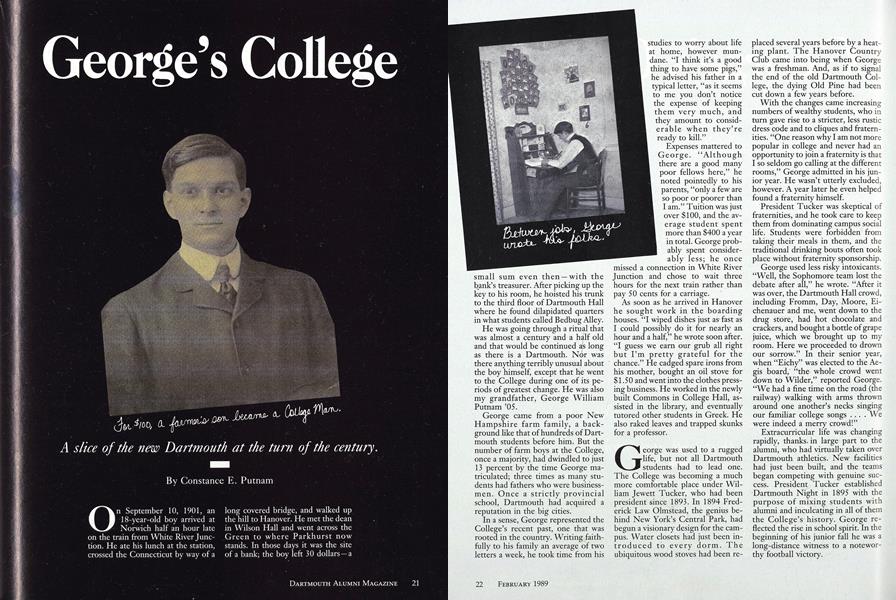

A slice of the new Dartmouth at the turn of the century.

On September 10, 1901, an 18 year-old boy arrived at Norwich half an hour late on the train from White River Junction. He ate his lunch at the station, crossed the Connecticut by way of a long covered bridge, and walked up the hill to Hanover. He met the dean in Wilson Hall and went across the Green to where Parkhurst now stands. In those days it was the site of a bank; the boy left 30 dollars a small sum even then with the bank's treasurer. After picking up the key to his room, he hoisted his trunk to the third floor of Dartmouth Hall where he found dilapidated quarters in what students called Bedbug Alley.

He was going through a ritual that was almost a century and a half old and that would be continued as long as there is a Dartmouth. Nor was there anything terribly unusual about the boy himself, except that he went to the College during one of its periods of greatest change. He was also my grandfather, George William Putnam '05.

George came from a poor New Hampshire farm family, a background like that of hundreds of Dartmouth students before him. But the number of farm boys at the College, once a majority, had dwindled to just 13 percent by the time George matriculated; three times as many students had fathers who were businessmen. Once a strictly provincial school, Dartmouth had acquired a reputation in the big cities.

In a sense, George represented the College's recent past, one that was rooted in the country. Writing faithfully to his family an average of two letters a week, he took time from his studies to worry about life at home, however mundane. "I think it's a good thing to have some pigs," he advised his father in a typical letter, "as it seems to me you don't notice the expense of keeping them very much, and they amount to considerable when they're ready to kill."

Expenses mattered to George. "Although there are a good many poor fellows here," he noted pointedly to his parents, "only a few are so poor or poorer than I am." Tuition was just over $100, and the average student spent more than $400 a yearin total. George probably spent considerably less; he once missed a connection in White River Junction and chose to wait three hours for the next train rather than pay 50 cents for a carriage.

As soon as he arrived in Hanover he sought work in the boarding houses. " I wiped dishes just as fast as I could possibly do it for nearly an hour and a half," he wrote soon after. " I guess we earn our grub all right but I'm pretty grateful for the chance." He cadged spare irons from his mother, bought an oil stove for $1.50 and went into the clothes pressing business. He worked in the newly built Commons in College Hall, assisted in the library, and eventually tutored other students in Greek. He also raked leaves and trapped skunks for a professor.

George was used to a rugged life, but not all Dartmouth students had to lead one. The College was becoming a much more comfortable place under William Jewett Tucker, who had been president since 1893. In 1894 Frederick Law Olmstead , the genius behind New York's Central Park, had begun a visionary design for the campus. Water closets had just been introduced to every dorm. The ubiquitous wood stoves had been replaced several years before by a heating plant. The Hanover Country Club came into being when George was a freshman. And, as if to signal the end of the old Dartmouth College, the dying Old Pine had been cut down a few years before.

