Some thoughts on America's chief metaphor for life.

The act of kicking a field goal tends to concentrate things. One game can affect a career, one play can determine a game, the play depends on the 1.27 seconds in which the kicker is in motion, and the motion comes down to the four milliseconds during which the kicker's foot is in contact with the ball.

Take the second game of the 1986 season. It was a Thursday night game against the L.A. Raiders, our hated rival. O.J. Simpson, Frank Gifford and Joe Namath were doing the broadcast on ABC. I was having a good night, hammering my first three field goals from 38, 22 and 42 yards. Still, the Raiders led 14 to 9 just before halftime. With a minute and a half left, we got the ball and drove it halfway down the field. Suddenly it was fourth down with the ball just inside the 41-yard line, sitting right in the middle of the "AFC" logo. The coaches' decision: to attempt a 58-yard field goal. My moment in the lights 1.27 seconds compressed into four milliseconds—would be watched by 80,000 people in the stands and 47 million more people over network television.

People often say that football is a metaphor for existence, which is true. Football is life, with rules. The goals are literal; you make them or you don't. If football is an orderly distillation of life, then kicking is a distillation of football. The goal is in front of you, and you either get the ball through it or you don't. Success or failure is compressed into four milliseconds.

But this isn't a story about football; at least, not entirely. This is a story about Ivy League education. Keep that in mind; I'll get to it later.

Whether you make the goal is determined in large part by what happens before and after the kick—what you do when your foot isn't touching the ball at all. It is the Zen approach to football: remove all the obstacles to the goal, physical and otherwise.

Obstacle: giant defenders. The physical barriers are hard to miss. Even before the holder has caught the ball, 11 people are running after you, all of them amazingly tall and quick enough to cover 40 yards in less than five seconds. Their job is to be physical obstacles. One of the best is Chicago's Dan Hampton. During kicking play he comes in behind the Refrigerator, William Perry, a 350 pound defensive lineman. The Refrigerator's job is to crush your team's center while staying very low, almost on his knees. Over him flies Hampton, who is six foot six. When he leaps into the air to block your kick his hands form an 11 - foot-high barrier. You have 1.27 seconds to get the ball past Hampton and between the goal posts. Sometimes you fail; I have had one kick blocked—while playing Chicago.

Obstacle: pressure. Most impediments are in your head, and there are a variety of ways to get rid of them. I know a kicker who drowned them. He would deal with the pressure before a game by drinking a sixpack and downing several shots of whiskey. It was an exhausting regimen, but he played for close to 15 years. I won't tell you who he was, though.

My methods are a little less risky. For me, the instant of kicking climaxes years of intensive preparation involving, among other things, a sports psychologist, numerous coaches, weight training, running, stretching, ballet lessons, aerobics - even acting classes and a Dartmouth education. The Ivy League: I'm getting ahead of myself again.

Obstacle: failure. The mental obstacles are the worst. One of the first a pro ball player often faces is ego damage. Before signing with Kansas City I was cut by the New England Patriots, New York Jets, Baltimore Colts, New Orleans Saints, San Diego Chargers, Cincinnati Bengals, and Washington Redskins. Even at the time, though, I was able to see that being cut had its healthy side. It prepared me incrementally for the life of the professional football player—for life on the sidelines, for huge men who wanted to smother me into oblivion, for the pressure of playing for money, for getting over the fear of failure and, mostly, for the experience of failure itself. This is something we must all learn to deal with if we are to be truly "successful."

Obstacle: the last kick. Part of what separates the good kickers from the bad is the ability to recover from the previous field goal. At Dartmouth, whether I made a kick or not, I was still a part of the team. But in the pros, they don't want you on the team if you aren't going to put the ball through the goal posts every time. Missing a kick can affect your career. Last year I missed four out of 23. Two of the misses were from 49 yards—long shots that just didn't make it. One kick, the one in Chicago, was blocked after a delayed snap. And one against Denver, which I should have made, I missed. That one kick makes me wish to God I had the game to play over. In the games before Denver I had made seven straight field goals. It was a very good year, but you remember the mistakes.

