David McLaughlin had a take charge style. He was a detail man who met often with low-level College administrators, and he occasionally bruised academic egos by making unilateral decisions.

James O. Freedman's style is altogether different. He is a delegator: only deans and vice presidents report to him directly. Although he regularly attends fundraising meetings and listens to reports on the College's physical plant, he obviously perks up when the talk turns to academic programs and curricula.

But if there is a single trait that sets Freedman apart as a president, it is his way of seeking change through public "conversation." McLaughlin gave orders; Freedman gives speeches.

He has created a tapestry of thought by weaving through his addresses memorable phrases that get repeated on campus: "commonwealth of liberal learning," "the quiet, measured force of our reason," "a hospitable environment for students who march to the beat of a different drummer," "creative loners and daring dreamers," "commit yourself to defining a private self," "move to the measure of the scholar's thought."

The sum total of these phrases creates a Dartmouth fundamentally different, in some ways, from the College that exists today: an intellectual enterprise where the serious, focused student is favored over the well-rounded one, where the artist stands at least as high as the athlete, where the loner feels welcome among Dartmouth's traditional joiners.

Freedman's specific proposals are few:

• A recruitment effort that brings in more women, more minority students, more foreign students, and more intellectuals and artists.

• A renewed emphasis on faculty recruiting.

• A stronger international curriculum that stresses the Pacific Rim.

In focusing on these few issues, Freedman has chosen to ignore publicly the controversies that occupied much of Dartmouth conversation in the past—the Indian, the alma mater, fraternities, athletics. When asked about fraternities or athletics he states simply that he is for them. When asked about the Indian or the alma mater he makes it clear that he finds these issues less significant than academic ones.

This circumspect, speechifying style is not universally admired. "While President Freedman might have the best speeches since Dickey/' asserts the Dartmouth Review, "he hasn't done anything substantial." But that criticism precisely misses the point. To Freedman, chief executive of a large, inertial academic institution, speech is action. "By voicing my goals in public, I hope to create a climate that allows sympathizers to bubble to the surface," he told the Alumni Magazine recently.

Freedman's speeches also bring some detractors to the surface. His most controversial theme is his call for more intellectually inclined "creative loners." Ray Sozzi, president of the sophomore class, wrote to the Daily Dartmouth: "It would be a tragedy if Dartmouth were to increase intellectualism on campus at the expense of the spirit, comraderie [sic] and social warmth that make this college so special."

Other students feel a bit insulted by the implied shortage of Dartmouth intellectuals. "In assuming that a different type of person should be accepted to the College," stated the student newspaper Common Sense, "it is presupposed that those with the intellectual capabilities the faculty so deeply desires are not currently enrolled at Dartmouth."

Freedman replies that his initiative merely plays to Dartmouth's "traditional strength" of "highly gifted students" taught by "greatly dedicated teachers." "In the years ahead," he adds, "I hope that we will renew our commitment to this deeply traditional mission."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

