EXTRACURRICULUM

Last fall I led some new students on an easy two-and-a-half-day hike along the Appalachian trail in Vermont. The group was a kind of exaggerated version of the diverse class of '92. Of my seven "trippees," as the Outing Club calls them, three were women, three were members of minority groups, two were foreign students, and two were recruited athletes. Josh, a soccer player from Massachusetts, is a black Vietnamese who was adopted by Americans at the age of four. Tom, a hockey player who went to Choate, turned down a professional sports contract to come to Dartmouth. Nnamudi is an Ibo from Nigeria who went to a tiny prep school in Alabama. Natalie is a Mexican whose parents are both Dutch. Mike is a power forward basketball player from Massachusetts. Tanja, the only person besides me with any hiking experience, is an exchange student from Germany. And Lakshmi, from San Diego, is a black woman with Cherokee Indian blood. She even plays the cello.

We hiked a bit more than 20 miles, stayed in DOC-built shelters, got lost three times, broke our camp stove and had to eat cold food, and composed a Motown-style song and dance to perform before the other freshmen at Moosilauke. Around the campfire at night we argued about sports, about what made a woman a feminist, about whether Ralph Ellison was a more powerful writer than Richard Wright. We learned that Lakshmi as named after the Hindu goddess of wealth and good fortune, that Nnamudi is Ibo for "my father's spirit is with me," and that Tom's father played for Bo Schembechler at Michigan.

We were all so different (I, having been schooled some light years in the past, was probably the most foreign of all), and yet in the course of our trip we came to feel a great affection for each other and for Dartmouth. And it is that degree of affection, isn't it, that continues to make this place different from any other.

This strange alchemy is not new, but freshmen these days are treated gently by their trip leaders (nearly all of whom are undergraduates) and by the student crew at the Ravine Lodge. Breakfast at Moosilauke is still dyed green, and everyone still sings the alma mater. But the song now includes women. And the crew serves the meals respectfully upperclassmen no longer toss food from the balcony. We squaredanced, did the now-traditional salty dog rag, and heard a ghost story until two in the morning. Five hours later we were awakened, not by firecrackers or by pots banging or by being thrown out of our bunks, but by a group of upperclassmen softly singing an old hymn, accompanied by banjo.

The moment at Moosilauke did not last. Although most of my trippees occasionally stop by my office to say hello, they have gone their separate ways on campus, to hockey or orchestra practice, to the Kade German Center, to the Afro-American Society. There are members of the class who skipped the experience altogether; 15 percent of freshmen do not go on the trips. Some critics say that these freshmen are unnecessarily isolated from the class, and that Moosilauke imposes conformity on those who participate; others say student-led treks through the wilderness are an inappropriate introduction to Dartmouth's academic enterprise. Proposals have been made to hold the trips after classes begin, and to offer alternative trine to museums.

I'm skeptical of the charge that the current freshman trips enforce a harmful uniformity on freshmen. The sense I got, as my remarkably diverse trippees and I sat by the fire and learned the school song, was one of community, a fragile and temporary but admirable community in the wilderness.

Jay Heinrichs is the editor of this magazine. He lives in Etna, on the trail to Moose Mountain.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureFrom Dartmouth Comes the World's First Love Story

