The scene took place a decade and a half ago, one of those classroom epiphanies in which you learn as much about the professor as about the subject. Robert Pack—Dartmouth graduate class of 1951, renowned poet, and English professor at Middlebury College—was talking about one of his profession's chief concerns: to knit together the disorder of the universe. And Mr. Pack, a writer who reveled in what he called "the willed happiness of art," had just had a bad day.

"I was filled with a kind of cosmic dread," he told his Modern American Poetry class in a raspy Bronx accent. "Contemplation of the meaninglessness of the infinitesimal blink of time we live in had gotten to me.

"I was on an errand to the grocery store, driving down the street like a modern-day Job, asking some higher authority for a sign of order. And then," he said, looking up toward the classroom ceiling, "there literally came a sign: over the grocery store, in big block cosmic letters, were the words 'Grand Union.' And I was filled with a happiness that I hadn't felt in days." He paused, and his students turned to each other with respectful looks that thinly disguised what they all were feeling: this guy was nuts.

But he was also one of the most respected teachers on campus, director of the Bread Loaf Writer's Conference, prolific publisher of poetry, children's books, critical works, a translation of Mozart's librettos, and a volume on the correspondence of John Keats. Who were the students to say he was crazy, this man who had devoted his life's work to the task of "naming and glorifying...what is lovable" on this earth? From his hilltop home in Cornwall, Vermont, Bob Pack celebrated what he called "the pleasure the senses may take in a fertile and generative world. These experiences are the utmost," he said, "and they are possible."

A decade and a half later, a former student finds that the teacher-poet has changed little. He still lives on the hill He has now published a total of 26 books. His title has gotten longer to include an endowed chair. And his poetry has become more ambitious, or at least covers more territory. The earth is a bit too confined for his soaring metaphors; his latest book straddles the origin of the universe and the minutiae of particle physics (which, as the physicist and the poet both know, are one and the same thing). The man can still find his Grand Union in a grocery store. He sees the laws of molecular movement in his cat, the Uncertainty Principle of electrons in his wife, and the origin of everything in his garden. Amid a decaying universe, in the wake of a heart bypass operation that struck him with his own mortality, he orders his own domestic heaven. In one of his most recent poems, he writes:

Come with me now to tend thegarden;yes, my rakish son, come hoe alongwith me;and we'll compose from dusta round of ordered entropy.

"I try," he explains, "to treat the cosmos as if it were the state of Vermont. " You can see the effort in his most recently published work, a booklength cycle of poems inspired by the writings of physicist Heinz R. Pagels. In firmly crafted verse, Pack takes the wild disorder of the universe and tames it, condensing whole galaxies into a fish, for instance:

I watchedthe sizzling rainbow trout that night,its smeared red stripe surrou?ided byblack dotscollapsed suns lost in their trapped light.

Pack's sun is a "household star," a cow, a bee, a girl named Dolores. The world is a "legendary eggplant." The Big Bang theory of the universe's origins is a raunchy joke, a soup cook, and a giant bout of cosmic flatulence. The book has poems on quarks and quasars, neutrinos and proton decay, on the Doppler effect and on Einstein—who sits in heaven wearing a T-shirt that reads "E=mc2." Pack still says things like, "Colors are the gratuitous cosmic pleasure. I mean, everything could have been black and white."

The former student who hears this can't help but recall the teacher in the classroom, his compact body leaning forward as he read his willfully cheerful poetry, and think: "Maybe he really is crazy."

On the other hand, in poetic terms he may be something of a hero. This is a man who faces terrifying issues when he goes to the grocery store; what demons does he battle when he sits alone in his hilltop house? "All the world is an aberration in the face of entropic movement," he says, pointing out the belief of physicists that the universe is flying a part at an awe- some rate. "My poems resist entropy in a formal sense; they're highly structured, with the randomness of the lines' meters held within firm bounds.

"I hope not to flinch in the face of a vast process," he continues, speaking again of the universe and its terrible ways. "An easy consolation would be religious belief. But I think that's a form of evasion. The trick is not to flinch and still to be able to love the universe of infinite change, infinite loss." Pack says a crucial literary forebear of his book is the Book of Job, "who must suspend his ethical longings and simply contemplate the mag- nificence that God creates." The reward for such biblical meekness, Pack told his students years ago, "is the happiness that comes from the acceptance of limits."

His celebration of what Robert Frost called "a small good thing," of the world compacted into upland Vermont, led the poet Donald Justice, in a 1985 New York Times book review, to call Pack "the true heir" of Frost.

In poetry, perhaps, but Pack sees himself also as a teacher—a more devoted one than that other Vermonter. "I remember sitting at Frost's feet at Dartmouth," he says. "But Frost didn't have a teacher's stick-to-itive- ness. Teaching is more like being married than having a romance, and Frost was a romancer."

It was at Dartmouth where Pack began courting poetry himself. His first great love was science—an early ambition was to be a veterinarian. He was more into sports than poetry in his Bronx, New York, high school. He captained the baseball team, was a star halfback, swam competitively, and lifted weights. He also sang in the school chorus and reportedly dated one of the most attractive girls. But at Dartmouth he began to contemplate the universe within him, becoming one of those many well-rounded Dartmouth students over the ages who saw themselves as closet creative loners. After graduating he did an abortive stint at an ad agency, got a Fullbright to Italy, earned a master's at Columbia, served as poetry editor of a literary magazine, taught at Barnard and married one of his students, wrote voluminously, and, in 1964, went to Middlebury.

He expects to be there the rest of his life, and he expects his life to be satisfyingly long, heart surgery and all. "Although I've gotten a little grouchier over the years, less patient with the uninvolved students, my pleasure in teaching has remained undiminished," he says. "I want to be the first professor at Middlebury to continue teaching after 100."

