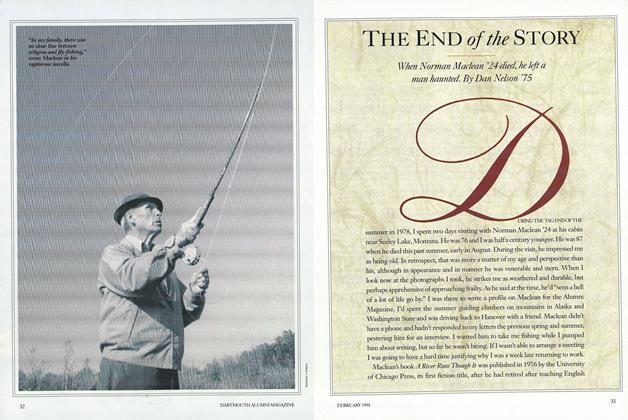

FeatureThe End of The Story

February 1991 By Dan Nelson '75 -

Feature

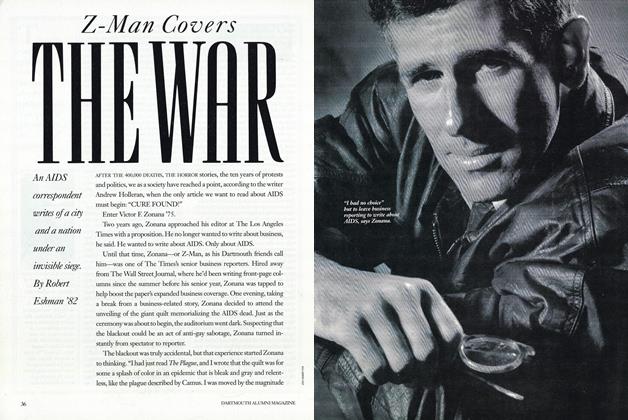

FeatureZ-Man Covers The War

February 1991 By Robert Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureOUR PASSIONATE PREFERENCE

February 1991 By Joseph D. Mathewson '55 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryNow For The Hard Part

February 1991 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWHO OWNS DARTMOUTH?

February 1991 By Joe Boldt '32 -

Feature

FeatureIs Harvard Becoming More Like Dartmouth?

February 1991

Jay Heinrichs

-

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

MAY • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureRising Sophomore

June • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleOut of the Woods

NOVEMBER 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

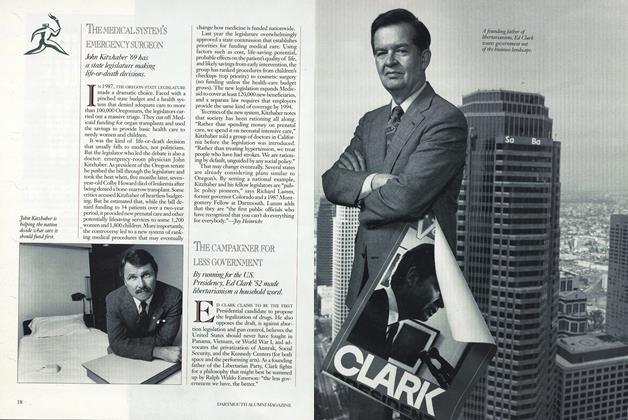

Cover StoryTHE MEDICAL SYSTEM’S EMERGENCY SURGEON

JUNE 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Cross Section of Existence

MARCH 1992 By Jay Heinrichs