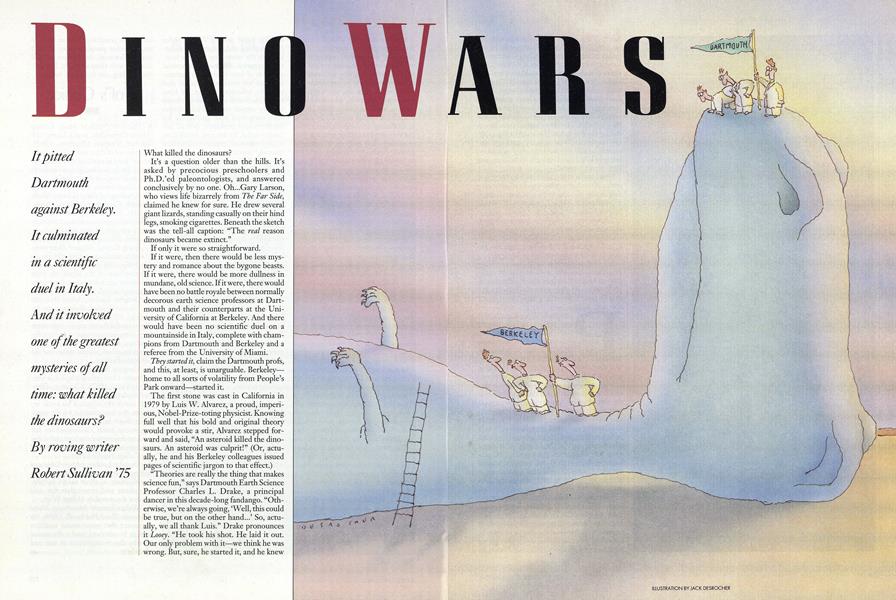

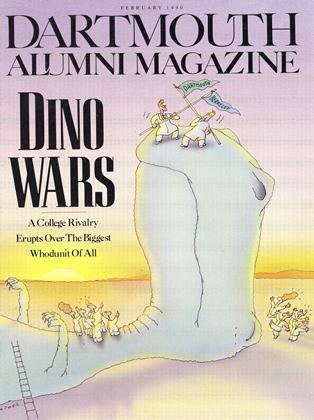

It pittedDartmouthagainst Berkeley.It culminatedin a scientificduel in Italy.And it involvedone of the greatestmysteries of alltime: what killedthe dinosaurs?

What killed the dinosaurs?

It's a question older than the hills. It's asked by precocious preschoolers and Ph.D.'ed paleontologists, and answered conclusively by no one. Oh...Gary Larson, who views life bizarrely from The Far Side, claimed he knew for sure. He drew several giant lizards, standing casually on their hind legs, smoking cigarettes. Beneath the sketch was the tell-all caption: "The real reason dinosaurs became extinct."

If only it were so straightforward.

If it were, then there would be less mystery and romance about the bygone beasts. If it were, there would be more dullness in mundane, old science. If it were, there would have been no battle royale between normally decorous earth science professors at Dartmouth and their counterparts at the University of California at Berkeley. And there would have been no scientific duel on a mountainside in Italy, complete with champions from Dartmouth and Berkeley and a referee from the University of Miami.

They started it, claim the Dartmouth profs, and this, at least, is unarguable. Berkeley― home to all sorts of volatility from People's Park onward—started it.

The first stone was cast in California in 1979 by Luis W. Alvarez, a proud, imperious, Nobel-Prize-toting physicist. Knowing fall well that his bold and original theory would provoke a stir, Alvarez stepped for ward and said, "An asteroid killed the dinosaurs. An asteroid was culprit!" (Or, actually, he and his Berkeley colleagues issued pages of scientific jargon to that effect.)

"Theories are really the thing that makes science fun," says Dartmouth Earth Science Professor Charles L. Drake, a principal dancer in this decade-long fandango. "Otherwise, we're always going, 'Well, this could be true, but on the other hand...' So, actually, we all thank Luis." Drake pronounces it Looey. "He took his shot. He laid it out. Our only problem with it—we think he was wrong. But, sure, he started it, and he knew that it would grab attention."

But not even the late Dr. Alvarez, an attention seeker of high repute, could have guessed at the enormity of the debate he was inciting. His pronouncement touched off a firestorm of reaction. To deal in suitably cataclysmic if hopelessly mixed metaphors, the squabble grew dinosaurian in its dimension, volcanic in its implications. Whatkilled the dinosaurs? leaped out of scientific journals and onto the editorial pages of The New York Times—twice! Itmade its way to National Geographic and to Larson's FarSide drawing board. It achieved American pop culture's quintessential anointment, the cover of Time magazine. The artwork featured a beleaguered dinosaur bellowing in fear as a rain of comets pelted the earth; the issue flew off newsstands everywhere. Kids were talking about dino demise in school, and their parents were discussing it over cocktails. The debate lured scientists from around the world and from several disciplines. According to some, it hampered academic careers.

