Faculty members insist on being scholars as well as teachers; what does this mean for the students?

It's a familiar scene, played a thousand times at alumni interviews and college nights around the country at about this time of year. "Harvard, Berkeley, Michigan yes, those are all very good schools," says the Dartmouth representative to the high school senior, in best damning with-faint-praise manner. "But their emphasis is on research, not on undergraduates. They're, well, universities. Dartmouth" pause for effect "Dartmouth is a college."

the institution as a "college" at all. It's a good line but, like most sales pitches, it's only partially true. Thanks to Daniel Webster, Dartmouth will probably be called a college for years to come. But in many ways it is now a university. With three professional schools, thriving graduate programs in the sciences, improved facilities and an increased emphasis on research, Dartmouth has evolved to the point where many on campus have stopped referring to

Still, the recruiters aren't entirely off the mark. If Dartmouth is a university, it is a small one. A recent study of graduate programs at Dartmouth shows that its faculty members produce fewer research publications, supervise fewer graduate students, and have fewer colleagues in their departments than those of most research universities. But Dartmouth is not exactly a college, either. Similar comparisons with schools such as Williams and Middlebury show that Dartmouth conducts much more research and grants many more higher degrees than does its elite small college competition. Concludes P. Bruce Pipes,a physics professor and dean of graduate studies: "The question is no longer whether Dartmouth is a college or a university, but what kind of university Dartmouth is going to be."

As it happens, President James O. Freedman helped answer that question in a major speech to the faculty in October and, at the same time, set the tone for yet another debate about Dartmouth's future. (Thespeech was reprinted in the winterissue.) Proclaiming that Dartmouth was already a "liberal arts university," Freedman laid out his goals: to slough off the small-college image, promote a stronger emphasis on research and scholarship by faculty and students, and rethink Dartmouth'sgraduate programs. As if to ward off visions of a new Gal Tech on the Connecticut, Freedman hastened to add that Dartmouth would "not become a traditional, large-scale, highly impersonal research university," nor would it diminish its commitment to undergraduate education; rather, he said, Dartmouth will draw on "the best of what we are" by integrating the two.

What Freedman is proposing is one of the more delicate balancing acts in higher education. The chasm between high-powered research and undergraduate teaching is an established part of the academic landscape. Few schools have even tried to breach it. Stanford, Princeton and Duke have come close, but they fall short of the symbiotic relationship that Freedman seems to be striving for.

Can Dartmouth pull it off? As might be expected, there is much debate on campus over whether the president's vision is possible or even desirable. Success as a liberal arts university would depend on two critical areas: fundraising and the faculty. For Dartmouth cannot be a contender in higher powered university research without competing more successfully for research funding and it cannot ensure a high-quality undergraduate experience without faculty who are willing to integrate students into what Freedman calls "the creation of new knowledge."

Fortunately, Dartmouth seems to have a head start in both areas. In the past five years the College has attracted a wealth of funding from corporations and foundations moneys that usually go not to endowment or facilities, but straight into specific projects. In fiscal year 1987-88, fully 25 percent of Dartmouth's externally generated funds came from corporations and foundations. By way of comparison, Harvard and Princeton receive around 40 percent of their external funding from corporate and foundation sources; atM.I.T. the figure is closer to 60 percent. Freedman has called for raising more research funds and relying less on endowments, tuition and alumni giving.

Dartmouth also has managed to attract, by a combination of hard recruiting and institutional support, faculty members who are committed to scholarship. As a consequence, grants for faculty research have also climbed: in fiscal 1988 Dartmouth faculty received 424 awards for a total of $38 million, the largest amount ever received by the College.

Ken Spritz is involved with both the fundraising and faculty aspects of Dartmouth's "universitization." As head of corporate and foundation support for the past four years, Spritz has helped bring about the sizeable increase in corporate and foundation funds for research, including major grants from Pfizer Pharmaceuticals, New England Digital Corporation, and the Pew Memorial Trust. He also keeps close tabs on faculty research, looking for projects that might open the door with companies. "With corporate America there's always a quid pro quo," he says, leaning back in his chair in his Blunt Alumni Center office overlooking Baker Library. "You have to be able to talk specific projects, not just glad-hand over campus issues."

Spritz thinks that in order for Dartmouth to sustain itself as even a small university, it will have to do a better job of fundraising on the university model that is, competing for "mega-grants" from major donors. "The needs of this institution just to maintain leadership in areas in which we're currently involved are staggering," he says, ticking them off on his fingers. "Look at the library: $50 to $60 million in capital needs. The Fairchild Physical Sciences Building: nothing extravagant, just an upgrade to existing labs and a small expansion which is badly needed $25 million.

