Making Tracks

After a decade in a warmer climate, I met the snow forcefully this past January. That was when I first noticed a subtle change in the nature of cross-country trails that appears to be affecting the entire north country.

Just as winter began, my daily office commute switched from an hour on the Washi ngton Beltway to an hour on the machinegroomed cross-country ski trails of the Hanover Country Club _ counting time spent on irresistible detours. It didn't take me long to get acclimated; my daily route now goes through a spectacular new 30-kilometer trail complex maintained by the College.

A week or so into the new year, a foot of snow fell onto a half-foot base, and on Sunday we awoke to the season's best skiing. "Sorry," I told my wife, "I've got to put in a few hours at the office. It's the nature of a new job." And, with a small twinge of guilt, I donned Nordic skis and headed from our apartment on Reservoir Road down to the Connecticut River the most roundabout way possible to ski to campus.

Halfway to the river I saw the change that had come over the snow: the trail hooked up with a wide path, and the parallel tracks disappeared in an anarchistic jumble of slash marks and pole holes. This disturbed me greatly, because I had come to find satisfaction in a well-tracked Nordic trail that cuts through field and woods in what Frost would call "a momentary stay of confusion." One's skis faithfully follow the tracks, with only an occasional interruption for a steep hill. I write as an expert on snow, owing to my status as an inept skier. A skier who falls frequently, and keeps an open mind while doing it, learns things about the snow that the expert has forgotten. A good skier rarely feels the soft nihilism of a fresh snowbank, or the no-nonsense abrasion of an iced-up trail. On the other hand, a properly inept skier one who meets the snow head-on, opening his mouth in surprise as he falls is much more discerning about the stuff he lands in; he becomes something of a snow gourmet.

While quietly congratulating myself on my lack of prowess, I caught the edge of my ski on a herringbone and suddenly tasted snow (dry texture, good loft, and a piquant bouquet that hinted of road salt). Pulling my head out of the snowbank, I was startled to see heading toward me a phalanx of brightly clad skiers. Obviously competing in a race, they were propelling themselves with a strange, limping style that emphasized poles and hips.

I had seen the technique; called skating, for years. In the old days, skiers did it when there were no tracks, and they were on a flat surface, and they wanted to look snappy. But most of the time, one skied by throwing one's shoulder forward and hoping that the rest of the body followed before the opposite ski skidded backward. Done properly, the old technique looked like an exaggerated form of running.

The amazing thing about these fast-approaching skiers was that they were skatinguphill not just herringboning or running with quick little steps, but gliding as if gravity were nothing but a fading tradition. I was forced to roll back into the snowbank to avoid a collision. The competitors scuttled up the incline like deft crabs, sashaying their hips in second-skin space fabrics.

I took mental notes as the skiers whizzed by, and then triec} the technique on skis that suddenly seemed impossibly long. As far as I can tell, the trick of skating uphill requires performing the following steps all at the same time: plant one ski at a 165-degree angle, tip facing outward. Also plant both poles while lifting the unplanted ski in a careless gesture. Using all your strength, shove with the poles and the planted ski. Do all of this unconsciously, but take care that your poles are outside your skis or you will find yourself face-down on the trail (sticky texture, with a faint ripple of blue wax).

Those who fail to make the transition to skating risk showing their age. Good young skiers skate; good old skiers throw their shoulders forward in a fit of obsolescence. The College does oblige the obsolete skier by diligently replacing skatec}-on trails with clean, fresh tracks. But they are all too quickly erased by the new skiers. There is nothing for it but to adapt, and risk a violent intimacy with the snow (faint smell of pine, texture of snowplow effluvia . . .).

Jay Heinrichs became editor of this magazine lastDecember.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

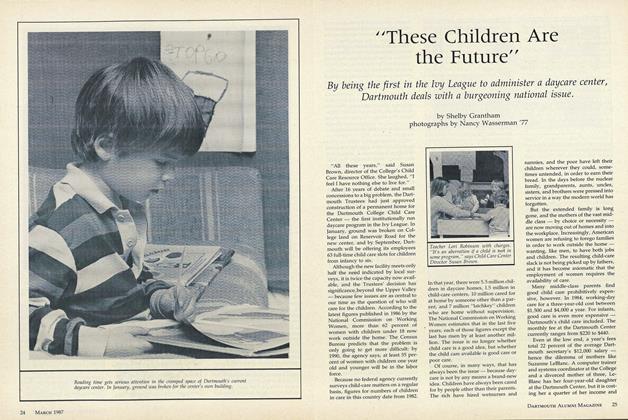

Feature"These Children Are the Future"

