VOX

The ways in which an actor prepares for a performance are often unknown, even to him. Sometimes the preparation becomes clear only after the curtain goes down. An example of this process will appear in April, when a stage adaptation of Mark Twain's "The Diaries of Adam and Eve" will air as part of the PBS series, American Playhouse. The work had its origins at Dartmouth, both literally and figuratively, though I didn't know it at the time. And what began as a charming chamber piece for two actors my wife, Meredith, and I turned out to have a resonance and depth far beyond what I had expected.

I bought Twain's Adam and Eve "Diaries" in a bookstore years ago. Written at different times, they were published as separate pieces in a single volume. Twain, certainly America's greatest humorist and, perhaps, its greatest writer, had fascinated me since I'd encountered him at Dartmouth in Henry Terry's course in American literature. I'd read Twain before, of course, but Terry's reading of Twain, the rough-edged, robust humor, the brilliant, scathing use of irony, the passionate moral vision, was a revelation, one that I carried with me long after that class.

Some years later, I found myself reading The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn aloud to my children, all of us moved to share laughter and tears as we re-created that extraordinary river journey. Much of Twain, especially Huckleberry Finn, is wonderful to read aloud; even better, in some ways, than Dickens the full meaning revealed in the breath and passion of the telling. So in reading the "Diaries," I was alert to their dramatic possibilities.

Twain wrote "Extracts from Adam's Diary" during the early 1890s, amid his own failing fortunes and the increasing difficulty of his wife's ill health. The story was originally entitled "The First Authentic Mention of Niagara Falls." It is a kind of extended joke in the tradition of the music hall or vaudeville: Adam, the original male, is unable to understand this "new creature with the long hair." Pursued by Eve, exasperated by her need (and ability) to name everything in the Garden, Adam flees just before the Fall. Eventually, living with her outside the Garden, he grows accustomed to her company, realizing he would be "lonesome and depressed without her." Cain and Abel are born, and the amazed and bewildered Adam attempts to conduct a series of experiments designed to define and classify these new creatures he suspects them of being everything from fish to bear.

"The Diary of Eve" was written nearly a decade and a half later. Twain had lost three children and his fortune and, most tragically, his beloved Livy had died. This second piece responds to the first one, as if Twain were extending it, except that Eve's diary has a completely different feel, a lyrical, elegiac quality. It is his attempt, I think, to recapture his enormous love for his wife, to re-create that love in the midst of his loss. In effect, Twain mythologized his wife as the first female, the first wife in whom all others would be repeated.

It seemed that possibly the two pieces might be edited and adapted for the stage, interwoven to re-create that first meeting of man and woman in the primal garden in dramatic terms. But how and where to test this idea?

My opportunity to interpret Twain for a larger audience came in 1986. I'd spent time at the College on several occasions as a visiting professor in 1980, on tour with "Talley's Folley" in '81, and, later, in a short stint as a Fellow of my class. Each of these experiences had been fruitful.

Dartmouth for me has been a place for self-renewal. The choice of the College as a place to try "Adam and Eve" seemed inevitable. The Hopkins Center was ideal, both as a facility for performance and as a sounding board, a gathering place for some of the best audiences in the country. Hanover audiences are bright, informed, sophisticated on many levels, yet still retain an openness, a freshness that has long since disappeared in the larger theatre cities. I called Shelton Stanfill, then director of the Hopkins Center, and asked if there was space available at Dartmouth to rehearse "a work in progress" during the summer. The center extended its hospitality.

On several occasions, I had fooled with the idea of "Adam and Eve" as a piece for two voices to be read (once as a benefit for Dartmouth), so I had a crudely edited version on hand when I arrived in Hanover. The next two weeks were spent in a process of trial and error, editing, reorganizing, rehearsing in the afternoon, reediting the two pieces at night, trying to leave out as little as possible.

