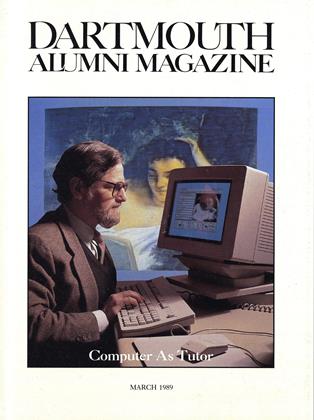

After years of hype, the personal computer is becoming more than an expensive typewriter.

Biochemistry will never be easy, but students taking classes from Professor Robert Gross don't have to spend hours reviewing key topics in a textbook. Instead, they can flip on their Macintosh computer and run a program called Techniques in Molecular Genetics. Written by Gross to augment his lectures and labs, Techniques efficiently packages material found in a traditional printed text. It also transforms the computer into a tutor, drill instructor, study companion and lab assistant.

Without leaving their dorm-room Macs, Gross's students can study column chromatography, DNA sequencing, assays chromatography, gel electrophoresis, nucleic acid hybridizations, DNA cloning and centrifugation. Text and graphs communicate the hard facts. Descriptions of laboratory techniques are augmented by computer-generated animation. Question-and-answer sessions help students with their allnighters. Should an unknown word crop up in the reading, no problema simple click of the mouse, and a definition appears on the screen.

This sort of student-computer interaction was heralded at the onset of the computer age, and nearly two decades of hoopla followed. In reality, however, computers generally made lousy tutors. "Computing got a bad name in instruction because of the limitations of computer-assisted learning," recalls David Bantz, Dartmouth's director of humanities computing. "You answered some questions, and if you got them wrong, you'd go back a step; if you got them right you'd get to do the next step."

With growing number,s of computer-literate faculty members and the invention of HyperCard, a new kind of computer program developed by Apple, software is not nearly so clunk. "HyperCard is the first program I've seen that functions in a way similar to the human mind," maintains Assistant Professor Harold Lyon of the Medical School. "It has the ability to let the user make all kinds of leaps and jumps and connect things by association." Lyon, an education expert, is coordinator of a faculty team under contract with Apple to teach other academics how to use HyperCard. The team is developing programs that purportedly don't just test but actually teach.

Physics Professor Bruce Pipes had teaching in mind when he used HyperCard to design Quantum Mechanical Weirdness. The concepts Pipes sought to present are difficult to describe and even harder to comprehend. "Understanding the principles of quantum mechanics," Pipes explains, "requires that the student let go of some preconceived notions, such as the belief in an objective reality that is independent of the observer, or the idea that something cannot be simultaneously true and false." Students running QM Weirdness conduct "thought experiments" consistent with the principles of quantum mechanics the students' choice of variables affects the results. A particle detector in one experiment shows an electron behaving as a particle; choice of a wave detector in the same experiment reveals the electron as a wave. These two types of behavior are mutually exclusive in classical physics, but not in the bizarre realm of quantum mechanics.

Dartmouth's crop of courseware (computer lingo for educational programs) is not confined to science. Building on a concept pioneered by two Mt. Holyoke professors, Dartmouth programmers, students and faculty members have teamed up to write Hanzi Assistant, a Chinese language drill. The program makes the Macintosh computer speak aloud in Chinese, pronouncing the character displayed on the screen in a clear, digitally recorded but not unfriendly voice. Hanzi Assistant also shows the correct order of a character's brush strokes and can run drills in translation and pinyin the Romanized version of a word or character.

Hanzi Assistant is easily adaptable to other languages, such as Japanese or Arabic, according to Otmar Foelsche, manager of the College's Language Resource Center. Moreover, he says, faculty can enlist campus computer experts and low-paid student programmers to develop other HyperCard applications for less than $2,000 a fraction of the cost of conventional specialized programs.

Part of the hype behind HyperCard, in fact, is that it is easy enough to turn almost everyone into a programmer. As is often the case in the computer industry, however, the promise has fallen short. "I haven't seen a lot of professors using it themselves," says Ashley Chadowitz '89, who worked on two HyperCard applications. Instead, he observes, "a lot of students are being hired to write things with it for professors."

As a HyperCard test site, Dartmouth got a jump on other academic institutions in developing applications for the classroom. Dartmouth faculty and programmers revealed HyperCard's potential by writing a series of educational programs. As a result, Dartmouth software is often demonstrated at workshops in this country and abroad. (Last October a Dartmouth delegation which included Bantz and Foelsche visited West Germany to demonstrate HyperCard courseware.) Among the Dartmouth-developed programs that have "toured" are:

• Heavenly Mac a computerized textbook that uses working models of celestial motion to illustrate the history of astronomy from ancient times to Newton.

• Mnemosyne a guide that allows users to find their way through a collection of paintings at the National Gallery of Art that have been reproduced in color on video disk.