To anyone concerned that our cosmos is flying apart, it is an attractive picture, the centenarian Dartmouth graduate teaching dumbfounded students. There is this poet in the future, an ordered spot in the universe, making a happy struggle against his own entropy. M

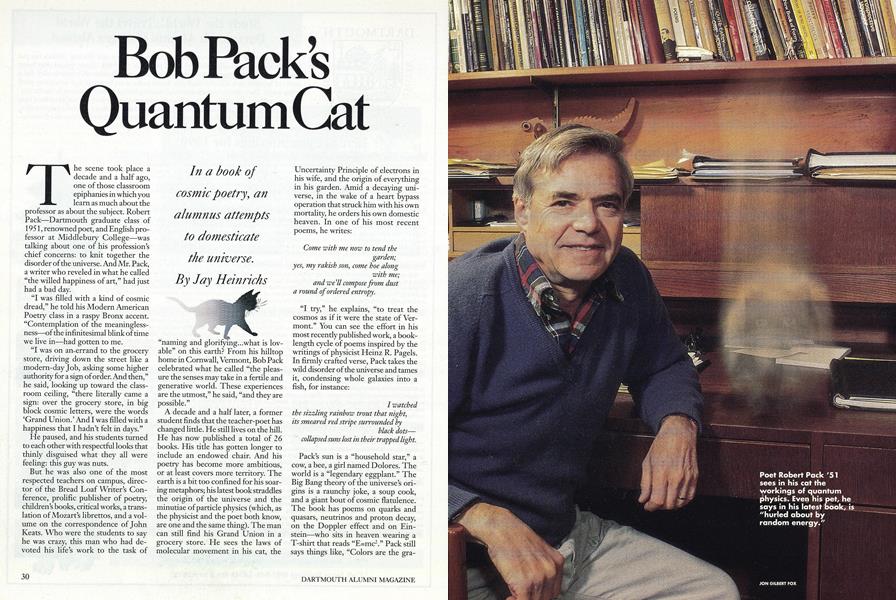

Poet Robert Pack '51 sees in his cat the workings of quantum physics. Even his pet, he says in his latest book, is "hurled about by random energy."

In a book ofcosmic poetry, analumnus attemptsto domesticatethe universe.

"Teaching is more likebeing married than having a romance,and Frost was a romancer "

Jay Heinrichs, who is editor of this magazine, studied poetry with Robert Packduring the seventies.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

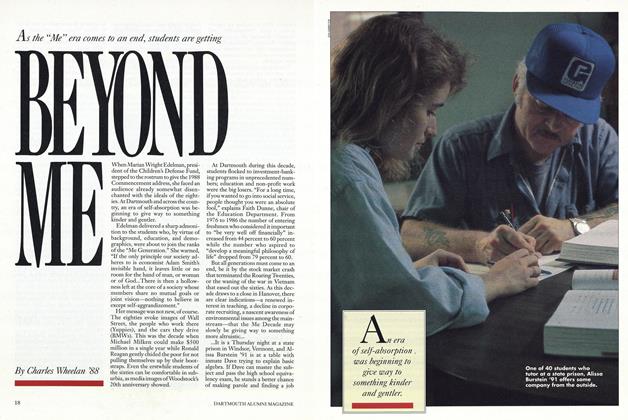

Cover StoryBEYOND ME

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

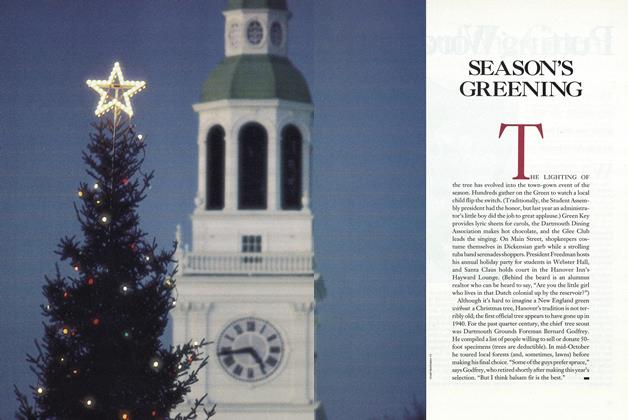

FeatureSEASON'S GREENING

December 1989 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

December 1989 -

Sports

SportsThe College's First Fan Picks a Winner

December 1989 By Noel Perrin -

Class Notes

Class Notes1958

December 1989 By Fred Louis 111

Jay Heinrichs

-

Article

ArticleHanover Scene

MARCH • 1987 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleOut of the Woods

NOVEMBER 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleNineties-Version Clubs Have a Heart

NOVEMBER 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleA Poet in The Cosmos

NOVEMBER 1993 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleNels Comes Home

April 1995 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

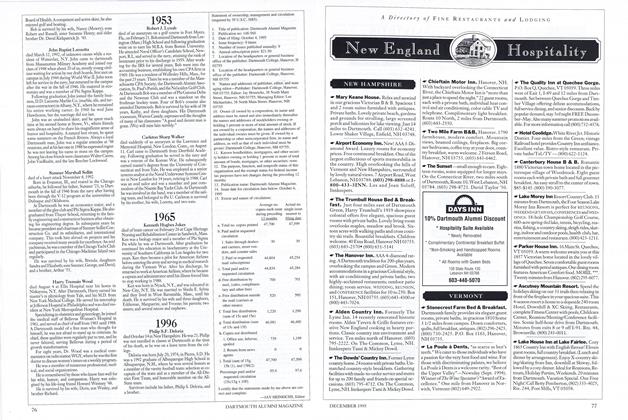

ArticleStatement of Ownership, Management and Circulation (required by 39 U.S.C. 3685).

December 1995 By JAY HEINRICHS