Exploring a century-longself-portrait of America.

This fall one of the best places to see the White Mountains is indoors. For the rest of this month, in Dartmouth's Hood Museum of Art, visitors can see 100 years of White Mountain scenery in an exhibition titled " 'A Sweet Foretaste of Heaven': Artists in the White Mountains, 1830-1930." Via 53 landscapes in the JaffeHall Galleries, viewers can tour the mountains, and - as if that were not enough - witness the evolution of America's self-image as it was both wrought and reflected in the work of landscape artists.

The show takes us back to the early nineteenth century, when the White Mountains were wild and empty, a barrier to civilization and a soaring reminder of nature's awesome power. Man—an artist, a hunter, an explorer—occupies a small, precarious space in this new world. The skies swirl threateningly, as if the air itself is too strong to breathe.

With the progression of paintings through time we witness the gradual taming of the wilderness, the wresting of the mountains from the realm of divinity into the hands of man. There are eerily-lit renderings of the craggy Old Man of the Mountains and scenes in which bucolic open meadows of the Saco River Valley steal the foreground and relegate Mount Washington to a safe distance. We see that a century of human settlement, industrialization, and commercialization cannot fully eclipse nature's majestic power—although we, like the artists before us, may have to change our sights to see the sublimity.

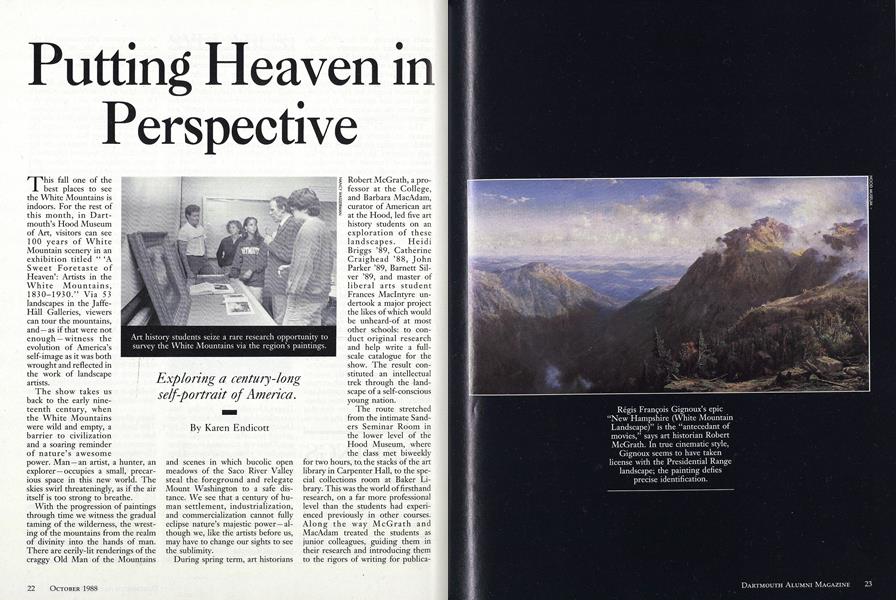

During spring term, art historians Robert McGrath, a professor at the College, and Barbara MacAdam, curator of American art at the Hood, led five art history students on an exploration of these landscapes. Heidi Briggs '89, Catherine Craighead '88, John Parker '89, Barnett Silver '89, and master of liberal arts student Frances Maclntyre undertook a major project the likes of which would be unheard-of at most other schools: to conduct original research and help write a fullscale catalogue for the show. The result constituted an intellectual trek through the landscape of a self-conscious young nation.

The route stretched from the intimate Sanders Seminar Room in the lower level of the Hood Museum, where the class met biweekly for two hours, to, the stacks of the art library in Carpenter Hall, to the special collections room at Baker Library. This was the world of firsthand research, on a far more professional level than the students had experienced previously in other courses. Along the way McGrath and MacAdam treated the students as junior colleagues, guiding them in their research and introducing them to the rigors of writing for publication. "We really expected them to make a contribution to the exhibition," McGrath says. "By the end of the term, some of the students knew as much as or more about some things than we did."

According to McGrath, in most institutions only graduate students in art history have the chance to write exhibition catalogues, and even then the work does not always involve original research. The White Mountains exhibition marks the fourth time that the professor has involved Dartmouth undergraduates in the preparation of catalogues. An especially high proportion of original research was required in this class, however, because many of the paintings had never before been studied by art historians.

