A high-tech climbing novice seeks to prove that Sir George Mallory was the first to reach the summit of Everest.

I low DO you explain the itch to temporarily give up family and job to climb on Mount Everest and look for a 62-year-old fold-up camera the size of a paperback book? Tom Holzel explains it like this: "Although I'm normal in most ways, I am rather obsessed by the mystery of Mallory and Irvine."

When pressed for further explanation, Holzel turns around Sir George Mallory's famous quote: "Because it is there." And then the 46-year-old Dartmouth grad elaborates. "Essentially I got involved because I thought it was a wonderful mystery that could still be solved." The question of whether George Leigh Mallory and Andrew Comyn Irvine reached the top of Mt. Everest in 1924 before they died on the mountain was more than academic for Holzel, because in mountaineering, he believes, "the first ascent is credited to climbers whether or not they return alive. If Mallory and Irvine were indeed the first to reach the top, their success would unseat Sir Edmund Hillary and Sherpa Tensing Norgay's record, who were certainly the first to reach the top and come down alive."

Holzel is not an adventurer by vocation. He is the chief executive officer of Arcturus, Inc., an engineering firm located in Acton, Massachusetts, that makes big-screen computer displays. When he came across Mallory and Irvine in a New Yorker article in 1970, Holzel had never climbed a mountain. He went to the library and read everything he could find about the two explorers and their ill-fated attempt to scale the world's highest mountain.

Years of research resulted in Holzel's prediction that "Mallory or Irvine is up there on a snow terrace at 27,000 feet. As each climber was known to have carried a camera," he adds, "that camera should be perfectly preserved on the frozen mountain." The film might still hold undeveloped pictures. And those pictures might prove whether the men reached the top before they died.

Holzel decided to climb the mountain and find the camera. Along the way, he and the people he infected with his ideas turned to technology to overcome some of the foreseeable problems. For instance: how do you locate a very little camera on a very big mountain? How do you breathe while you're looking for it? How do you develop a film that's been frozen for half a century? They found, or so they thought, answers to these questions.

What their ingenuity and planning didn't conquer, however, were two challenges of humankind and nature-the problems of shipping tons of gear halfway around the world, and the very things that made Everest such a seductive symbol for Mallory and all the rest: its awful weather, its vicious winds, the sheer size of the mountain.

Given the altitude and the relatively crude climbing gear available to the two Englishmen, is it realistic to think that the men could have made it, 29 years before Hillary? Holzel's years of research, calculating, reading maps, and interviewing the men's friends and the expedition's survivors convinced him that it was possible. (He describes his historical sleuthing in First on Everest: The Mystery of Malloryand Irvine, a book he coauthored with historian Audrey Salkeld.)

Holzel calculates that at the time Irvine and Mallory were last seen, each had about an hour and a half of oxygen left for a three-hour trip to the summit. Holzel suggests that, given Mallory's obsession to succeed, he would have hit upon the idea of combining Irvine's remaining supply with his own and striking out for the top. Holzel says he is almost certain that Irvine's body is still on a snow terrace at about 27,000 feet, and he knows a reasonable place to look for Mallory's, too. A Japanese report of a body discovered at that elevation inspired Holzel to apply for permission to climb Mt. Everest from the Tibetan side via the Mallory route.

"Most people didn't believe there was anything on the terrace," Holzel says. "But I have lost things in the most improbable places and gone back for them. They are always there. If you look, you'll find it. I said, 'lt's got to be there.' There's no action on the North Face of Everest that will take something away. There are no avalanches. The snow builds up, but it never consolidates, because it's too cold. It blows away. So I was convinced, although no one else was, not only that there was a body there, but that we could go look for it." If there is a body, he reasoned, there should also be a camera. Even if the body were covered with snow, the camera might still be found.

He went to a company that makes metal detectors. It offered several standard designs, none of which seemed quite right. So Holzel sent the company exactly what he was looking foran old Vest Pocket Kodak just like Mallory and Irvine's. The firm put together a metal detector that was tuned to sense just such an item, a small, shallowly buried object made of brass and aluminum.