In spite of my admiration for the audiences of the Hanover Plain, my fear was that the "Diaries" might not play well that a university audience might be supportive but a little too sophisticated for Twain's roughedged "traditional" humor. On the page, the humor seems obvious, perhaps a little sentimental. But I had misread the piece. In the course of live performance, traditional jokes in the ancient convention of the "battle of the sexes" are transformed, altering not only our perception of Adam and Eve but also their perception of each other.

The audience helped us understand this. The Fall isn't as profoundly moving on the page as it is onstage. In performance we found a whole world existing under the words-in cracks and crevices within the piece. And the college audience helped us even after the curtain went down. We asked for questions and reactions after every performance, and our conversations with the audience raised provocative issues about the traditional roles of men and women. (My favorite question from a seven-year-old girl in the second row: "Why did Eve eat the apple?" Gleeful laughter from the audience. Answer: "Is that your daddy next to you?" "Yes." "Ask him.")

Twain is a brilliant writer, a master at making universal human connections. The final effect of these two stories as played together the last written when Twain himself was suffering deeply is, I think, to provide a kind of benediction, a celebration of not only his own marriage but also of that mysterious bond created by man and woman together, in love, over a lifetime.

The last entry in Adam's "Diary," added sometime after its completion, rqads, in its entirety, "At Eve's grave: Wheresoever she was, there was Eden." Adam has come full circle. Filled with a final realization of his love for Eve, he simply and eloquently voices that love in terms of lost perfection. This lyrical tone contrasts with the dark quality of much of Twain's writing at the time, most notably The Mysterious Stranger, which ends with cosmic laughter echoing through the universe, a laughter at the folly of human endeavor in the face of the bleak indifference of the void. The "Diaries" are a grace, a respite from pain.

I, don't think I could have begun this journey, this look at Twain and his own journey from love to loss and reconciliation, without the experience of Dartmouth. Harry Bond, the man and the teacher, was a part of that. Chairman of the English Department, a scholar and a deeply compassionate man, he was an extraordinary teacher, one who was capable of changing a student's life in the most profound way. He had fought in World War II as an infantry officer in the Italian campaign, and he was one of the first to walk through the gates of the concentration camps an experience that marked him, and through him, many of us, for life. His field was Renaissance literature, and he was committed to the view, most movingly expressed in his class, that art is more than an aesthetic event; great art is a moral event as well, it is connected to who and why we are. Which brings us again to Twain.

After performing the work at Dartmouth, we took it to Trinity University, which taped it. A friend showed the tape to Lindsay Law, the executive producer at American Playhouse, who asked us to produce the piece for PBS. Several months later we taped "The Diaries of Adam and Eve" at Dallas's Plaza Theatre. Our Eden was a garden of Twain's period, an ornamented gazebo with benches of wrought-iron scrollwork. Ruling out fig leaves, we wore costumes that were a blend of contemporary and period. (A good choice as it turns out; Meredith broke her ankle a week before rehearsals the long dress hides her walking cast.)

Although the final PBS performance was shot in Texas, the play is, I feel, really Dartmouth's own, a kind of gift to the public by the College. Although it is not "King Lear," it does, in its small way, embody the high purpose of a great college or university: through its graduates it keeps alive our artistic and spiritual heritage and seeks to pass it on, to transmit that heritage to the nation as a whole. I was pleased to play a part in that most valuable process, to pass on a part of Dartmouth's gift to me.

Actor David Birney lives in Los Angeles.

"The play is, I feel, really Dartmouth's own, a kind of gift to the public by the College."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