Curiously, it boiled down to an intercollegiate squabble, a scientific version of the Army-Navy game. "Yes, somehow it has become Berkeley versus Dartmouth, fourth quarter, the clock running," says Dartmouth Research Professor Charles B. Officer. "We never guessed that this would happen."

"No, we didn't," Drake agrees. "But, actually, when you think about it—we probably could have guessed, or at least guessed at how big it would be. First, every kid is interested in dinosaurs. They wouldn't be kids if they weren't. The dinosaur part was essential for the PR value. If you said a big asteroid hit the earth 66 million years ago, everyone would say ho-hum. If you said an asteroid killed the dinosaurs 66 million years ago, then whammo!

"And there was Luis himself. He was a contentious type who was used to being deferred to when he made a pronouncement. If challenged, then I'm afraid he would behave badly. And he did.

"When you think about it in retrospect, the uproar becomes less surprising. It involved dinosaurs, outer space, and mystery. It had everything going for it but rape, incest, and the royal family."

A review of the dino wars indicates that this is accurate—the royals stayed above the fray, and there is no hint of sexual impropriety between or among the participants. But there's nearly everything else.

Prior to 1980, this much only was agreed upon: dinosaurs had lived for 150 million years, starting at a point more than 210 million years ago. That kind of longevity proves that they were quite well adapted to life on earth. Consider that we humans walked out of Mesopotamia a mere 12,000 years ago—one seventeen-thousand-five-hundredth of the dino dynasty. Anyways...dinosaurs prospered for a long time and then, between 65 and 66 million years ago, just at the end of the Cretaceous Period, they died out. It happened either quickly—say, over 100 years, which is a snap of the fingers in geologic time. Or it happened more gradually, perhaps between 10,000 and several hundred thousand years. (These time frames represent an important battleground in the dino wars.)

What killed them? Maybe just a heavy dose of Darwinism, as some fitter species survived when the big guys could not. Perhaps the climatic changes wrought by shifting oceans finished off the dinosaurs. Maybe the heavy volcanic action that was ongoing near the end of the Cretaceous Period so affected the earth's air and water that the largest living organisms could no longer thrive. Or maybe they smoked too many cigarettes.

In 1979 Alvarez announced that the key had been found during a dig in a cliff near Gubbio, in central Italy's Umbrian Apennine Mountains. He, along with his son Walter—a geophysicist who today succeeds his late father as chief crusader for the comet theory—and others in the "Berkeley group" discovered a high count of the element iridium in a layer of clay that dated to the approximate time of the dinosaurs' demise. Since metallic iridium is more abundant in meteorites than in rock from the earth's crust, the scientists assumed an impact from an extraterrestrial sphere some 65 or 66 million years ago. Luis stretched his hypothesis, and put it in laymen's terms: a massive asteroid or comet, perhaps six miles in diameter, rammed the earth at the end of the Cretaceous Period. The impact set off immense forest fires and threw up a mushroom cloud of sediment. The haze of smoke and dust blanketed the earth, blocking sunlight for an unspecified but protracted period. This would not only have caused a plummet in the earth's temperature but would have affected photosynthesis in plants. The plants would have died during this "asteroidal winter." The animals that depended upon the plants would have died. The dinosaurs would have died.

The time zone at the end of the Cretaceous Period and beginning of the Tertiary—known scientifically as the "K/T boundary"—was truly an epochal one in the history of our planet. Fossils show that there were mass extinctions not only of dinosaurs but of other animals and plants during this time. The Alvarez theory fit neatly with this foreknowledge; it provided a suitably cata clysmic event that would explain the high death toll. It was neat. Moreover, with its dinos and comets, it had a certain sexiness. It was appealing, alluring, seductive. You wanted to believe it. Consider that when it was challenged within the scientific community, a saddened New York Times head lined its editorial on the dispute, "Did Dinosaurs Die a Dull Death?" Like, what could possibly be worse?

Scientists set off immediately to farther investigate Alvarez's theory, and there seemed to be some early substantiation. There were findings of high iridium counts at the same geologic level elsewhere in the world. (Proving the asteroid cloud dispersed and settled uniformly?) Soot, too, was found in K/T boundary clay. (From the cometcuased wildfires?) Shocked quartz was also discovered. (An extraterrestrial impact pulverized this earth mineral?)