When Holzel began planning in earnest, the first problem was whether the camera's film, after all these years, could still prove anything. "If I found the camera, would it do any good?" he asked. "Who wants to spend a fortune going to Everest, risking your life, and then, so what? You've got an old camera."

That began a long correspondence with Eastman Kodak in Rochester, New York. Kodak engineers said the film, frozen all those years, should still be in good shape. They cautioned that if it thawed, the images would be lost within a few days. Holzel should be prepared to process the film on the mountain, using a mixture of modern developing chemicals and defogging tablets. He took the engineers' advice and packed a portable developing kit.

However, a few months before the expedition was set to leave, Kodak tried out its advice on some 50-year old film. "It didn't work," Holzel was dismayed to learn. "Nothing. Zero." The Kodak people went back to the lab and concocted a new formulation that would work on this kind of old film.

But there was still another concern. Sitting at 27,000 feet in the thin reaches of the Earth's atmosphere, the camera would be blasted with cosmic rays that might have damaged the film. Later tests showed that film this slow suffered relatively minor harm, however. The final plan was to keep the film cool and return the film to Rochester for processing.

While high altitudes are bad for film, they are damaging to people as well. Such heights, with their scarcity of oxygen, are extremely taxing on the body. Muscle output is diminished, the sense of balance is affected, sleep is light and unrefreshing, and food is poorly metabolized. Simple tasks like pulling on boots become difficult, and climbers must move with painful slowness. They also risk a dangerous condition known as acute mountain sickness, in which fluid builds up in the lungs and the brain, causing rapid incapacitation and death. "I did not want to prove that man was superior to the mountain," says Holzel. "I realized I myself would have to use oxygen. I knew that what was available was okay but not great. At 46 years of age, what could I do to cheat?"

The breathing gear routinely used by mountaineers is called an open-circuit system. Climbers breathe outside air, and a little carburetor-like affair enriches it by metering out squirts from big tanks of pure oxygen. At 27,000 feet, Holzel explains, the apparatus makes the trekker feel as though he is at 20,000 feet. "It's not much of a lift," he says. "It's better than nothing, and often it's the difference between success and failure. However, if you were to breathe pure oxygen, you effectively would be put back down to sea level."

Such an approach—breathing the pure gas without any outside air—is called a closed-circuit system. It raises many technical problems. A climber's lungs ventilate at a rate of about 50 to 100 liters of air each minute, but he burns up only 3 or 4 liters of oxygen. It would be wasteful to breath in pure oxygen and then exhale the unburned oxygen that has passed through the lungs. Instead, it must be rebreathed until it is completely absorbed in the bloodstream.

But every time a climber breathes out excess oxygen, he also breathes out carbon dioxide. Unless the carbon dioxide is filtered out, it will build up in the lungs. Such an excess of CO2 triggers the breathing reflex. Rebreathing carbon dioxide would make climbers pant so desperately they would be brought to a standstill.

Oxygen in favor of a granular chemical called potassium superoxide. When the climber's moist breath passes over this chemical in a canister, a bit of oxygen is released—precisely the amount, in fact, that was removed from the previous lungful. But just as mportant, the chemical absorbs carbon dioxide. Holzel therefore eschewed pure

Holzel found such a system already in use by rescuers in mine disasters. He tested it inside a Army cold chamber. It worked fine until he stopped to change chemical canisters. During the one minute changeover, the whole system froze solid. The problem, Holzel saw, was that the model he used was made of metal, which made the system retain all the moisture of breathing. There was no way to eliminate the moisture, so he designed, and eventually patented, a new version that would stand up to freezing. "What I did was make the whole thing out of rubber," he said. "And I made it in such a way that whenever it froze, I could manipulate and crush the frost so that it would fall into an out-of-the- way spot that I could clean later in the day."

Finally, after four years of negotiations with the Chinese, Holzel obtained a permit to mount an expeditioto Everest via the Mallory Route. Andrew Harvard '71 organized and led the expedition. Harvard, a lawyer with the Federal Reserve Bank in New York, was planning an Everest trip to make a film about the mountain's early climbers, including Mallory and Irvine; the two projects fit nicely.

