On a Beijing campus, people adjust to the horror.

The full impact of what had happened didn't sink in until Monday evening, three days after the shooting started. While I was waiting for dinner at the Sheraton, Kate Phillips came over to tell me that a mutual friend had put a note under her door. It read: "Two of my friends are dead. Please tell the world."

Even then it took a few minutes for those words to sink in, words that affected me more than the sound of tanks and guns had. We were all in a state of shock, having been up all of Saturday night counting the tanks and armored personnel carriers of China's People's Liberation Army that rolled west on Changan Avenue, in front of the Beijing Hotel where I had been staying and toward the square.

Throughout Sunday occasional shots could still be heard* as well as the booms from the engines of public buses burned and smashed by people still on the streets.

But by Monday very few people remained outside. In less than two days, the crazed and exhilarated defiance that had charged Beijing for six weeks was crushed, silenced.

ran into a senior who had been active in the demonstrations. "What are you doing here?" I asked him. "Aren't you afraid you'll be arrested?" About two weeks later I returned to the Beijing Normal University campus to pick up some things from my room and to contact some people. It was very quiet, but not quite deserted. Thinking I'd gone back to the States, everyone from the housekeepers at the empty foreigners' dorm to the English Department chair was ecstatic to see me. "See how calm it is here?" they said. "No problems, everything's calm." Indeed, it was very calm, like an early summer vacation. Freshmen, sophomores, and juniors had all gone home. Final exams and missed work would have to be made up this fall. I

"No," he replied calmly. He, like the other seniors at B.N.U., one of the most active schools in the movement, was allowed to graduate and receive his diploma, but he couldn't return home until he had completed a "Political Study Class."

"What do you do in those classes?"

My friend replied that he and his fellow seniors had to read Deng Xiaoping's speech and the speeches made at the Party Congress in which the party leadership was reshuffled immediately after the crackdown. They had to write papers on them, listen to lectures, and attend discussions. They had to write an article on their recent experiences. My friend said they all wrote that they had been exploited by Fang Lizhi, a prominent dissident holed up in the U.S. embassy, and Wu'er Kaixi, a prominent student leader now in the United States. "It doesn't matter. They're both safe. We all just write this. It's all lies. They can't see what we really are thinking." It doesn't matter. Nothing really matters. The phrases were to come up a lot in conversations to come.

I passed another student on the path, an older woman who appeared particularly pleased to see me, clasping my hand and saying how worried the class had been when Kate and I stopped coming. We talked while she walked her bike in the direction of my dormitory. At one point she stopped, looked around briefly and continued walking. I asked her if she were nervous, and what she thought would happen in Beijing. Much more emotional than the first student I had seen, she shook her head and frowned, saying she was nervous and that the situation wasn't good. Everyone was just keeping silent now, she added. I asked if she knew how many B.N.U. students had been killed. She said not as many as people had thought at first. "Many students we thought were dead returned to campus a few days later. Here, three students were killed."

"How many students were killed in all?"

She shook her head. "We don't know. Perhaps we will never know the truth. Perhaps we will only know in many years. You know, many citizens were killed, many more than students, and it will be very difficult to find out how many really died."

EDITOR'S NOTE: Last spring, a manuscript was faxed to us from China by Jessica Smith 'B9 and Kate Phillips '89, English instructors at Beijing Normal University. The essay described the treatment of intellectuals in that country, where academics are paid (poorly) by the word.

Shortly after the fax arrived, students went on strike in Tienanmen Square. Smith, who had been a history-Asian Studies major at Dartmouth, was freelancing as an interpreter for the Cable News Network during Mikhail Gorbachev's visit, and continued working for CNN during the demonstrations and the crackdown. She checked in with us afterward, and we asked her to tell what it was like to be in Beijing after the soldiers stopped shooting.

Smith has had her one-year contract renewed at Beijing Normal, and she has continued to teach there.

