Conductor O'Neal on masterworks for the voice and soul.

Music joined with text is one of the most potent forms of communication available to a composer. Not surprisingly, composers usually set texts that are of cultural significance or profound sentiment. For example, in opera, the main form of secular vocal-orchestral music since the seventeenth century, composers tend to dramatize historical, epic, or mythical stories. Traditional religious texts most notably the Catholic Mass, the Passion (the story of the betrayal and crucifixion of Christ), and the Requiem (the Masscommemorating the departed) form the basis of the sacred genre of choral-orchestral music.

Many of the traditional sacred texts have undergone numerous musical treatments over the centuries. Yet, despite the repetitions, distinguished composers manage to bring start lingly fresh perspectives to thewords through their individual musical approaches. This is evident if we compare, for example, Bach's setting of the text "Dona nobis pacem" the plea to "Grant us peace" in his Massin B minor, with settings composed by two of his successors, Haydn and Beethoven.

Bach uses the same music for the "Dona nobis pacem " text that he composed for the earlier section " Gratias agimus tibi " ("We give you thanks for your great glory"). The music, which consists of two contrasting themes woven together into an arch-like structure, creates a monumental musical edifice that ties together the text's multiple messages of thanks, the glory of God, and peace.

By contrast, Haydn's treatment of the same text in the Lord Nelson Mass consists of a progression from a tone of imploration for peace to one of jubilant celebration, as though peace has been realized. There is no reprise of familiar music, only forward intensification toward an ecstatic conclusion.

In his Mass in C Major, Beethoven, like Bach, uses the idea of musical recall in his "Dona nobis pacem" setting, but in quite a different way. The music he recalls is not from the "Gratias" section but from the opening measures of the first movement, "Kyrie eleison" ("Lord, have mercy") Beethoven intends for the listener to be transformed, just as Bach and Haydn did. Here, however, the final plea for peace is musically synonymous with the initial plea for mercy. Considering all that transpires in between, both become all the more poignant.

Bringing the musical page to life through performance is a challenge of the highest order. Recent research by music historians into the earliest performances of works has invigorated debate about what is commonly referred to as performance practice choices about such musical elements as the use of authentic or modern instruments, the size and type of performance hall, tempi, dynamics, articulations, vocal timbre and character. Many musicians are trying to recapture the scale and style of the composers' own performances of their work, while for others authenticity is and traditionally was of little concern. For example, to the organizers of a 1784. commemorative performance of Handel's Messiah in Westminster Abbey, bigger was better. An orchestra of 251 and a chorus of 275 performed, even though Handel's original performance probably featured only 31 players and 40 singers. The idea for later nineteenth century inflations perhaps began with this event or with Mozart's influential rescoring of Messiah which added clarinets, flutes and trombones where they had not even existed in the original score. But deciding what Handel's true intentions were has not been easy, for the composer himself changed the score numerous times.

The list below consists of a few representative works from the vast range of choral-orchestral music. Common to all is my ultimate criterion for judging a performance: the music must move the heart and the mind.

Melinda O'Neal

Despite the intimate knowledge of a musical work that comes from months of studying and rehearsing a score, choral conductor and music professor Melinda O'Neal finds that there can still be surprises at concert time. "The beauty of the music and the text can hit me like a two-by-four," she says. "It can take me a week to recover after a concert."

O'Neal first felt the impact of vocal music during childhood, when a neighbor introduced her to the folk music of Peter, Paul and Mary. " I loved their harmonies, the color of their sound, their unique way of communicating," she recalls. Guitar in hand, O'Neal grew up organizing hootennanies for her friends and performing in Bethesda , Maryland.

"But," she recalls, "I realized as a performer that there was something missing. I wanted to find out what makes music irresistible for me. I simply needed to know more." After undergraduate work in choral music education at Florida State University and a stint of teaching music in public school, she went on to Indiana University's graduate program in choral conducting. Her doctoral dissertation was a conductor's analysis for performance of Berlioz's L'Enfance du Christ. (She recommends conductor John Elliot Gardiner's compact disks Erato ECD 75333.)

For nine years O'Neal has directed Dartmouth's 120-member Handel Society Chorus of community and student singers, and the Chamber Singers undergraduate ensemble. To each group she brings her dual interests in music education and performance. "You are building an instrument when you have a chorus,"she explains. "You build it through rehearsals not just teaching the notes, but shaping the voices, helping the singers discover what the music means. You help a group grow into the music."

O'Neal, who currently chairs the music department and heads up the music foreign study program in London, says that as a conductor she "must be a reflection of the composer and the music." But music mirrors her own ideas as well. "Music is one of the humanizing elements of life," she says. "For me it's important to share music through making it."

Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

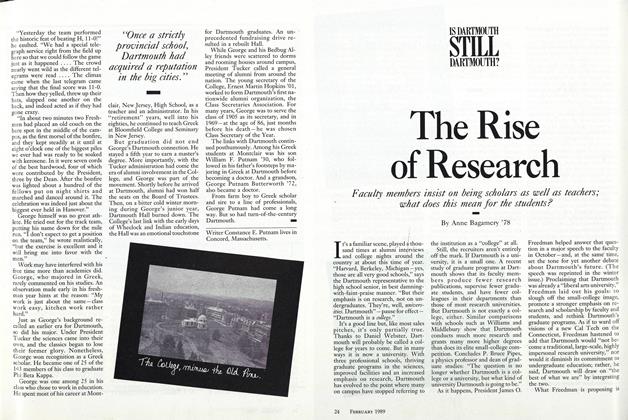

Cover StoryThe Rise of Research

February 1989 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

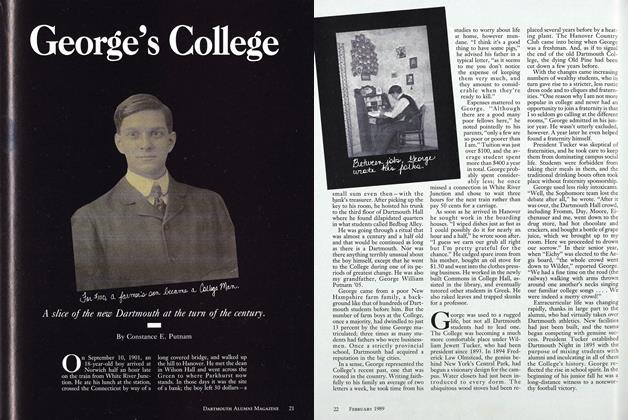

FeatureGeorge's College

February 1989 By Constance E. Putnam -

Feature

FeatureA Story of Drama, Fierce Competition, Mom and Apple Pie

February 1989 By George Canizares -

Article

ArticleREVIEW STUDENTS ARE BACK

February 1989 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1988

February 1989 By Chuck Young -

Article

ArticleThe Battle Against AIDS

February 1989 By Martha Hennessey '76