"And that's not even looking at the question of, What if we expanded facilities for research and added some graduate programs?" he continues. "Where would we put the people? Where would we build the labs? Trailers and quonset huts don't quite fit into the Dartmouth environment. Any expansion has got to take that into account."

Traditionally, says Spritz, Dartmouth has gone after corporate funds the way it has sought reunion gifts: with personal appeals by alumni volunteers. While this method has had some success, Spritz thinks that increased competition for corporate funds and the College's rising capital needs will dictate a more strategic approach—based less on old school ties and more on enlightened self interest. "Corporations want two things from academic America our graduates and access to our research," he says. "If they're getting that in fair numbers and with some regularity, it makes it much easier to go in and talk to them about our institutional needs in a way they really can't ignore." As a small institution, on the other hand, Dartmouth has trouble delivering the numbers.

So how can the College compete for funding with the likes of M.I.T. and Berkeley? By emphasizing its areas of unique strength, Spritz replies. Some of these areas Kiewit Computation Center, the Thayer School's Ice Research Laboratory and the Rassias Foundation (for language training) have already proven to be successful draws for corporate funds. "If M.I.T. is a department store," says Spritz, "then Dartmouth is a boutique fewer items, but very high quality."

One of those responsible for keeping the shelves stocked is Nathan Dinces, director of industrially sponsored research. Whereas Spritz tries to promote interest in Dartmouth's broader institutional needs, Dinces is after corporate sponsorship of specific research projects, usually ones that may produce a patentable product or process. He also sees it as part of his job to help raise Dartmouth's profile as a research institution, on campus and off. "At Stanford, big-shot researchers are folk, heroes," he says. "At Dartmouth, most students don't even know important research is going on. Where are they supposed to learn about it in Time magazine?"

Three and one-half years ago, Dinces' job didn't exist. Its creation reflects the increase in industrial monies available for research nationwide and the seriousness with which the College has decided to pursue them. At Dartmouth the numbers are still relatively small, but growing: in fiscal 1988 it received more than $38 million in total external sponsorship for research, a 20 percent increase from 1987. Princeton, by contrast, received $65 million last year for its Plasma Physics Lab alone.

Like Spritz, Dinces thinks Dartmouth can and should be competing harder for industrial funds. But he realizes that his position is controversial because of the perception that sponsored research comes with strings attached, and therefore is academically impure. "I'm not talking about heavy-duty contract work, or 'Star Wars,' " he asserts. "But there are legitimate areas of academic inquiry that may also be of interest to industry, and that is entirely appropriate to Dartmouth's liberal arts mission." Dinces thinks that as Dartmouth gets used to the idea of being a university, its attitudes toward research will become more sophisticated.

Actually, the College has been heading in that direction for some time albeit in fits and starts be ginning with the presidency of Ernest Fox Nichols (1909-1916), a world renowned physicist whose plans for expansion were stymied by the outbreak of World War I. Nichols' successor, Ernest Martin Hopkins '01, had a different vision of higher education and for 30 years deliberately played down research in favor of the small-college model.

It was John Sloan Dickey '29 who ushered in the modern era of research and teaching at Dartmouth. Dickey, who became president in 1945, felt that a faculty oriented toward the "production of ideas" was essential to the College's competitiveness, as well as the nation's. Among the faculty he recruited was a young mathematician and former research assistant to Albert Einstein named John G. Kemeny, who continued to attract research-oriented teaching faculty after he succeeded Dickey in 1970. Kemeny himself was a model of the teaching scholar. Throughout his presidency he taught one course per year, usually to upperclassmen, as well as keeping up his research activities. Teaching, he used to say, was as important as scholarship because it kept the mind sharp.

The model of .the Dartmouth faculty member who balances a fall teaching load with research and scholarship endures to this day. But it has become harder to live up to. In the Arts and Sciences, year-round operation has placed new demands on faculty, who now endure intense ten week terms and must supervise an increased number of off-campus study programs in all disciplines. At the same time, there has been a generational shift at universities nationwide toward faculty members whose primary career focus is research. Although those who come to Dartmouth are aware of the College's emphasis on undergraduate teaching, "part of their heart lies in the library or in the lab," says Jim Poage, vice provost for computing. "They do research not because they have to but because they want to."