Obstacle: distraction. In one sense the pros are easier than college was. At Dartmouth, the coaches were true to their word: the priority was academics. My courses made it difficult to think much about a game until the night before. In the pros, the night following a game I'm already thinking about the next one. Like many athletes, I play the sport in my head. More importantly, I create a unique emotional background every week. It is said of Meryl Streep that she is so totally committed to the characters she plays that she becomes them; that is how she is able to play so many utterly different parts. In some small way I try to do that myself—to become committed to each game just as the actress is committed to her characters. If you can find meaning in each competition, you can rise above the merely good. An example is that Thursday night game against Los Angeles. My theme for the week was respect. The Raiders had beaten us consistently for the past several years, and they seemed to scorn us. I wanted to help win what was due us. You'll see the results a little later.

My mental preparation is aided by Dr. Andy Jacobs, a sports psychologist who also works with the U.S. Olympic cycling team. I see him once a week for a half-hour or so. The sessions have nothing to do with transactional analysis or hypnosis; the point is simply to deal with the weekly issues that everyone has to deal with. Often we talk of nothing but my personal life. If you feel on top of all the aspects of daily existence — family, colleagues, bosses, yourself—then it is possible to direct your energy a hundred times more efficiently. In short, you're going to play well. Last year, for that reason, I went out to Los Angeles and took acting classes. It's a good release; it gets you in touch with your instincts

Obstacle: my own body, or rather its limitations. One of the most useful of Dartmouth's contributions to my football career was a ballet class I took during the summer before my junior year. The class met twice a week in Webster Hall, where we concentrated on balance and flexibility, stretching the hips and the hamstrings. The class hurt. It was physically painful, and I felt clumsy. But that awkwardness showed me the degree to which I could improve the amount I could stretch my body's limits.

Suddenly I knew what I was doing physically. For the first time my newly flexible body wasn't dragging the left leg as I approached the ball. That season I was 28 for 28 on extra points, and eight for eight on field goals, including a 51-yarder against Harvard. I still take a ballet class at least once a month. I also do aerobics, which in many ways is a takeoff from ballet. Just keeping my damn heel on the ground during a plie can be agony, but it brings results on the field.

Flexibility is key. A kick is like cracking a whip; the leg must swing and snap with perfect timing and explosiveness. I start stretching two hours before a game, and continue for the three hours and 20 minutes of play. I punctuate the stretching with an average of some 200 practice kicks into a sideline net. And then, of course, there are the kickoffs, field goals and extra points during the game itself. It helps to have my body ready.

Preparation determines a career. Professionalism in banking or lawyering or surgery or football means marshalling all your forces to produce consistently, to come through when needed. The true professional has a mental checklist for everything in his life. Will this help me meet the goal? Will it help me improve?

Athletes call this focusing: the art of concentrating one's life on a task. An ability to focus, it seems to me, is one of the benefits of an Ivy League education, or at least a liberal arts degree. Dartmouth gave me the discipline to improve, to concentrate, to maximize my potential. It taught me critical thinking, a way to analyze myself and my mistakes. It taught me to exhaust all the possibilities in achieving a goal. In short, it taught me to focus.

This concentration helps in my mental approach to the game. Jake Crouthamel, who was head coach when I played football for Dartmouth, used to say that details are everything. Take care of the little details and the big ones, like the wind, or six-six linemen, would take care of themselves. The more you can put down on paper, the more you can absolutely understand the kick, the better the kick. If that isn't the point of liberal arts, I don't know what is.

A single field goal involves a welter of detail. The 58-yard attempt against L.A., for example: after the coaches decided on a field goal, we called a time out. Most teams think they can psych out a kicker by calling time, but for me, the extra time helps.

So instead of standing out in the middle of the field in front of the crowd, I run to the sidelines and kick a couple into the net. I have more time to pick out the wind, which happens to be swirling from left to right in the stadium. "This is my chance," I coach myself. "It's my turn."

I pace eight yards back from the scrimmage line and stare at the minute spot of turf where the ball will be held for me after the snap. My adrenalin is up. Some people say they don't hear anything the roar of the crowd, the quarterback's signals— but I hear everything. I feel like an enormous sensory computer that can process the whole stadium.

I look at the spot on the ground and pace exactly four more yards behind the ball. Bill Kenney, our quarterback and my trusted holder, is on his knees with his left hand exactly on the spot, one square centimeter in size, where the ball will go. I look up at the goal posts and judge the wind, which changes slightly every ten yards. I decide to aim just inside the left upright; the ball will probably travel a bit to the right. There is a sign with a small "w" in the upperdeck seats. The bottom of that letter, which is the exact target, becomes imprinted in my mental vision. My eyes go back to the spot on the ground where the ball will go. I look at the spot and visualize the target.