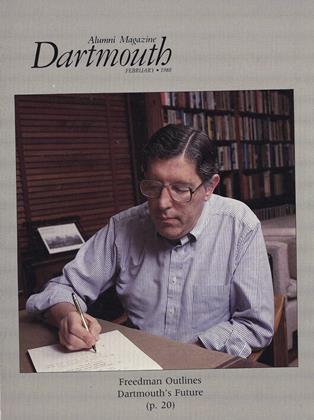

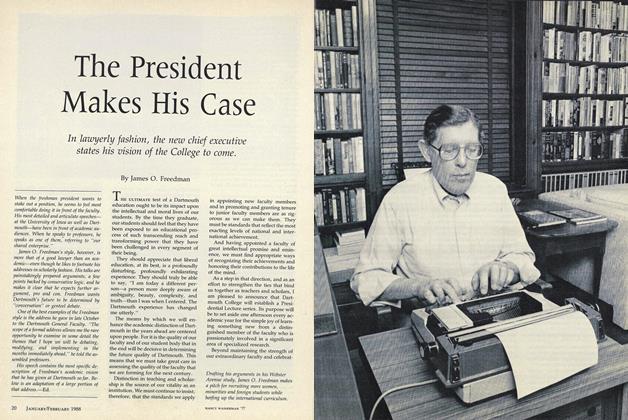

Cover StoryThe President Makes His Case

February 1988 By James O. Freedman -

Feature

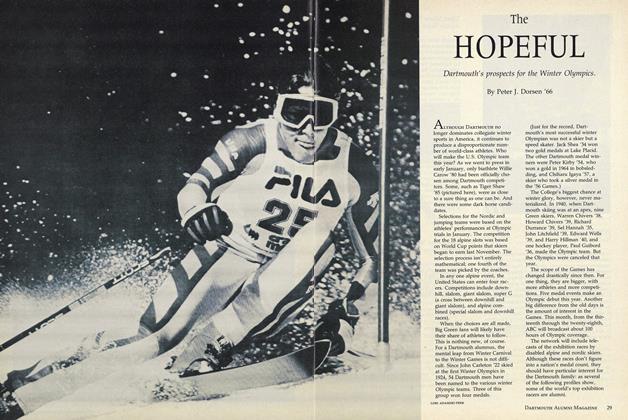

FeatureTHE HOPEFUL

February 1988 By Peter J. Dorsen '66 -

Feature

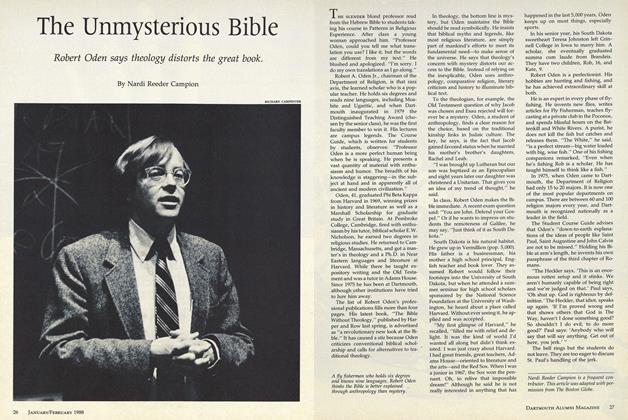

FeatureThe Unmysterious Bible

February 1988 By Nardi Reeder Campion -

Sports

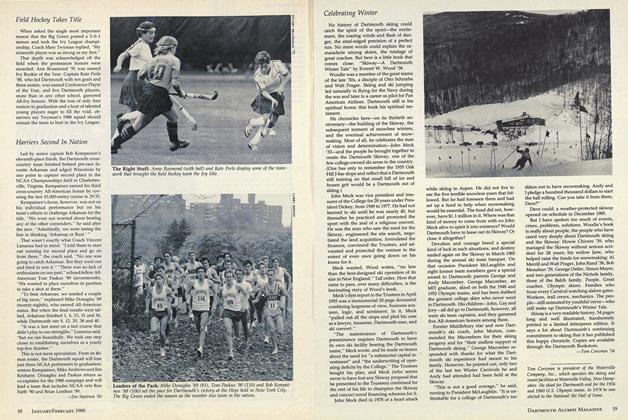

SportsCelebrating Winter

February 1988 By Tom Corcoran '54 -

Article

ArticleDartmouth Authors

February 1988 -

Article

ArticleFour Alumni Authors from the '40s to the '80s

February 1988

Article

-

Article

ArticleChapter Three: The Kid Gets a (New) Life

DECEMBER 1998 By "Mom" -

Article

ArticleTHE SESQUI-CENTENNIAL

December, 1919 By George Levi Kibbee -

Article

ArticleSt. Louis

MARCH 1972 By HARVEY M. TETTLEBAUM '54 -

Article

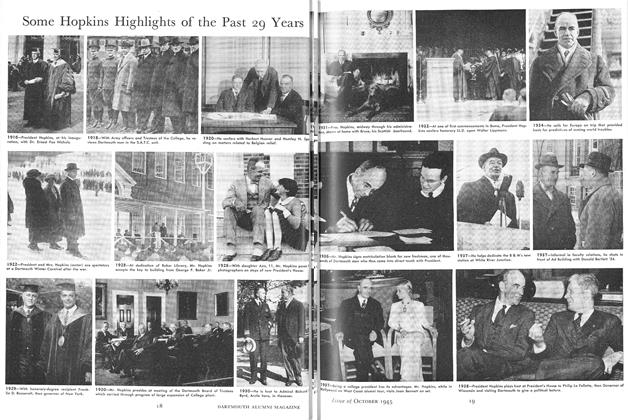

ArticleTo Men of Dartmouth

October 1945 By John Sloan Dickey. -

Article

ArticleFRATERNITIES UNDER FIRE

January 1935 By Milburn McCarty IV '35 -

Article

ArticleTHE MEANING OF TOLERANCE

May 1948 By W. K. JORDAN