This new generation is not wholly satisfied with Dartmouth's commitment to research. A survey of the faculty conducted last year found that only 55.1 percent felt that the College " provides sufficient support for scholarly development." According to the campus committee that conducted the survey as part of a study of Dartmouth's intellectual environment, this growing passion for research is creating divisions within the academic community. "The faculty, in effect, have adopted the research university as the appropriate model for themselves and their students," the committee reported. "The students, not surprisingly, have not adopted that model." The committee warned that this faculty attitude "will isolate them from the students unless the students themselves move toward a greater interest in research."

Involving undergraduates in research is a cornerstone of the liberal arts university unveiled in Freedman's October speech. His earlier statements about wanting more academically oriented students, a broader curriculum and a higherpowered faculty are also pieces of the same picture. Not coincidentally, Freedman's speech followed closely on the release of three self-study reports by on campus committees as part of Dartmouth's ten-year accreditation with the New England Association of Schools and Colleges. The committee that studied the College's intellectual environment recommended that Dartmouth do more to get undergraduates involved in academic research.

To some extent this is already happening. Physics Professor John Walsh, one of the most active researchers on the faculty, accepts two or three undergraduates each year as lab assistants. The students, usually honors physics majors recruited as juniors, work alongside Walsh and his staff of research assistants and graduate students. By spending two years as part of the same project team, the undergraduates have "one year to learn, and one year to do some really good work," says Walsh.

Undergraduate research, and research in general at Dartmouth, may be greatly aided by two projects designed to help faculty and students in their scholarship. One is Project NORTHSTAR, a cooperative venture with IBM and Sun Microsystems to develop a powerful computer workstation for science and engineering students. The other is the Dartmouth College Information System, a software package that would allow users of the 6,000 Apple Macintosh computers and other work stations on campus to tie into any of 2.0 databases with visual images as well as facts.

Jim Poage says that many of the major research universities would like to set up systems similar to DCIS. But whereas they estimate their startup costs at $8 million to $10 million, Poage thinks he can get DCIS off the ground for as little as $3 million because Dartmouth already has the network and workstations. "Doing research in the backwoods of New Hampshire can be a serious problem if you don't have access to information," says Poage. "This is one area where Dartmouth can use its strength to overcome certain inherent disadvantages." He hopes to have DCIS up and running within five years.

As more faculty draw undergraduates into their work, many on campus think Dartmouth might also see improvement in one of its strongest selling points: faculty student relations. As Associate Dean Gregory Prince puts it: "Faculty members don't want to go to cocktail parties or pot-luck suppers; they want to spend time doing the things they're interested in." Undergraduates alone cannot always provide a professor with sufficient research support, however, and future debate over Dartmouth as a university will entail graduate students. Should the num- ber of programs be expanded? Should they exist in their own right or, true to Dartmouth tradition, primarily support undergraduate programs? "We've got to have more graduate programs to maintain the quality of teaching," argues Trustee Ira Michael Heyman '51, chancellor of the University of California at Berkeley. But not everyone is convinced that Dartmouth needs more graduate programs in order to be a good university, or even a good college. The main issue is quality control: unless Dartmouth can attract top-notch graduate students a difficult job for new programs some faculty members think that the quality of undergraduate education will suffer because of the drain on faculty members' time.

"Bad graduate students just get you confirmed in bad ways," says Professor Bernard Gert, whose department, philosophy, voted against a Ph.D. program six years ago. "Graduate students are one way of keeping fresh, but they're by no means the only way."

A majority of faculty agree that any expansion should be done with caution. A survey by the accreditation committee that studied graduate programs found that professors favored strengthening existing ones before launching new ventures. Faculty in departments that do not have such programs said that new ones would be enormously expensive. These same faculty members felt that the creation of new programs outside the natural sciences, where graduate research is currently centered, "might weaken the quality of undergraduate programs and heighten research versus teaching tensions."

There is another reason for proceeding carefully: once a school starts a graduate program it has made a commitment that cannot be easily broken. "If you got the heads of all the major research universities together for a beer," says Jim Poage, "they would probably confide that they'd like to shed 50 percent of their graduate programs because they're substandard and unproductive." Dartmouth has a considerable advantage, he maintains, in being able to pick and choose which programs it offers "to do it right, or not do it at all."