The 30-member party intended to assault the mountain during the brief period between summer monsoons and winter storms when the weather is most hospitable. But Holzel's technology suffered a serious blow before the group even got to the mountain. He had shipped 96 canisters of chemical oxygen for use in his newly designed equipment. It never arrived. Somehow, it became enmeshed in a shipping mixup and still sits, so far as anyone knows, in a customs warehouse in Delhi. Most of the expedition had to resort to conventional open-circuit breathing equipment.

Holzel did, however, ship three extra canisters in his personal equipment. Two he gave to another expedition member, who used them while climbing and found that they worked well. The other one Holzel strapped on one night as he went to bed at 21,000 feet. "I went into a comatose sleep," he remembers. "I literally blacked out. I was just enormously refreshed by it."

The expedition itself did not go as well. Frequent snow and wild winds made avalanches a constant risk. Holzel never got above 21,000 feet, whilsome other members of the climbing party got as high as 25,300 feet. On the day when Holzel was supposed to go to 23,000 feet, a Sherpa coming down the mountain was caught in a snow slide and killed. "There was always the knowledge that it was risky climbing there," Holzel said. "But by the time the Sherpa died, conditions had deteriorated so that people didn't want to go up anymore." The goal became getting down the people who were still on the mountain.

Even though the climbers never got high enough to look for cameras, Andrew Harvard says that Holzel's new breathing apparatus may be a lasting benefit of the expedition, although it still needs to be tested in the high mountains. "From a climber's point of view, it's right at that stage where really good field testing may lead to refinements that will make it a workable system," Harvard says. "I think it has the potential to be a useful climbing oxygen system and, more significantly, a reliable emergency oxygen system for the mountains."

For his part, Holzel hopes that other climbers will take up the search for the old cameras. He has no plans to return, but he is satisfied with having made the effort. "It was the thrill of a lifetime," he says. "I knew that there was a better than 50-50 chance that I wouldn't get up there. I wanted to take a shot."

Does he consider the trip a failure? "What's failure?" he replies. "Failure is not trying."

High-altitude archaeologist: Holzel, pictured at 21,000 ft., sits with his customdesigned metal detector. Bad weather kept him from the spot where he expected to locateMallory's camera.

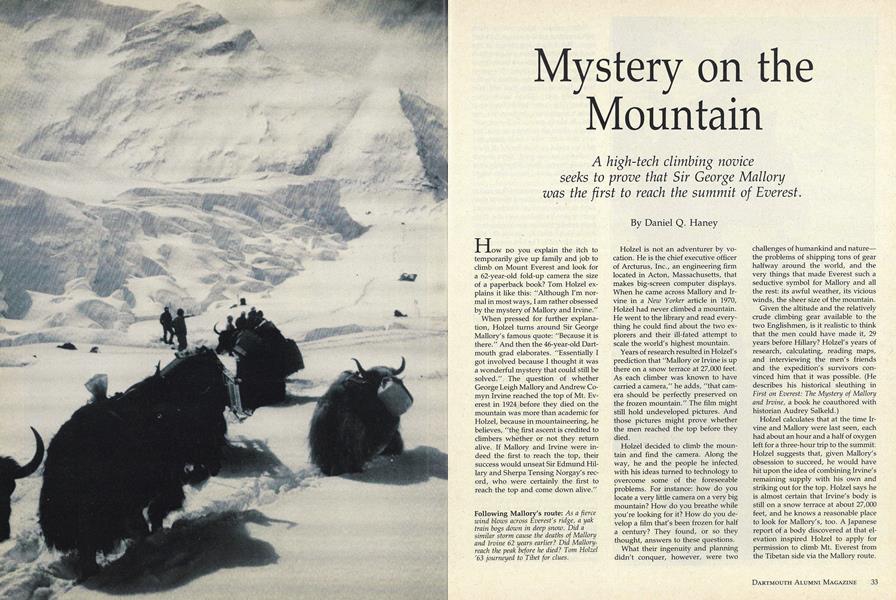

Following Mallory's route: As a fiercewind blows across Everest's ridge, a yaktrain bogs down in deep snow. Did asimilar storm cause the deaths of Malloryand Irvine 62 years earlier? Did Malloryreach the -peak before he died? Tom Holzel'63 journeyed to Tibet for clues.