• Interactive Medical Record employs animation, sound, and videodisk images to illustrate medical case studies. Med students can hear an artificial patient's pulse, see the area operated on and review test samples.

• Textwindow Functions a German and English dictionary. A student reads text" on the screen and clicks on any unknown word. The computer instantly provides a definition. Officials say Textwindow will soon be expanded to include a French and Spanish vocabulary.

New applications are burgeoning. Med School Professors Lyon and J. Robert Beck '75 are developing two "expert systems," computer programs that embody the specialized knowledge of professionals. For example, programs will show medical students how to do chest-pain and anemia workups.

Despite constant upgrading, these HyperCard applications do not seem to come close to meeting the technology's true potential. Some critics say the software has not even reached the point of real utility. Few of the applications have actually been used by many undergraduates, half of whom do not even own computers powerful enough to run HyperCard.

In fields with a welter of technical material, however, supporters seem to outnumber the critics. Biology Professor Gross says he used to spend two or three days lecturing on one aspect of the interaction of viruses and bacterial cells; now, with the aid of his HyperCard program, he covers the same material in less than half an hour. Students learn the material more quickly, says Gross, and test results show they have a better grasp of the material than in the past.

Another advantage is the speed with which technical material can be updated. Gross's own field of molecular genetics is changing so rapidly that "if you put out volumes of information detailing the techniques, six months or a year later they'll be outdated," he says. HyperCard allows the professor to update material in a fraction of the time it takes for a book publisher to revise, print and distribute revised texts.

These advantages still don't prove that computers can make for more effective teaching than the conventional mix of textbooks and seminars. The Medical School team of Lyon and Beck say they are conducting comparison tests to find out. Harold Lyon already has a hypothesis. "The computer doesn't replace the professor," he says confidently. "It enables the professor to be a mentor, to nourish and stimulate students' critical thinking while providing a degree of variety beyond what they can get from a lecture."

From computers in their dorms, students can explore Baker Library, study genetics or practice Chinese.

Professor Gross's program augments lab work

Otmar Foelsche sees computers becoming more important in the area of language instruction.

Hanzi Assistant demonstrates the brushstroke order for the Chinese character that means "middle."

Experts believe computers will make students better thinkers.

Freelance writer Paul Susca lives in Rindge, New Hampshire.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom Dartmouth Comes the World's First Love Story

March 1989 By David Birney '61 -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

March 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWhy I Traded Basketball for Biology

March 1989 By Liz Walter '89 -

Article

ArticleTHE NATURE OF REALITY

March 1989 By Bruce Pipes, Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOROZCO'S LEGACY

March 1989 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

March 1989

Features

-

Feature

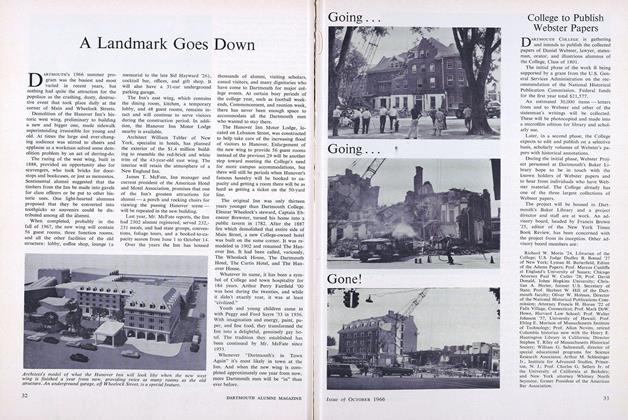

FeatureA Landmark Goes Down

OCTOBER 1966 -

Cover Story

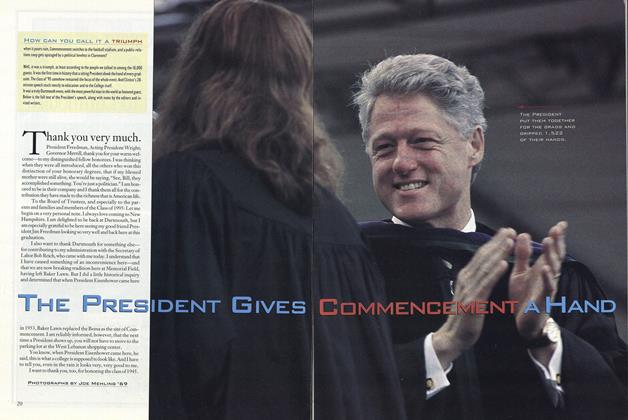

Cover StoryThe President Gives Commencement a Hand

September 1995 -

Feature

FeatureA Dartmouth History Lesson for Freshmen

December 1957 By FRANCIS LANE CHILDS '06 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

FEBRUARY 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureHow Much Government?

March 1954 By LAURENCE I. RADWAY