The new master's program in electronic music, which was approved last year, is an example of the way Dartmouth may approach any farther expansion of graduate studies. According to Music Professor Jon Appleton, the program which will admit only six students was debated for a year and only passed because it fulfilled four requirements: it capitalizes on a unique strength (the new Bregman Electronic Music Studio); it offers a degree that no other school will offer; it teaches skills that are in demand; and, finally, it will, benefit undergraduates by extending the curriculum open to them. "The general feeling among the faculty," says Appleton, "was that these are the minimum acceptable criteria."

A traditional objection to graduate programs is the fear that grad students might begin teaching classes, setting a dangerous precedent against Dartmouth's reputation as a school where professors teach the courses. But that precedent has already been established. Graduate students frequently give lectures and serve as lab instructors. In the Math Department, some teach entire courses. Both faculty and students seem to feel that their presence does more good than harm. Eighty-two percent of faculty in departments with graduate programs say that they have a "positive impact" on undergraduate education. A similar survey of undergraduates found that grad students got fairly high marks as teachers. "The age gap with grad students is so much smaller than with faculty members," explains Nathan Dinces, himself a former graduate student in molecular biology. "An undergraduate can say, 'Here's this person who wears the same jeans, drinks the same beer, feels the same pain as I do but that person is reading a fifteenth-century philosopher I never heard of, and enjoys it.'

The committee on graduate programs concluded that grad studies should receive a larger share of the university pie, and that they deserve more "administrative attention." But both the committee and President Freedman have not yet urged an increase in the actual number of programs.

Freedman did say, however, that to fulfill Dartmouth's "destiny" as a liberal arts university requires an increase in the size of the faculty itself. As college budgeters know only too well, this is the most expensive kind of expansion a school can undertake. It is perhaps this ambition that has provoked the greatest skepticism on campus. "President Freedman has evoked a grand picture for which he entirely lacks the resources," said Ted Fletcher, a member of the Graduate Student Council, to the daily Dartmouth. "It's a nice pipe dream but the reality of the vision is a long way off."

Even some members of the faculty wonder whether the increased emphasis on research won't harm teaching. Edward Bradley, chairman of the Classics Department, told the student paper: "I think that Dartmouth should strive for greater excellence in the area of undergraduate education and not dissipate its resources in an attempt to become a pale imitation of Yale or Harvard."

And yet, expenses aside, the concept of Dartmouth as a liberal arts university isn't really as apocalyptic as it appears. By placing a greater emphasis on research, and keeping the overall scope small, most faculty seem to think that Dartmouth is taking the surest course to growth and enhancement of its existing strengths including undergraduate education. "There is no question but that Dartmouth is a university, and has been for some time," says Dan Lynch, associate dean of the Thayer School. "But it also continues to be true that Dartmouth is a small college, and yet there are those who love

Latin American scholar Diana Taylor sees terrorism as the "ultimate theater of cruelty."

"Dartmouth conductsmuch more researchthan does its elitesmall-collegecompetition."

"The model of thefaculty member whobalances a fullteaching load withresearch andscholarship endures.But it has becomeharder to live up to."

"Not everyone isconvinced thatDartmouth needsmore graduateprograms in order tobe a good university,or even a goodcollege."

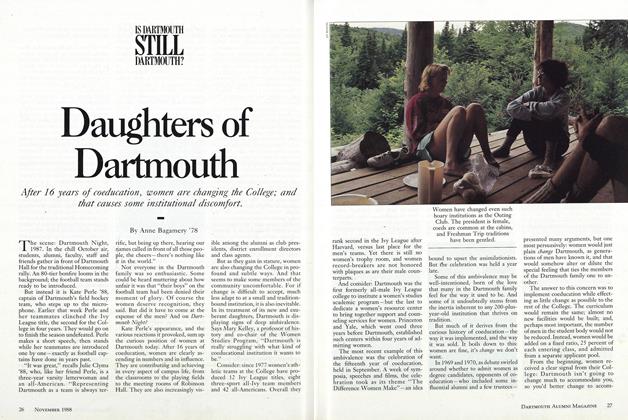

A former Forbes magazine staffer, Anne. Bagamery '78 is a writer living in London. Her article "Daughters of Dartmouth" appeared in the November issue

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureGeorge's College

February 1989 By Constance E. Putnam -

Feature

FeatureA Story of Drama, Fierce Competition, Mom and Apple Pie

February 1989 By George Canizares -

Article

ArticleREVIEW STUDENTS ARE BACK

February 1989 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1988

February 1989 By Chuck Young -

Article

ArticleThe Battle Against AIDS

February 1989 By Martha Hennessey '76 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1982

February 1989 By Peter Frechette