With the changes came increasing numbers of wealthy students, who in turn gave rise to a stricter, less rustic dress code and to cliques and fraternities. "One reason why I am not more popular in college and never had an opportunity to join a fraternity is that I so seldom go calling at the different rooms," George admitted in his junior year. He wasn't utterly excluded, however. A year later he even helped found a fraternity himself.

President Tucker was skeptical of fraternities, and he took care to keep them from dominating campus social life. Students were forbidden from taking their meals in them, and the traditional drinking bouts often took place without fraternity sponsorship.

George used less risky intoxicants. "Well, the Sophomore team lost the debate after all," he wrote. "After it was over, the Dartmouth Hall crowd, including Fromm, Day, Moore, Eichenauer and me, went down to the drug store, had hot chocolate and crackers, and bought a bottle of grape juice, which we brought up to my room. Here we proceeded to drown our sorrow." In their senior year, when " Eichy" was elected to the Aegis board, "the whole crowd went down to Wilder," reported George. "We had a fine time on the road (the railway) walking with arms thrown around one another's necks singing our familiar college songs .... We were indeed a merry crowd!"

Extracurricular life was changing rapidly, thanks, in large part to the alumni, who had virtually taken over Dartmouth athletics. New facilities had just been built, and the teams began competing with genuine success. President Tucker established Dartmouth Night in 1895 with the purpose of mixing students with alumni and inculcating in all of them the College's history. George reflected the rise in school spirit. In the beginning of his junior fall he was a long-distance witness to a noteworthy football victory.

"Yesterday the team performed the historic feat of beating H, 11-0!" he exulted. "We had a special telegraph service right from the field up here so that we could follow the game just as it happened .... The crowd nearly went wild as the different telegrams were read .... The climax came when the last telegram came saying that the final score was 11-0. Then how they yelled, threw up their hats, slapped one another on the back, and indeed acted as if they had gone crazy.

"In about two minutes two Freshmen had placed an old couch on the bare spot in the middle of the campus, as the first morsel of the bonfire, and they kept steadily at it until at eight o'clock one of the biggest piles we ever had was ready to be soaked with kerosene. In it were seven cords of the best hardwood, four of which were contributed by the President, three by the Dean. After the bonfire was lighted about a hundred of the fellows put on night shirts and marched and danced around it. The celebration was indeed just about the biggest ever held in Hanover."

George himself was no great athlete. He tried out for the track team, putting his name down for the mile ran. "I don't expect to get a position on the team," he wrote realistically, "but the exercise is excellent and it will bring me into favor with the men."

Work may have interfered with his free time more than academics did. George, who majored in Greek, rarely commented on his studies. An observation made early in his freshman year hints at the reason: "My work is just about the same class work easy, kitchen work rather hard."

Just as George's background recalled an earlier era for Dartmouth, so did his major. Under President Tucker the sciences came into their own, and the classics began to lose their former glory. Nonetheless, George won recognition as a Greek scholar. He became one of 25 of the 143 members of his class to graduate Phi Beta Kappa.

George was one among 25 in his class who chose to work in education. He spent most of his career at Mount clair, New Jersey, High School, as a teacher and an administrator. In his "retirement" years, well into his eighties, he continued to teach Greek at Bloomfield College and Seminary in New Jersey.

But graduation did not end George's Dartmouth connection. He stayed a fifth year to earn a master's degree. More importantly, with the Tucker administration had come the era of alumni involvement in the College, and George was part of the movement. Shortly before he arrived at Dartmouth, alumni had won half the seats on the Board of Trustees. Then, on a bitter cold winter morning during George's junior year, Dartmouth Hall burned down. The College's last link with the early days of Wheelock and Indian education, the Hall was an emotional touchstone for Dartmouth graduates. An unprecedented fundraising drive resulted in a rebuilt Hall.

While George and his Bedbug Alley friends were scattered to dorms and rooming houses around campus, President Tucker called a general meeting of alumni from around the nation. The young secretary of the College, Ernest Martin Hopkins '01, worked to form Dartmouth's first nationwide alumni organization, the Class Secretaries Association. For many years, George was to serve the class of 1905 as its secretary, and in 1969 at the age of 86, just months before his death he was chosen Class Secretary of the Year.

The links with Dartmouth continued posthumously. Among his Greek students at Montclair was his son William F. Putnam '30, who followed in his father's footsteps by majoring in Greek at Dartmouth before becoming a doctor. And a grandson, George Putnam Butterworth '72, also became a doctor.

From farm boy to Greek scholar and sire to a line of professionals, George Putnam had come a long way. But so had turn-of-the-century Dartmouth.

For $100, farmer's son became a college man.

Between Jols, Meorge wrete hir folks.