I happened upon one more student, also an employee at B.N.U. I hadn't known until then that her boyfriend had been very active in the movement. A few days before the massacre, he had been one of four well-known figures who had resumed the hunger strike. I greeted her with the usual "How are you?" (The übiquitous phrase had taken on new meaning. Another greeting had become popular among students: "Hey! Still alive?")

In a noticeable break from the usual Chinese habit of glossing over personal problems, my student hesitated for a moment and replied directly: "Not good." Her boyfriend had been arrested.

The day I left I had lunch with a teacher, a man in his fifties who occasionally tutored me and is planning to spend the year at Dartmouth. I hiked to his apartment in one of the campus housing blocks. His wife answered the door, her usual smiling self, and ushered me into the dining/ sitting/TV room/office, where my teacher emerged, looking disheveled and nervous. He pulled me over to his desk and showed me a thick envelope his plane tickets to Hanover. He seemed torn between happiness and dread that some pointless and arbitrary hitch would prevent him from leaving. He commanded me to eat while he finished filling out some forms. His son and wife joined us.

Their attitude was like that of many people who had not been direcdy involved in the movement. Unlike the younger students, for whom the last six weeks had been earthshaking and then earthshattering, many Chinese seemed to regard the government crackdown as if it were a natural disaster, like a flood-earthshaking, yes, and there's damage and people are killed, but it will pass. All one can do for now is to sit safely at home, avoid the floodwaters, and try to get on with life under the circumstances.

For, like a flood, student protests, by crackdowns. During Mao Zedong's time, there were "anti-rightist" purges, and in Deng Xiaoping's reign there have been periodic campaigns against "spiritual pollution" and "bourgeois liberalization." purges, and crackdowns have happened before. Demonstrations and rallies with more than 100,000 people were commonplace during the Cultural Revolution. Conspicuous paralels have been drawn between this "incident" and the 1976 Tienanmen Incident, in which violence followed defiance of a government order not to lay wreaths in the Square for the late Premier Zhou Enlai. Student protests, including hunger strikes, occurred in 1980 and in 1986. Both were followed

I'd only read about these, however. In my own mind, the only China I knew was "open China"—a China with Cokes, Kentucky Fried Chicken, and Adidas sweatshirts and Beijingers who didn't stare at foreigners so much (though you could still find a really good open-mouthed stare if you traveled outside Beijing). No matter how much I try to put the spring's events into the context of "cycles" or "repeated history," it was still, well, I don't think the word "shock" really describes it.

Besides, I think that this time really was different from the others. Not only because this spring saw the largest anti-government demonstrations since the founding of the People's Republic, and not only because the tanks were rolled out to crash people. This time was different because, for the first time, the events were recorded and exported to the rest of the world by the latest media technology. When I came back to the U.S. for a few weeks in the summer, I was surprised at how much anger and concern had been stirred up among Americans. I was especially astonished to hear that this year's Dartmouth graduates at Commencement wore white armbands in memory of those who died in and around Tienanmen Square.

This year may be different for another reason: China's real leaders are very, very old, and the country could be nearing the end of a dynasty. Of course, the old leaders may be able to find some new, technocratic blood to keep things going, and the recent events may have been just another crackdown. Personally, I think we'll see change, but I'd better not say it too loudly or I may not get my job back next year . . .

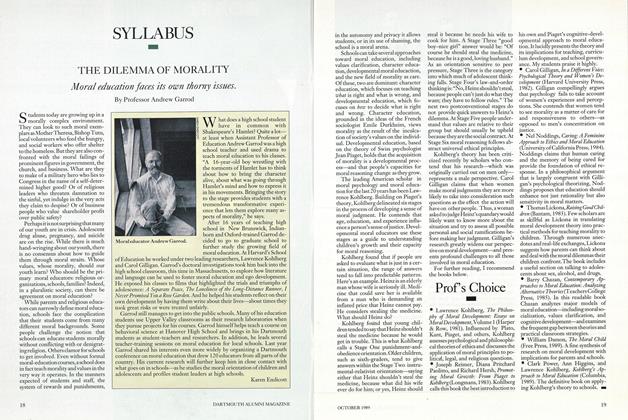

The "cleanup" of China extended beyond Tienanmen Square. Student demonstrators were forced to write papers saying they had been misled by their leaders.

