If the football team works as hard as our sports editor, an Ivy title is a lead-pipe cinch.

People always hear that the athletes on the football team have been "in the weight room," and they nod solemnly, as though being there is some sort of magic balm that, once applied, produces ferocious footballers.

Well, just being in the weight room doesn't make you a great football player any more than being in the garage makes you a Ferrari. I decided to find out for myself what happens there—which, for me, was a daunting prospect. After all, I'm a sportswriter, a profession I enjoy because, as the saying goes, it involves very little heavy lifting.

Nonetheless (anything for a story), last year I signed up for the same weight-training program that the players follow in the offseason. I did it not once but twice: 12 weeks' worth from October to January and from February to May.

What value is weight training to a football team? When Buddy Teevens '79 inherited it, there was no set workout program. He can't technically make it mandatory under Ivy League rules, but like every other coach in the league, Buddy has made it clear to his players that if they want to play, they have to lift. As a result, last year's team went 5-5, the first non-losing season in six years. And Buddy will be the first to tell you that the workouts have played a large role in the team's resurgence.

The program that the Big Green gridders use is based on free weights, with some Nautilus machines added where necessary. Buddy is a big believer in this for one very simple reason: football is a collision sport, and only free-weight training gives what he feels is adequate preparation for the violence inherent to the game. "So many things are different with free weights," Buddy explains. "You have to use your strength not just to move the weight but to balance it, control it, and get a full range of motion in each exercise. Nautilus is great for a lot of muscle groups, which is why we use it for legs and the neck. But it only asks you to work in one plane. Football is not played in one plane."

My program started with a visit to Glenn Pires, who used to coach inside linebackers and oversee the weight-training program. (He has since left the College to take a similar position. at Syracuse University.) Pires handed me a surprisingly thick manual—35 pages of philosophy and instruction on weight training, stretching, running, nutrition, and plyometrics, which are specific muscle-building exercises that mostly involve jumping in various directions and he walked me through my first workout.

I don't run. I refuse. But I substituted the stationary bike for running. As for plyometrics, I couldn't do them. The manual says if you cannot lift twice your body weight in the "squat" (in which you hold the barbell over your neck and push off with your legs), you don't have the strength necessary to benefit from plyometrics. I knew one thing right off: the only way I could move twice my weight in any direction was with a forklift.

There are two exercises that really count when it comes to free weights: the bench press and the squat. The best bench on the team is done by offensive lineman Harris Siskind '90, who can move some 440 pounds. The team average is more than 300 pounds. And me? When I started, I could lift all of 110 pounds. The squat takes care of the lower body. Running back David Clark '90 has the laurels here, with a personal best of more than 600 pounds. I could move 150 pounds on the first try. Pathetic? That's easy for you to say.

Four days a week, I went to the weight room on my lunch hour. Every week, a litde more weight, and a different number of "reps," or repetitions. As the weight you lift increases, the number of times you actually move it decreases. You also vary exercises in order to develop different muscle groups and break up the monotony.

Two very important lessons came out of my lifting:

• Electric shock helps your training. There's an incredible amount of static electricity in the astroturf which carpets the Dartmouth weight room, and whenever you touch a bar or anything metallic, you get a little jolt. I like to think of it as the thing that may just make the difference between an Ivy title and second place.

• Heavy metal music exists to lift weights by. There's just something about the screams of a group like Guns 'N' Roses that really gets you angry and makes you want to push that weight.

As I finished the first cycle of lifting, I noticed some good results. I was thinner, stronger, and definitely "tighter." That, in fact, was the description most of my friends used to describe the changes I underwent. Now I had strength and some firmness, where before I felt like a not-quitedone dinner roll.

At the end of spring term, I comfortably benched 225 pounds five times and squatted 310 five times. I am now half as strong as Harris Siskind in the bench and half as strong as David Clark in the squat. I can go 25 minutes on the stationary bike. I even followed the nutrition part—less fat and red meat, more carbohydrates.