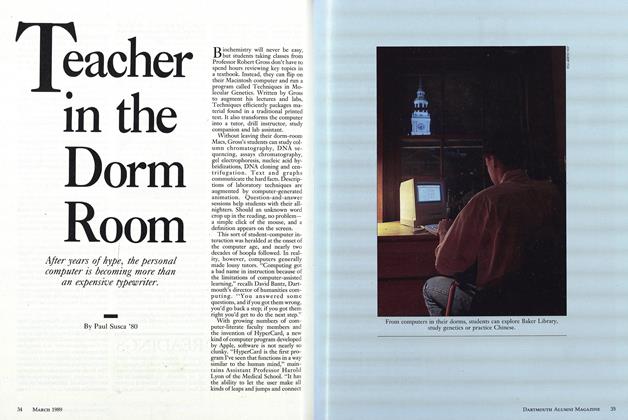

Cover Story

Cover StoryTeacher in the Dorm Room

March 1989 By Paul Susca '80 -

Feature

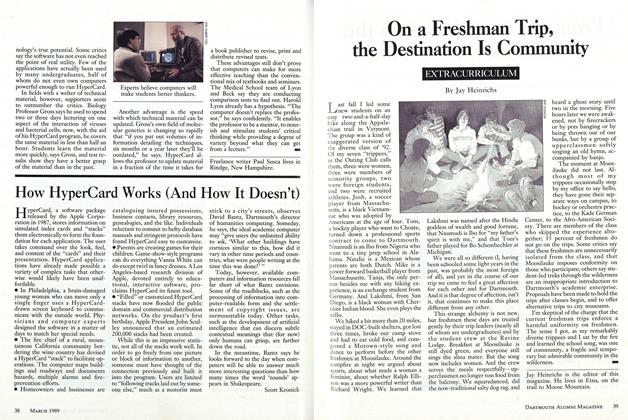

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

March 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureWhy I Traded Basketball for Biology

March 1989 By Liz Walter '89 -

Article

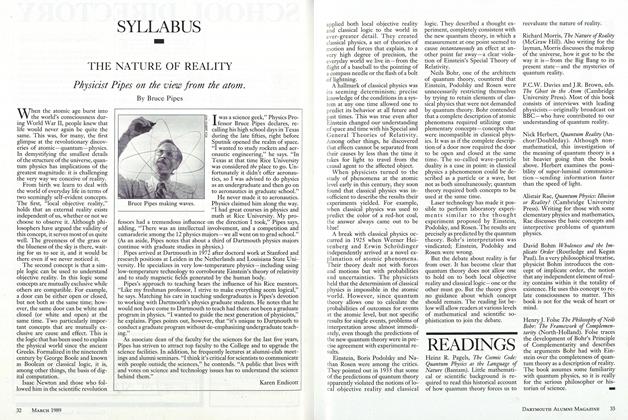

ArticleTHE NATURE OF REALITY

March 1989 By Bruce Pipes, Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOROZCO'S LEGACY

March 1989 -

Article

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

March 1989

David Birney '61

Features

-

Feature

FeatureOur Way in the World: A Conversation with John Dickey

January 1976 -

FEATURES

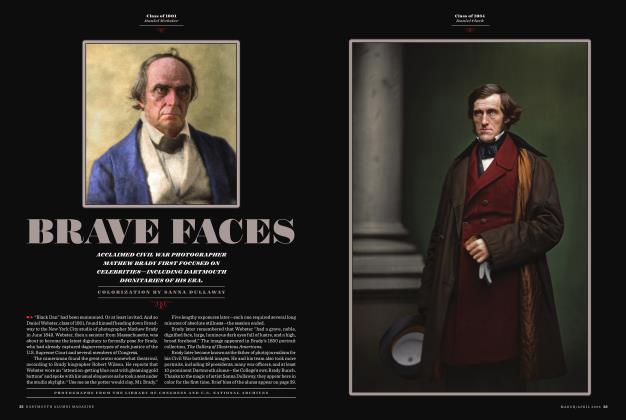

FEATURESBrave Faces

APRIL 2025 -

Feature

FeatureEat Here

February 1992 By CHRIS WALKER '92 and TIG TILLINGHAST '93 -

Feature

Feature"Fraternities Are in Trouble"

MARCH 1972 By DAVID WRIGHT '72 -

Feature

FeatureDARTMOUTH SONGS

APRIL 1963 By HAROLD F. BRAMAN '21 -

Feature

FeatureWelcome to the dark places

JAN.- FEB. 1982 By Rob Eshman