Bill looks back at me. "Are you ready?" he yells. Usually he doesn't say anything. I nod, and he goes "Set" to the offensive line, and then the ball snaps and everything seems to slow down.

I'm still staring at the crucial spot where the ball will sit. As soon as I see it move in the corner of my eye, I start forward: a quick jab step with my left foot, a medium step with my right, and then the left plant step, the long stride that will create 85 percent of the kick's power. My left foot lands ten inches from the spot on the ground. All of this happens while the ball is in flight from the center's hands to the holder. The ball is set while right foot is swinging, toe pointed toward the target. My shoulders and hips are square, head down, right foot travelling toward the ball.

A fighter pilot trains to carry out half a dozen tasks in an instant; the details are so ingrained that he carries them out as an instantaneous whole. The same for me.

I'm not the only one with a job to do, though. Mike Haynes, an all-pro defensive back for the Raiders, runs around the right end and launches himself into the air, arms over his head. But he is a couple hundredths of a second late; I get the ball off faster than usual. Like a golfer's wedge, my right foot slices down into the leather, hooking the ball slightly so that it heads toward the left upright. The wind does its part, drifting the ball back toward the right and putting it precisely in the middle of the uprights. As the ball clears the goal by an extravagant ten yards, the stadium begins to roar. It is now 14 to 12, and the psychological lift will help us go on and win the game.

Bill and I begin running off the field when Bill looks back and sees Mike Haynes standing stock still, staring at the goal posts. "Are you all right?" Bill calls to him. He just stands there, dumbfounded, staring at the goal posts 58 yards away.

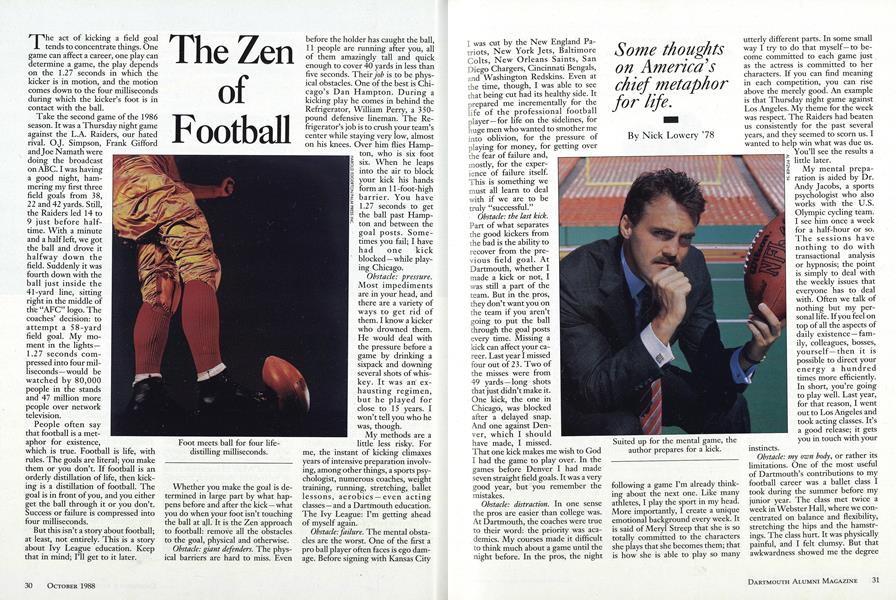

Foot meets ball for four life-distilling milliseconds.

Suited up for the mental game, the author prepares for a kick.

Lowery's Dartmouth career took off after he learned ballet.

"My courses made itdifficult to think much abouta game until the nightbefore."

"The more you can put down on paper,the more you can absolutely understand thekick, the better the kick.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

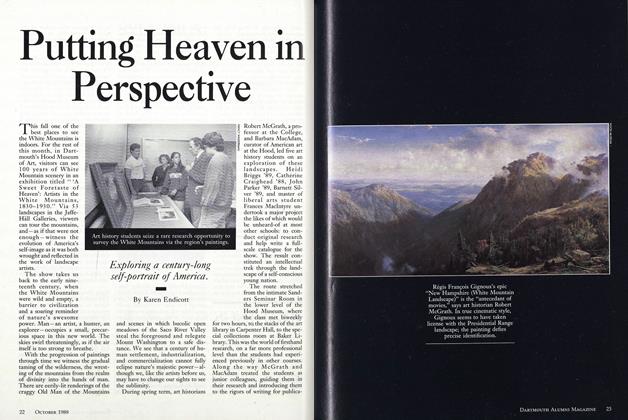

Cover StoryPutting Heaven in Perspective

October 1988 By Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureScions Of The Times

October 1988 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

FeatureChecking into the Inn and Out of an Era

October 1988 By John Townsley -

Feature

FeatureIs the Indian Symbol a Right or an Opportunity?