"It's exciting for students to have the opportunity to do primary research with unpublished works of art; too much of education tends to be passive and receptive," he contends. "This engages them in a way they don't usually get to do." Moreover, the opportunity to work with actual paintings was itself a rare experience, according to Catherine Craighead, holder of the art history department's Jaffe Prize for Excellence and one of the finest art history students McGrath says he has ever taught. "Most other art history courses use slides," Craighead explains. "This was an unusual, hands-on experience."

The exhibition features works selected by McGrath and MacAdam to show the range of artists and styles associated with the White Mountains from1830to1930.Mostofthe paintings are part of the Hudson River School genre of art that helped forge a national identity through its depictions of the land, according to McGrath. "The exhibition shows the locations other than the Catskills and Adirondacks that the Hudson River School artists painted."

About half of the exhibit's landscapes belong to the Hood, and the other half are on loan from private collections. Many are the works of little-known "minor masters," to use McGrath's term, although the show also includes some of the betterknown names in White Mountain art: Thomas Cole, Thomas Doughty, and Benjamin Champney, for example. Still, there was plenty of documentation for the students to do. Each was responsible for producing exhibition catalogue entries for ten works, while McGrath and MacAdam contributed major essays on the paintings' historical and cultural background and the history of America's first art colony, at North Conway, New Hampshire.

The significance of their work extends beyond the show itself, according to Hood Museum director Jacquelynn Baas, who asserts that art historians increasingly recognize museum catalogues as serious academic publications. In fact, she says, "the best art scholarship in recent years has been in catalogues."

McGrath agrees that this is happening in the field of American art, which is "still in its infancy—though we're maturing at last," as he says. "An exhibition can literally help redefine the configuration of a period. Bringing together works of art that we have never seen together before allows new perspectives to be explored and new scholarship to be done," the professor explains.

The current exhibition owes more than a visual debt to the White Mountains region. Eighty-six scenes, mostly nineteenth-century landscapes, were donated to the Hood recently by Robert Goldberg, a North Conway antique dealer, entrepreneur, and art collector whose primary Dartmouth connection is his friendship with McGrath. Goldberg initially offered the collection to his hometown, with the proviso that the town create a museum to house the art within a year of the gift. When North Conway was unable to comply, Goldberg presented the collection to the Hood. Dartmouth already owned 30 White Mountain paintings, most of which had been acquired by former curator Jerry Lathrop during the 1930s and 1940s. According to McGrath and MacAdam, Goldberg's gift instantly transformed Dartmouth into a center for White Mountain art.

The paintings complement a vast collection of White Mountain material in Baker library that comprises more than 2,600 books, manuscripts, and broadsides — ranging from diaries to hotel ledgers to scientific measurements—and more than 3,500 photographs and stereographs. "It is the premier White Mountains archive," claims special collections librarian and curator of manuscripts Philip Cronenwett.

Still, McGrath had some regrets that the Goldberg collection was leaving North Conway. "I felt that the proper home for this art was somewhere in the White Mountains," he says. "Dartmouth now has a trust to uphold." When Baas suggested showing the new art in a fall exhibition, McGrath leapt at the chance "to justify having the collection here," as he puts it. "And by involving students in the exhibition we were fulfilling a primary charge of the Hood to serve the education of students."

McGrath, who is an expert on the art of the White Mountains, teamed up with curator MacAdam, a specialist in American art, to organize the exhibit. Timing imposed some constraints on student participation in the project. "It was difficult to involve the students in the beginning and end of the work because of the short term," MacAdam says, "so we decided to have the students concentrate on research and writing." MacAdam and McGrath attended to the numerous details of the project's initial and final stages, determining the exhibition's scope, arranging for loans of paintings from private collections, making final revisions to the catalogue, and planning the installation and opening of the show.

Before they could expect their students to write professional-level catalogue entries, the two historians had to acquaint the class with the requisite research and aesthetic skills. They led the students on a tour of the Hood's White Mountain art, introduced them to the research materials available in Baker Library's special collections, and then turned to a discussion of catalogue entries. They assessed the topics that are essential to good catalogue entries: biographical information, artistic influences on painters (Had they been to Europe? With whom did they study?), styles of the paintings, and the historical, social and artistic contexts in which the art should be placed. McGrath holds that "a good catalogue entry clearly and succinctly describes what's unique about a work of art, both as an aesthetic object and as a communicator of ideas. A good catalogue entry will insightfully describe those qualities. A great catalogue entry will put the art in a context, in a relation to other works, that will give new insights never seen before." Says graduate student Frances Maclntyre of the perspectives and skills McGrath and MacAdam were imparting: "We learned how to look at art."