The college, minue the old fine.

"Once a strictlyprovincial school,Dartmouth hadacquired a reputationin the big cities."

Writer Constance E . Putnam lives in Concord, Massachusetts.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryThe Rise of Research

February 1989 By Anne Bagamery '78 -

Feature

FeatureA Story of Drama, Fierce Competition, Mom and Apple Pie

February 1989 By George Canizares -

Article

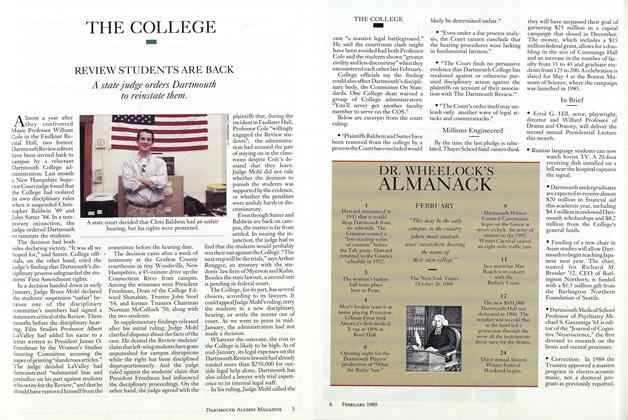

ArticleREVIEW STUDENTS ARE BACK

February 1989 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1988

February 1989 By Chuck Young -

Article

ArticleThe Battle Against AIDS

February 1989 By Martha Hennessey '76 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

February 1989 By Peter Frechette

Features

-

Feature

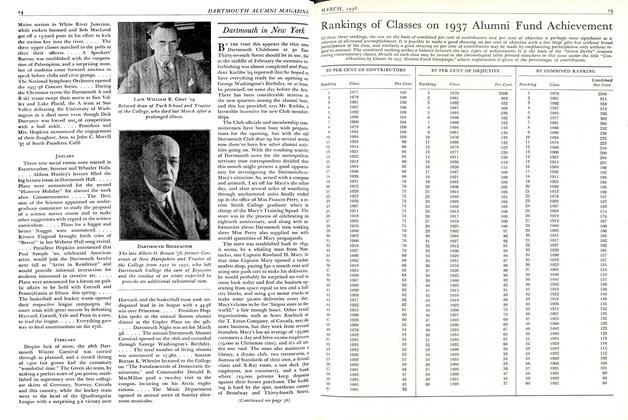

FeatureRankings of Classes on 1937 Alumni Fund Achievement

March 1938 -

Features

FeaturesMixed

MAY | JUNE 2014 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryCAN WE TALK?

MAY 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

July/August 2006 By JOHN SHERMAN -

Feature

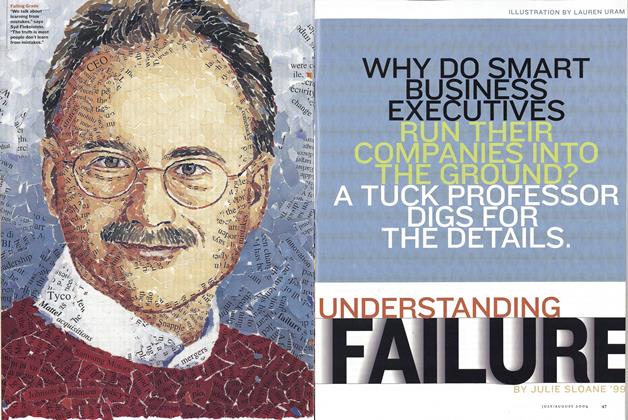

FeatureUnderstanding Failure

Jul/Aug 2004 By JULIE SLOANE ’99 -

Feature

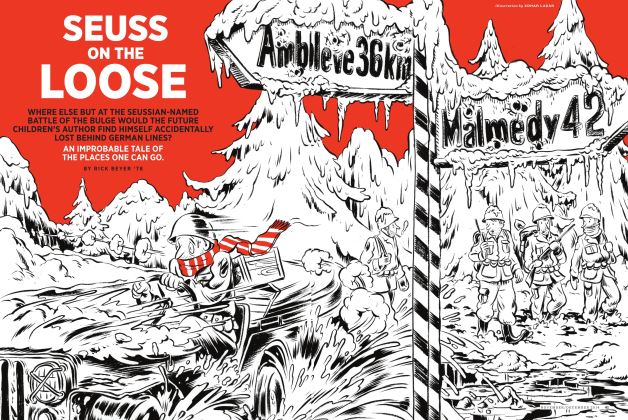

FeatureSeuss On the Loose

NovembeR | decembeR By RICK BEYER ’78