Once a mere introduction to the outdoor life, freshman trips now have a new component: the life of the mind.

As you read this, the first of a record 885 students are beginning to hike, bike, canoe, fish, rock climb, or examine the countryside between Vermont and Maine. More than 85 percent of the class of 1993 are taking part in more than 100 freshman trips. Students run the whole thing, using contributions by alumni classes to buy equipment to loan to those who can't afford it. Organizers say one reason for greater participation is a new option: four new "intellectual" trips, in which freshmen stay in DOC cabins and study art, literature, and the environment. Unlike two years ago, there are no urban trips, and the DOC has chosen not to follow last year's suggestion by a faculty committee that trips be led to Boston museums.

But the new trips do respond to criticism by some faculty members that the outdoor experience is an inadequate introduction to Dartmouth. Not all faculty are critical, mind you; some 15 have signed up to lead trips this year. But the talk hit the DOC leaders hard.

The critics said that carrying packs up mountains and singing school songs around campfires hardly foster President Freedman's image of the creative loner. If Dartmouth is going to be a truly intellectual place, they said, the wilderness shouldn't be the first thing students see, and school songs shouldn't be the first thing they learn.

To an outsider, it might seem strange that anyone in an academic institution would question the role of intellectualism. Nearly everyone salutes the life of the mind at Dartmouth, but the community has yet to agree on where that life belongs or even what it is, exactly. The issue goes back to President Hopkins, who said the College's function "is not primarily to develop intellectualism but intelligent men." Until recently, few people at the College felt it necessary to portray the outdoor life as an intellectual experience; the effects that Hopkins and his successors described had to do more with the spirit than the mind. The traditional voice that hollered in the wilderness was a robust one, crying out of a yawp just barbaric enough to be admirable.

But students are an adaptable species. "We were hurt by the criticism of freshman trips," says Carrie Kull '89, head of the DOC's 19-year-old Environmental Studies Division. "But it's necessary that traditions' purposes be challenged constantly. Otherwise they have force without direction."

If the College wants the outdoor experience to have an intellectual component, the students said, so be it. Environmental study provides one good means. Public interest in the planet is already on the rise at Dartmouth. A course on "Earth as an Ecosystem" had 137 students last year—more than a hundred above the previous year's number. Enrollment in a course on environmental health almost doubled. And the College's recycling program, which was started by students, is being imitated by universities across the nation.

The quest for intellectualism goes beyond outdoor programs, though. Since President Freedman came two years ago he has emphasized liberal arts' role in increasing undergraduates' "capacity to create new knowledge" which requires a teaching faculty that is engaged in research. Just where the institution should fall in the frontier between research and teaching is controversial, of course. But with the assumption that the College desires both elements, investment banker Jerome Goldstein '54 has established an annual $1,500 award for "Outstanding Achievement in Creative or Scholarly Work." In 1978, the Goldstein family funded a prize for distinguished undergraduate teaching.

While a number of alumni have criticized the emphasis on research, some on campus don't think the College is willing to go far enough. One of them is Biology Professor Edward Berger, who on January 1 will leave his post as department chairman to go to the University of Maryland. In an interview with The Dartmouth, Berger cited a "lack of funding and interest" in a planned molecular genetics institute as a prime reason for his move.

Research-and-teaching will almost certainly be on the mind of History Professor James Wright, who is beginning a four-year term as Dartmouth's new dean of faculty. But minority recruitment and faculty salaries will likely require more day-today decisions. Wright replaces Math Professor Dwight Lahr, who resigned in March to resume full-time teaching and research. Lahr was an ardent advocate of hiring minority faculty; one of his last moves as dean was a controversial "Minority First" proposal to consider race before specialty in hiring qualified professors. Although Wright hasn't said what he thinks of the proposal, he says he supports "aggressive" affirmative action.

An even tougher problem for Wright is the faculty pay scale. The average salary for Arts and Sciences faculty is $48,052 up from $38,126 in l985 but it remains the lowest in the Ivy League. Dartmouth's endowment is small compared to other Ivy schools', and salary hikes must come out of a strapped budget that relies heavily on tuition. The era of twodigit tuition increases appears to have ended, which brings us to the problem faced by Wright and the College budgeters: will faculty pay remain in the Ivy cellar? If not, where will the money come from?