Clearly, that aesthetic "how" goes far beyond merely knowing what one likes. "Art is an acquired taste," McGrath says. He adds, smiling, "You can't go directly from Coke to a martini and expect to really appreciate the martini. There are a lot of drinks, a lot of tastes, in between. There are a lot of levels of looking at art, but it's the informed viewer who really understands what the artist is doing."

Drawing from the essays the two art historians had prepared for the exhibition catalogue, McGrath grounded his class in the historical, social, and artistic contexts of the White Mountains art, and MacAdam traced the history of the North Conway art colony. Both feel that the genealogy of styles that span the century of artistic enterprise in the White Mountains is a record of the way America was changing—and, conversely, the changing way that America was looking at itself. As McGrath writes in the exhibition catalogue, "The task of formulating a definition of the American self fell to artists and writers from the founding of the country."

Artistic activity began in the White Mountains when Thomas Cole, an artist of the Hudson River School, left the increasingly populated Catskills in 1827 to explore the New Hampshire wilderness. His earliest renderings of the White Mountains conveyed the terror and might of the wilderness, awesomely sublime in its raw and dangerous beauty. He painted scenes of natural disasters, such as the site where the Willey pioneer family perished in a sudden mudslide. Cole filled his canvasses with subjects and images—"blasted stumps, errant boulders, and jagged forms," in McGrath's words —intended to invest the wilderness with mythical meaning.

The American wilderness, much emptier and less tame than Europe, became a defining symbol of the emerging nation. This national iconography was imbued with the stamp of divine authority: Americans found their new nation to be closer to the way the world was at creation than was Europe, which had been despoiled by centuries of human habitation. Cole took up this belief and imposed symbols of divinity onto his White Mountain landscapes in the form of swirling skies, shafts of light, and intertwining living and dead tree branches. Even "light itself is evidence of the spiritual" in these paintings, MacAdam explains.

Influenced by Cole's example, many artists from New York and Boston turned to the wilds of nearby New Hampshire. By the middle of the century, artists Benjamin Champney and John Frederick Kensett had taken up summer residence at a North Conway inn. The proprietor, Samuel Thompson, had opened his home for years to passing artists and had been instrumental in getting a stage coach line to supplement the mail teams' thrice-weekly service to North Conway. Kensett painted a landscape titled "The White Mountains—Mt. Washington" that was reproduced by the thousands and inspired many more artists to come. From this beginning, America's first art colony took shape.

Artists were not the only ones to flock to the area. As the century wore on, people tamed the wilderness through farming and settlement, befriended it through recreational outings, and eventually mastered—some would say defiled—it through industrialization. Paintings of the era came to reflect the changes. Pastoral scenes increasingly pushed the mountains to the background; imported European styles, such as Impressionism, became the focus of art, de-emphasizing the uniqueness of the American landscape; even tourist accommodations, and tourists themselves, supplanted the landscape as the artists' chief interest. By the turn of the century, tourism, industry and logging had caused most painters to turn away from the White Mountains altogether. Paradise had been compromised. McGrath quotes Oliver Wendell Holmes's observation that "the mountains and cataracts which were to have made poets and painters have been mined and dammed."

Besides, the American character itself was no longer tied to the wilderness; the national energy now flowed from its rapidly urbanizing soul. "During the first decade of the twentieth century," McGrath says, "artists of the newly imported modernist persuasion tended to focus on the city, the cafe, and industry in defining their brave new world." Only a few artists continued to work in the White Mountains into the 1930s, experimenting with modern styles, but the heyday was long past. The Dartmouth seminar bounced its research off this cultural and historical background. At each class the students presented their initial findings, holding up both the art and their research to the scrutiny of their classmates and to McGrath's professorial and MacAdam's curatorial eye. Everyone was encouraged to point out revealing details in the art or direct a researcher to a particularly useful reference book. McGrath and MacAdam collegially welcomed all perspectives. As MacAdam says, "No two pairs of eyes are going to see exactly the same thing."

.The classroom presentations, while demanding, were just the prelude to the real work of writing—and rewriting and rewriting—the catalogue entries, all directed by the two teachers.

MacAdam maintains that "it is a valuable experience for students to have their work edited before they leave college." In the end the students agreed, although there were maddening moments along the way. "It was hard to spend senior spring only working, never seeing light at the end of the tunnel," admits Craighead. The students say that what saved them from feeling enslaved by their professor/editors was the same sense of collegiality that pervaded the classroom sessions. "We were definitely working with them, not for them," stresses John Parker.