March 1987 By Shelby Grantham -

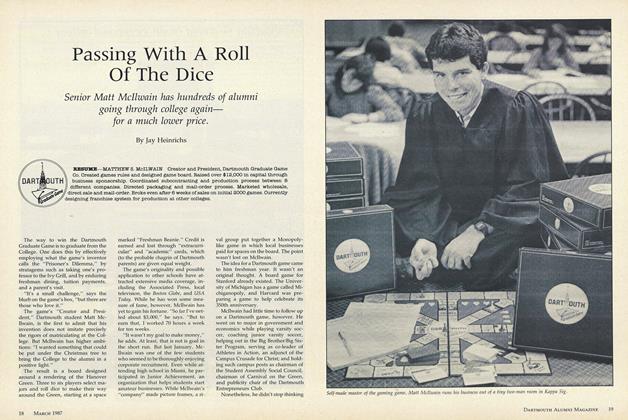

Cover Story

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

March 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

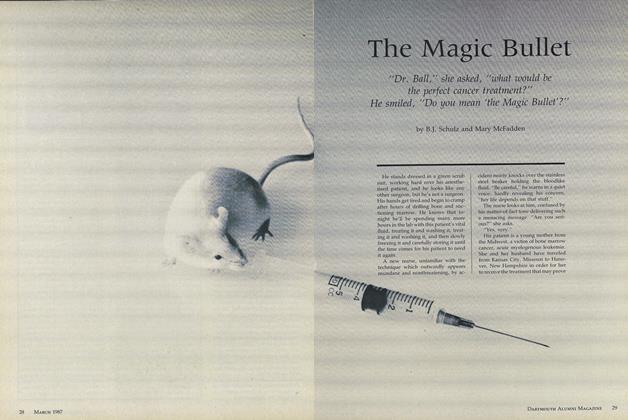

Feature

FeatureThe Magic Bullet

March 1987 By B.J. Schulz arid Mary McFadden -

Feature

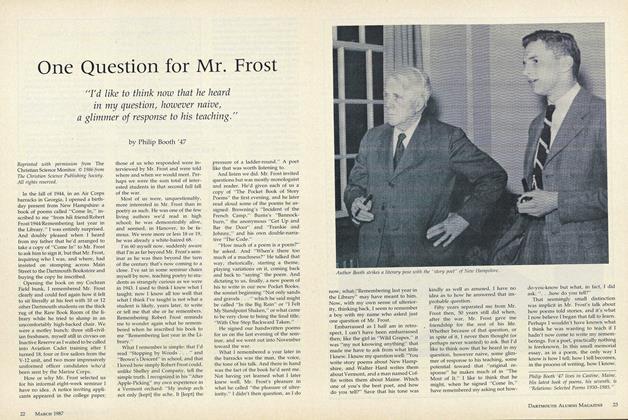

FeatureOne Question for Mr. Frost

March 1987 By Philip Booth '47 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

March 1987 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

March 1987 By Ken Johnson

Jay Heinrichs

-

Cover Story

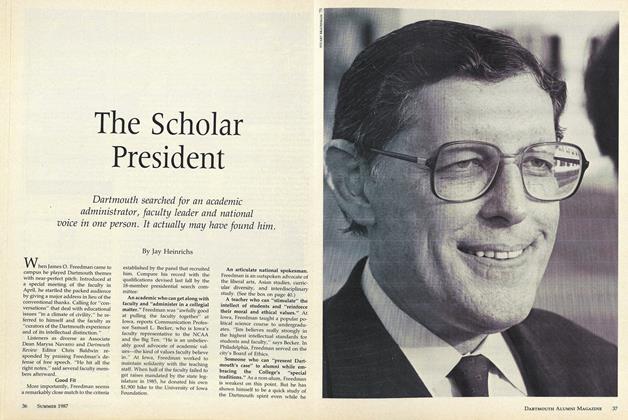

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryA Cross Section of Existence

MARCH 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleBeyond Scrapbook

May 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

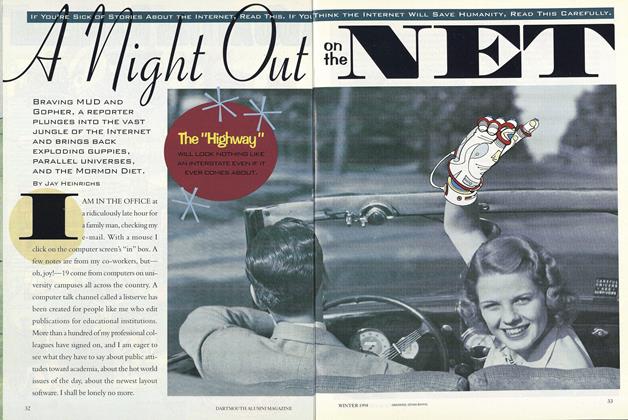

Cover StoryA Night Out on the Net

December 1994 By Jay Heinrichs

Article

-

Article

ArticleMANAGERIAL INSIGNIA

December, 1914 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH DRAMATICS OBTAIN SERVICES OF NEW COACH

November 1923 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth's Goals and Purposes

JUNE 1973 -

Article

ArticleHANOVER UNDER COVER

FEBRUARY 1964 By ALLEN R. FOLEY '20 -

Article

ArticleThe Tuck Alumni

May 1945 By Herluf F. Olsen '22 -

Article

ArticleHearts and Minds Study

May 1979 By TIM TAYLOR