Nota Bene

• Here's one for the College-University debate. The Council for Advancement and Support of Education has awarded the Dartmouth Alumni Magazine two silver medals for general excellence in a college publication and for last September's cover story on admissions. As an experiment, we also entered the university-magazine competition. The judges never got back to us.

• During the turmoil in China last spring, the Dartmouth community moved quickly to support its 100 Chinese members. The College provided a crisis center in Parkhurst and $2,000 for telephoning, while a local office-machine firm loaned a fax. On June 9, the Executive Committee of the Faculty passed a resolution condemning repression by the Chinese government. And undergraduates presented New Hampshire Congressman Chuck Douglas with a petition supporting legislation to allow Chinese students to remain in the States.

• It has been ten years since John Steel '54 became Dartmouth's only successful ful challenger in a Trustee election. His maximum two terms will end next June, and the Alumni Council will nominate a successor in November. The Council's nominating committee says it welcomes suggestions for candidates. The deadline is October 15. Send names and bios to committee chairman W.G. Barker Jr. '54, CBS Fox, 1211 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10036,

• Cable television's ESPN will feature Dartmouth in two Ivy Games of the Week during football season. It will broadcast the opening home game against Princeton on September 16. And it will show the homecoming game against Yale on October 14.

• Dartmouth's Hood Museum was called a "national model" for other college and regional museums in a report released during the summer by the American Association of Museums. Written by a visiting accreditation committee, the report praises the Hood for quality "perhaps unequalled in college or university museums." This should please the new director, James Cuno, who recently arrived on campus. Cuno, who was head of UCLA's graphic-arts center, is an expert on the painter Jasper Johns.

• Readers may notice a few changes in the magazine's format. This column is the biggest one. We've asked our two Whitney Campbell Interns to begin keeping weekly diaries of their lives on campus, and we're alert for the kinds of stories that portray the College as it is. Readers have asked us to show what it is like to be a student here today. We hope this monthly journal helps.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

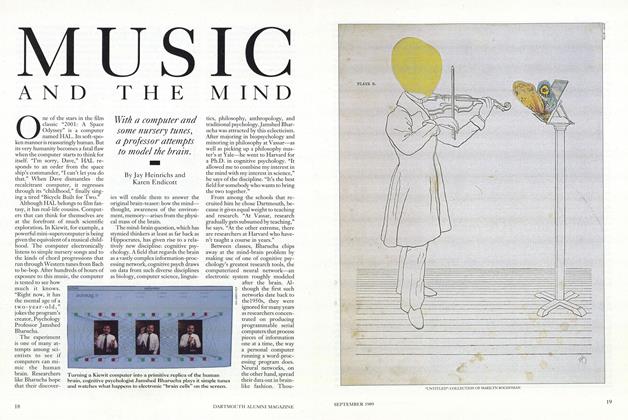

Cover StoryMUSIC AND THE MIND

September 1989 By Jay Heinrichs and Karen Endicott -

Feature

FeatureA Cure for Nostalgia: the Ultimate Comp Exam

September 1989 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

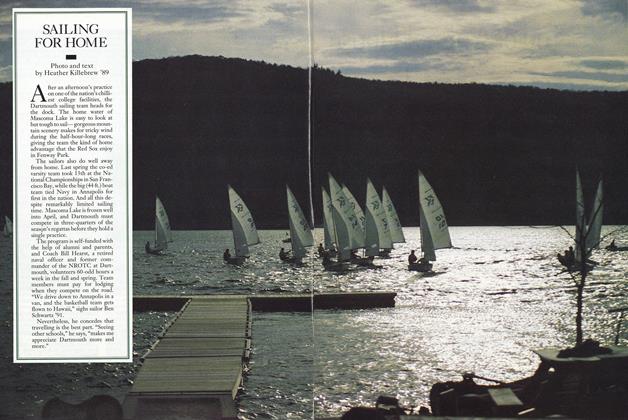

FeatureSAILING FOR HOME

September 1989 By Heather Killebrew '89 -

Feature

FeatureSon of Animal House

September 1989 By Ed. -

Article

ArticleThe man who wrote the movie returns to find brothers in slime.

September 1989 By Chris Miller '63 -

Sports

SportsDartmouth's Quarterback Says No to the Baseball Draft

September 1989