Some of the differences McGrath and MacAdam brought to the classroom and to the editing process reflect their individual personalities and experiences as much as their professional specialties. McGrath, an avid skier and hiker who spends as much time in the White Mountains as he can, is an expert on the area's geography; he can tell at a glance how much license an artist has taken with the landscape. For example, McGrath points out that Thomas Doughty distorted the scenery in his painting, "Rowing on a Mountain Lake." "You can't see Cannon Mountain from Echo Lake like that," says the professor. McGrath sees little difference between his vocational and recreational interests. "My xerience of perceiving nature is so intertwined with my perception of art that I hardly know anymore where art begins and reality leaves off," he muses. He had hoped to give his seminar students a firsthand taste of this experience by taking them into the White Mountains during the term for a "classroom in the clouds" something for which he is famous at Dartmouth — but the enormity of the workload chained them to their desks. Still, even within the seminar room he clearly managed to convey the perceptual magic that links imagery and actuality. MacIntyre recalls that when she pulled over at a scenic viewpoint near North Conway, she stepped out of her car, turned around, and her mouth fell open. "There was my painting—Delbert Dana Coombs's 'Mount Washington from the Saco River'— right down to the fences!"

MacAdam, for her part, contributed technical as well as historic expertise to the project. McGrath considers MacAdam's research on North .Conway's artist colony to be a "major contribution to art history." Co-teaching the seminar was her first experience with Dartmouth students aside from the museum's student interns she has worked with since she came to the College in 1983.

MacAdam spends time hiking and skiing in the White Mountains, but she discounts herself as a serious sportswoman ("I'm mildly athletic," she laughs) or an authority on geographical details. "My introduction to the White Mountains was as much through the art as through trips."

In class MacAdam concentrated on teaching students the tricks of the curatorial trade. She drew attention to details such as brushstrokes and pigments, and how the medium on which the paintings were executed - masonite versus canvas, for example—influenced the final effects. She taught the students how to look for evidence of restoration work by scrutinizing paintings under ultraviolet light. "We need to know whether it was done well or seriously compromises the work," she explains.

The teachers' dual approach exposed their students to the world of professional academic collaboration. But there was a third participant, of a sort: the Hood Museum, which was originally designed as an educational focal point for the College. According to "A Statement of Purpose for the Hood Museum of Art," the Hood serves four clients: the academic community at large, students and faculty interested in the visual arts and material culture, the people of northern New England, and the scholarly world at large. The White Mountains project — from its inception to its growth in the classroom to its appearance on the gallery walls and in the pages of the catalogue — is geared to all those audiences.

In addition, various College divisions are keying into the exhibition. Baker Library is highlighting its collection of White Mountains material in its corridor showcases, Environmental Studies Professor James Hornig is lecturing in the Loew Auditorium about the effects of acid rain in the White Mountains, and the office of Alumni Continuing Education and the Dartmouth Club of the Upper Valley are cosponsoring a day-long seminar featuring Geology Professor John Lyons on the formation

of the White Mountains and Professor McGrath on changing perceptions of the mountains. In addition, the Hood has arranged for a speaker from outside the College, Richard Ober of the Society for the Preservation of New Hampshire Forests, to lecture at the Loew Auditorium on "Preserving the Land."

The seminar participants themselves were planning to be on hand for the exhibition's opening. Shortly after she graduated, Catherine Craighead previewed the thrill of seeing the finished product. "I was taking a cousin on a tour of Dartmouth," she recalls. "We went to the Hood and looked for one of the paintings I had researched, and there it was with caption information I had written! "It was very exciting. You feel like you're really contributing."

Art history students seize a rare research opportunity to survey the White Mountains via the region's paintings.

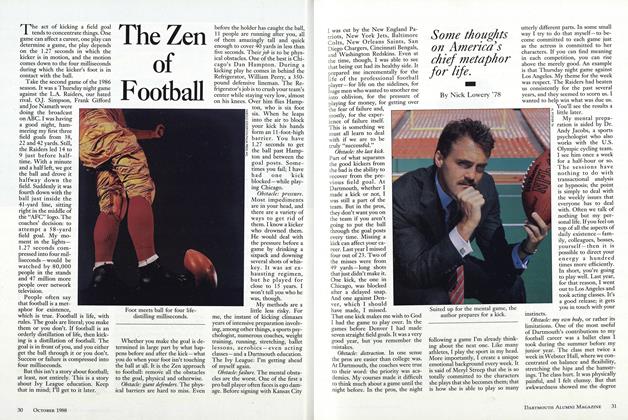

Regis Francois Gignoux's epic "New Hampshire (White Mountain Landscape)" is the "antecedant of movies," says art historian Robert McGrath. In true cinematic style, Gignoux seems to have taken license with the Presidential Range landscape; the painting defies precise identification.