"Many Chinese seemedto regard thegovernmentcrackdown as if itwere a naturaldisaster."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureBoredom's Uses

October 1989 By Joseph Brodsky -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDon't Call It "The D"

October 1989 By Michael T. Reynolds '90 -

Feature

FeatureHow I Started Writing Muscular Prose

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88 -

Feature

FeatureBUBBLE AND PEAK

October 1989 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1989 -

Sports

SportsDartmouth Honors an Increasingly Rare Species: the Dedicated Coach

October 1989 By Chuck Young '88

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTRUSTEES SANCTION A FOURTH TERM

OCTOBER 1962 -

Cover Story

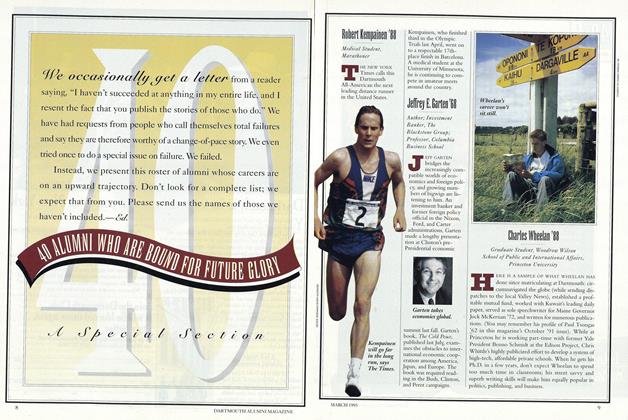

Cover Story40 ALUMNI WHO ARE BOUND FOR FUTURE GLORY

March 1993 -

Feature

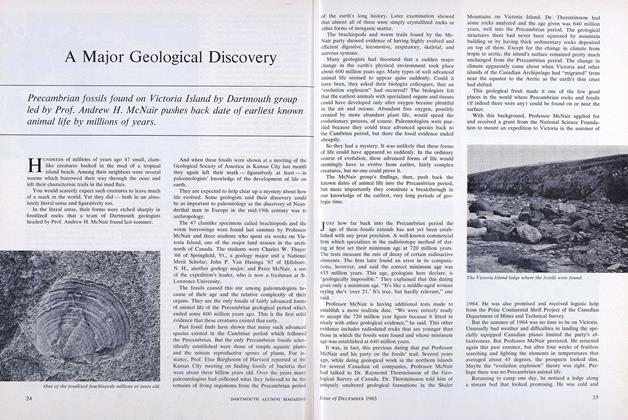

FeatureA Major Geological Discovery

DECEMBER 1965 By GEORGE O'CONNELL -

Feature

FeatureELECTRIC BODY LANGUAGE

SEPTEMBER 1991 By JAY HEINRICHS -

Feature

FeatureThe Hollywood Connection

November 1982 By Maury Rapf '35 -

Feature

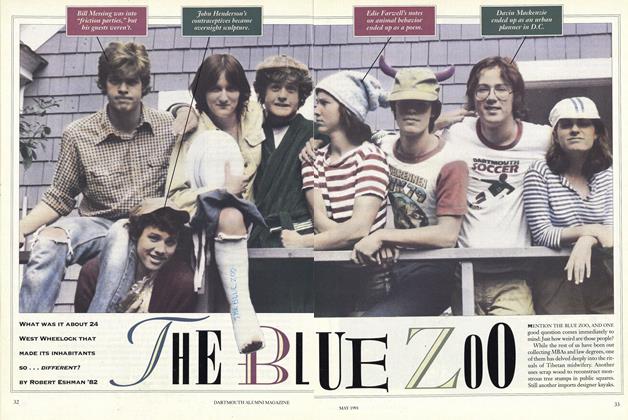

FeatureTHE BLUE ZOO

MAY 1991 By Robert Eshman '82