October 1988 By George B. Harris III '50 -

Article

ArticleFunded Research Rises

October 1988 -

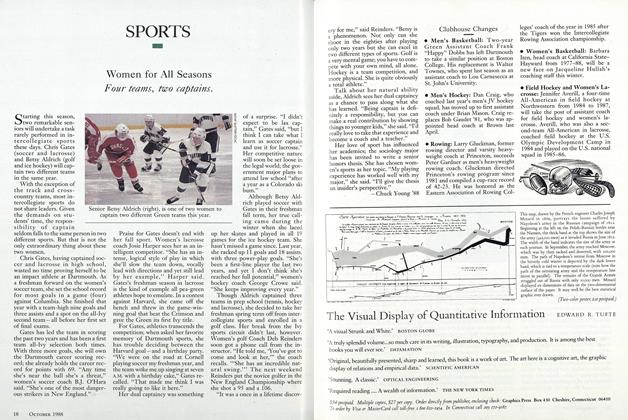

Sports

SportsWomen for All Seasons

October 1988

Features

-

Feature

FeatureANNELISE ORLECK

Sept/Oct 2010 -

Cover Story

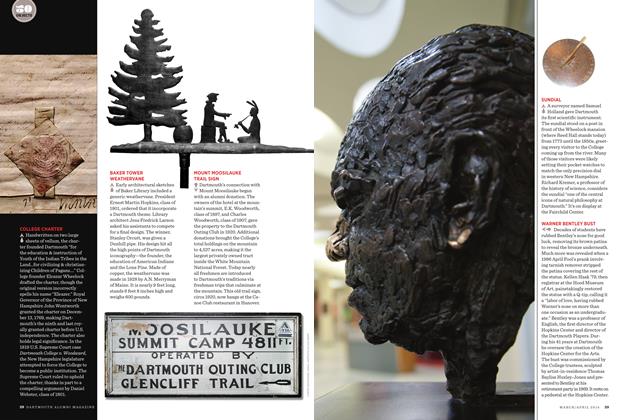

Cover StorySUNDIAL

MARCH | APRIL 2014 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryIn Two Worlds

May 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryAs We See It

JUNE 1999 By Julian Okwu '87 -

Feature

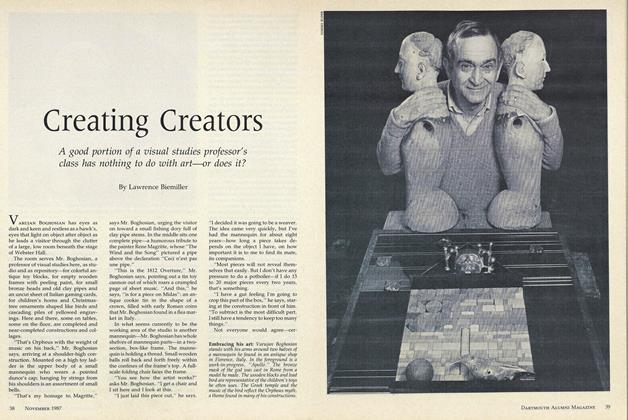

FeatureCreating Creators

NOVEMBER • 1987 By Lawrence Biemiller -

Feature

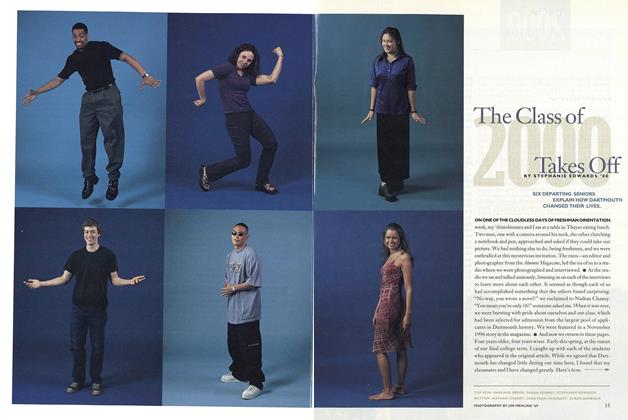

FeatureThe Class of 2000 Takes Off

JUNE 2000 By STEPHANIE EDWARDS ’00