Curator Barbara MacAdam, an American art specialist, teamed up with Robert McGrath, who is an expert on the art of the White Mountains, to organize the exhibition. They rode editorial herd over their seminar students to produce a professional-quality museum catalogue.

American artist Sanford R. Gifford admired the work of Thomas Cole, the first Hudson River School painter to do the White Mountains. Gifford in turn inspired other artists in the genre to employ the formula he brought to this circa-1854 painting, "Mount Washington from the Saco." A serene pastoral foreground sprawls before a classic mountain landscape.

The setting that once inspired Champney still exists beyond North Conway's outlet stores.

Marguerite Zorach's 1915 "White Mountain Landscape" reflects the modernism that helped turn artists to new American themes: cities, cafes and the West.

Karen Endicott is the magazine's faculty editor. The exhibition's catalogue is available for $17.95 at the Hood Museum or the University Press of New England, 17½ Lebanon Street, Hanover, NH 03755.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureThe Zen of Football

October 1988 By Nick Lowery '78 -

Feature

FeatureScions Of The Times

October 1988 By Fritz Hier '44 -

Feature

FeatureChecking into the Inn and Out of an Era

October 1988 By John Townsley -

Feature

FeatureIs the Indian Symbol a Right or an Opportunity?

October 1988 By George B. Harris III '50 -

Article

ArticleFunded Research Rises

October 1988 -

Sports

SportsWomen for All Seasons

October 1988

Karen Endicott

-

Article

ArticleEXPLORING AN ANCIENT FACTORY TOWN

FEBRUARY 1989 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleProfessor Katharine Gingrass-Conley:

May 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMaking the Walls Talk

June 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticlePatient Talk

September 1993 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleMemory and Catastrophe

June 1995 By Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleCONFRONTING CHEMOPHOBIA

December 1991 By Professor Gordon W. Gribble, Karen Endicott

Features

-

Feature

FeatureHONORARY DEGREE CITATIONS

JULY 1963 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDartmouth’s Unknown History

JANUARY 2000 -

Feature

FeatureReligion and the Biological Revolution

JANUARY 1973 By CHARLES H. STINSON, ASSISTANT PROFESSOR OF RELIGION -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

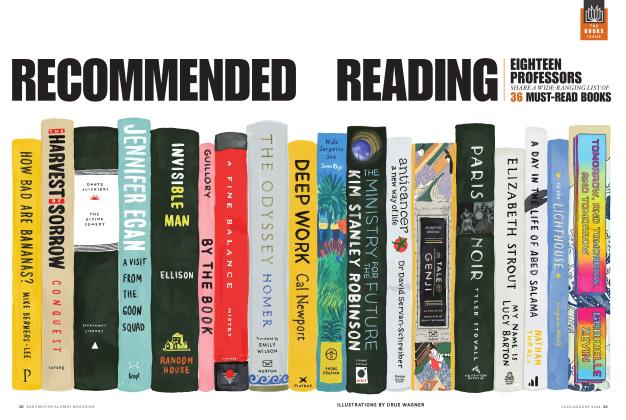

Features

FeaturesRecommended Reading

JULY | AUGUST 2024 By Joanna Jou '26, Caroline Mahony '25, Heya Shah '26, 1 more ... -

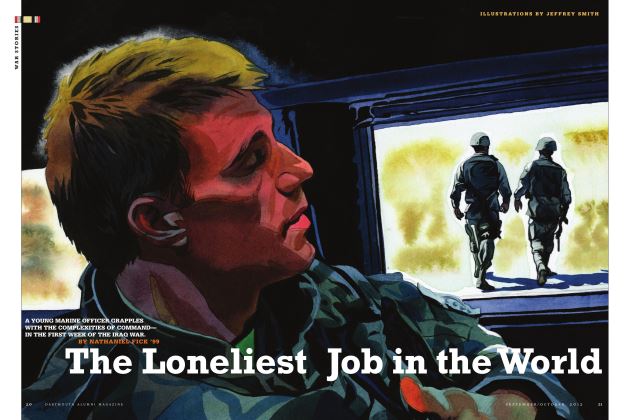

Feature

FeatureThe Loneliest Job in the World

Sep - Oct By NATHANIEL FICK ’99