March 1989 By David Birney '61 -

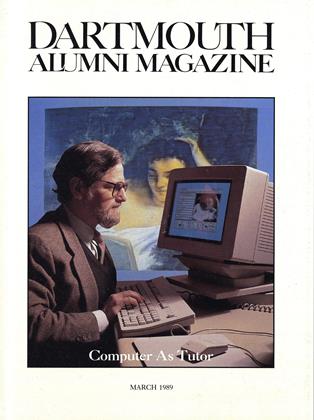

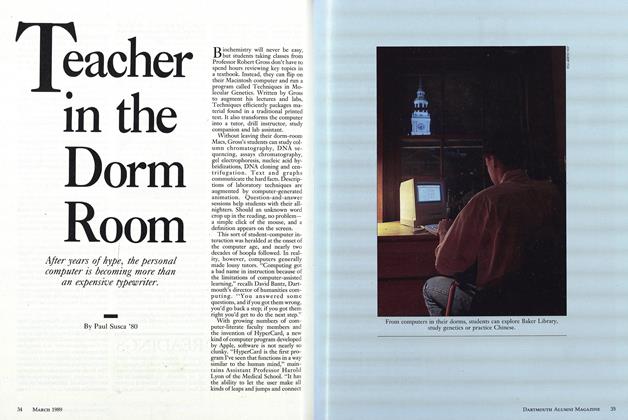

Cover Story

Cover StoryTeacher in the Dorm Room

March 1989 By Paul Susca '80 -

Feature

FeatureWhy I Traded Basketball for Biology

March 1989 By Liz Walter '89 -

Article

ArticleTHE NATURE OF REALITY

March 1989 By Bruce Pipes, Karen Endicott -

Article

ArticleOROZCO'S LEGACY

March 1989 -

Article

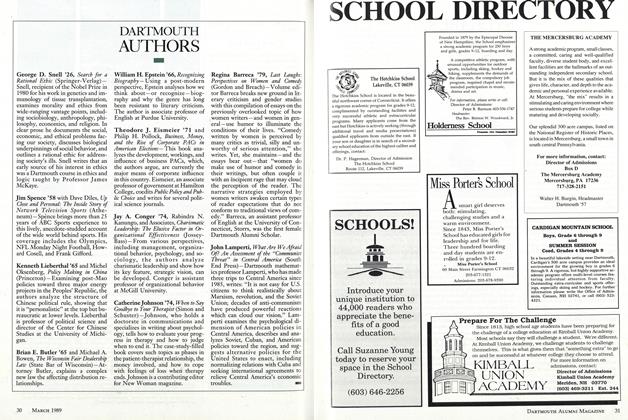

ArticleDARTMOUTH AUTHORS

March 1989

Jay Heinrichs

-

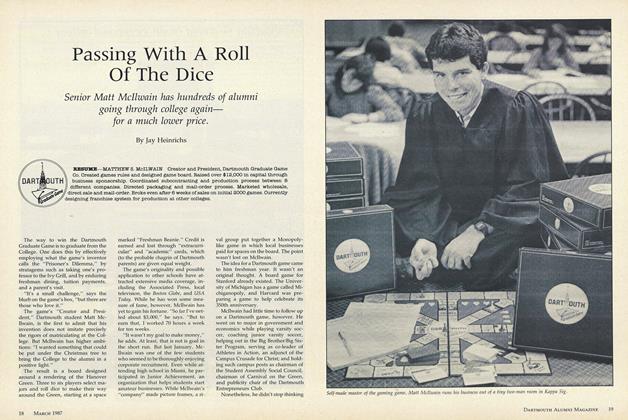

Cover Story

Cover StoryPassing With A Roll Of The Dice

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Scholar President

June 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

MAY • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleBeyond Scrapbook

May 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleYour Breath Smells So Bad People on the Phone Hang Up.

November 1994 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleNels Comes Home

April 1995 By Jay Heinrichs

Features

-

Feature

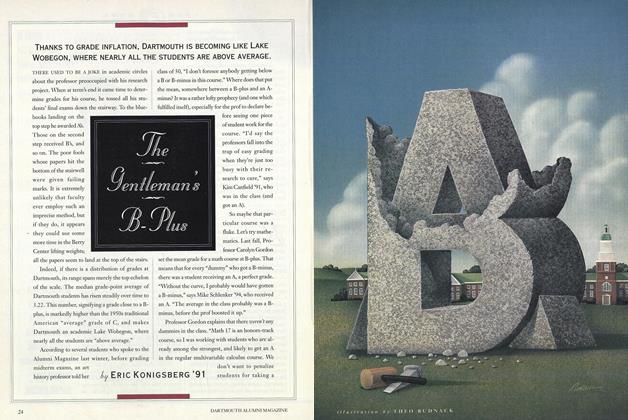

FeatureThe Gentleman's B-Plus

February 1992 By Eric Konigsberg '91 -

Feature

FeatureJOHN THORNTON OF CLAPHAM

OCTOBER 1968 By FRANK W. FETTER -

Feature

FeatureCOACHES

SEPTEMBER 1996 By JIM COLLINS '84 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryOught Ought

NOVEMBER 1996 By Joe Mehling '69 -

Feature

FeatureThe Road Not Taken

April 1977 By JOHN S. MAJOR -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

Nov/Dec 2007 By Kristin Brenneman '97