Better breathing: Holzel displays hischemical oxygen system. Proper fieldtesting was impossible because thecanisters of chemical oxygen got only asfar as Delhi.

Daniel Q. Haney is a writer with the Associated Press in Boston.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureDiary of a Long Distance Runner

September 1987 By Tim Hartigan '87 -

Cover Story

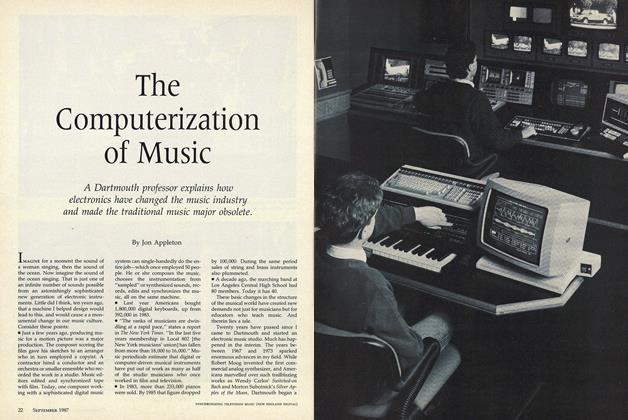

Cover StoryThe Computerization of Music

September 1987 By Jon Appleton -

Feature

FeatureThe Speech

September 1987 -

Feature

FeatureHeeding the Beat of a Different Drummer

September 1987 By Teri Allbright -

Class Notes

Class Notes1976

September 1987 By Martha Hennessey -

Class Notes

Class Notes1983

September 1987 By Kenneth M. Johnson

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCharles Faulkner Professor of Patholog! 10,000 feet in a single wing

January 1975 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryFred H. Brown 1903

NOVEMBER 1990 -

Feature

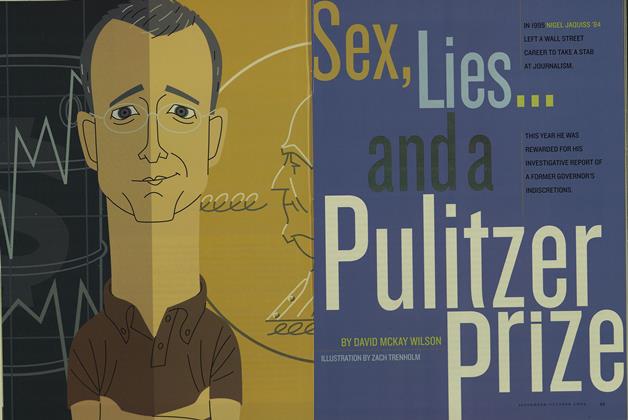

FeatureSex, Lies... and a Pulitzer Prize

Sept/Oct 2005 By DAVID MCKAY WILSON -

Features

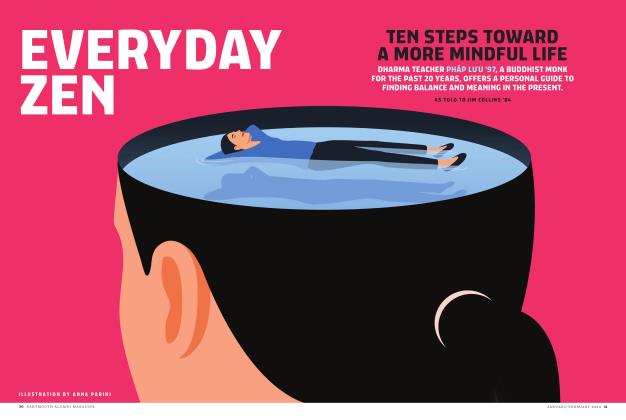

FeaturesEveryday Zen

JANUARY | FEBRUARY 2024 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

FeatureLiberal Arts, yes 'Core of Knowledge,' no Changing the Calendar, maybe

JAN./FEB. 1980 By Mary Ross -

Feature

FeatureThe Disinterested Citizen and the Maintenance of Freedom

July 1960 By WHITNEY NORTH SEYMOUR, LL.D. '60