Buddy reports that many incoming freshmen already have solid weight-training experience from high school. Today's players spend a lot more time in the weight room than ever before. I spend time there now myself. I don't plan to quit.

This program, which carries a risk of injury, isn't for everyone. In fact, for the general, health-conscious public, Nautilus is probably still the safest route. But if you plan to involve yourself in a violent collision sport (and the aggressive sportswriter never knows when he'll collide with somebody), you need free weights to survive.

Just get ready to like Guns 'N' Roses. I think it's mandatory.

BEFORE Myself as an uncooked dinner roll. When I suggested a story on the football team's weighttraining program, the editor snickered, "Hey, Chuck, are you sure you're fit to do that story?" My choice was either to shoot the editor or go through the program myself.

AFTER I went through the program. Okay, so I don't look that different. Some people work out very little and look as though they were cut from marble. Me, I just look a bit tighter. But when I hulked into the editor's office and flexed, he let me do the story.

just when we got ourselves a compact, efficient model in a sports editor, Chuck Young '88 left his part-time jobs at the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine and the Sports Information Service to write for the Concord Monitor.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBoredom's Uses

October 1989 By Joseph Brodsky -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDon't Call It "The D"

October 1989 By Michael T. Reynolds '90 -

Feature

FeatureAfter the Massacre

October 1989 By Jessica Smith '89 -

Feature

FeatureBUBBLE AND PEAK

October 1989 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1989 -

Sports

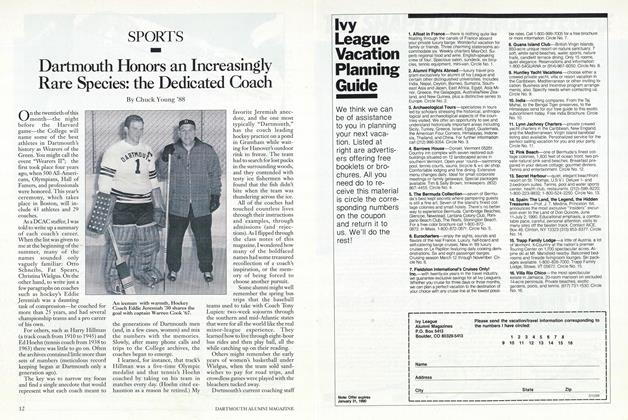

SportsDartmouth Honors an Increasingly Rare Species: the Dedicated Coach

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88

Chuck Young '88

Features

-

Feature

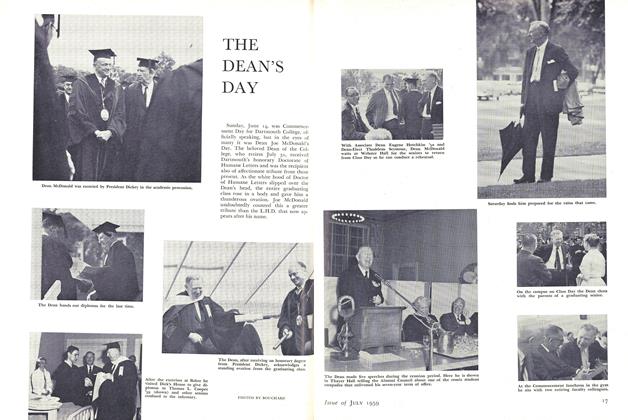

FeatureTHE DEAN'S DAY

JULY 1959 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni Awards

FEBRUARY 1971 -

Feature

FeatureMonitoring Nature's Big Blow-Up

September 1980 By Dan Nelson -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHOW TO HUCKTHE DISC

Sept/Oct 2001 By ERIC ZASLOW '89 -

Feature

FeatureA CHANCE FOR THE PENTAGON TO HELP SOLVE SOME DOMESTIC AS WELL AS MILITARY PROBLEMS

MAY 1970 By GERALD G. GARBACZ '58 -

Feature

FeatureThe Onlyness of a Long-Distance Runner

June 1994 By Robert Sullivan '75