But from the very first, there were dissenters. One question presented itself quickly. Where's the crater, huh, for this six-mile-wide comet? Where's the 90-mile crater it would create as it smashed into the planet? Ummmmmm, well, ahhhh...Under the sea! Yeah, that's the ticket! Hiding underthe sea!

Other, less easily evaded challenges followed. A primary one involved the long held belief of fossil-studying paleontologists that the many species of dinosaur did not vanish in a geologic instant (100 years or less) but died out slowly—one by one—in response to more gradual changes that were taking place during the close of the Cretaceous Period. (This is the "Dull Death" scenario.) Some scientists, while not disputing that a comet may have landed and may have thrown some iridium, maintained that the fossil record showed most dinosaurs were already extinct or nearly extinct by the time of this theoretical big bang. They said the extinctions, which may have taken as long as a half-million years, were perhaps due to massive volcanos, altered climate, changing sea levels, and perhaps a few Darwin-satisflyiing diseases.

In 1979 Dewey M. McLean, a geologist at Virginia Polytechnic, had published a paper in the journal Science incorporating several of these ideas. He had suggested that there were elevated levels of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere near the end of the Cretaceous Period, and that the resulting global warming—not dissimilar to today's hypothe sized "greenhouse effect"—harmed and maybe killed some animals. Once the Alvarez theory was on the table, McLean took his own ideas further. He suggested that the C02 had been released from within the earth by the Deccan Traps, a phenomenal and long-lasting volcanic burst—the planet's largest in the last 200 million years—that occurred on the Indian subcontinent in advance of K/T boundary time. McLean said that the volcano (or volcanos) could also be responsible for Alvarez's elevated iridium, since this element exists in greater quantity beneath the earth's crust than it does on the surface. The Deccan Traps had burped up the iridium, he implied. Other researchers have subsequently suggested that an explosion as mammoth as the Deccan Traps, which obviously would have involved intense heat, could also have shocked that quartz.

Enter Dartmouth.

"I remember that in the early eighties Luis had given a talk at the National Academy of Sciences in Washington," says Chuck Drake as he sits peacefully on the back porch of his Norwich home. The sun is out, the view of the valley is magnificent, and Drake speaks with a tone of calm and bemusement. "I was at the academy shortly afterwards, and the guys there were saying that Luis's talk had been about the comet theory, and their attitude was, 'Well, Luis proved that. Let's go on to other things.' But I had a fair amount of skepticism.

"There was this conference in Snowbird, Utah, in October of '81. It was set up to discuss Luis's theory, and I got invited. Subsequently, I wrote a little report about the meeting, expressing skepticism." Drake felt that with the seas receding, air changing, and India erupting all at once at the K/T boundary, a comet strike was too simple a solution. He was particularly bothered by the small time frame implied by a dust-cloud extinction theory. He figured the Deccan Traps, which resulted in at least a million cubic kilometers of lava being spewed during a period of as much as 500,000 years, seemed a more probable dino-killer than a comet.

He found an ally in Officer. Drake had known and liked Officer since their grad-school days at Columbia. They had arrived at Dartmouth more or less together in the late sixties, and they had collaborated on other research prior to 1980. The two Chucks were and are a bright, companionable team.

Upon his return to Hanover, Drake told Officer of the proceedings in Snowbird. He told him of his qualms. "I agreed with Chuck immediately," says Officer as he sits behind the desk in his East South Street office. (He runs a marine-environment consultancy as a sideline to his duties at the College.) Officer re-lights his pipe and continues. "If things happened as Luis hypothesized—that the dinosaurs all went out on June sixteenth, 65 million years ago, or something like that-then there ought to be one big bone collection somewhere, all from the same time. And there just isn't anything like that out there."

On March 25, 1983, Officer and Drake published a report in Science concluding that fossil sequences and other deposition evidence from the K/T boundary "put into question the interpretation that an extrater restrial event was the cause of the faunal changes and the iridium anomaly in the vicinity of the Cretaceous-Tertiary transition. It seems more likely that an explanation for the changes during the transition will come from continued* examination of the great variety of terrestrial events that took place at that time, including intense volcanism, major regression of the sea from the land, geochemical changes, and paleo climatic changes." Two years later they followed up with another Science report finding "that iridium and other associated elements were not deposited instantaneously but during a time interval spanning some 10,000 to 100,000 years. The available geologic evidence favors a mantle rather than meteoric origin for these elements. These results are in accord with the scenario of a series of intense eruptive volcanic events during a relatively short geologic time interval and not with the scenario of a single large asteroid impact event."

Officer, puffing away, pushes some charts of fossil studies from Tunisia and Texas across the desk. He starts pointing at signs of extinction. "Look," he says, "a bunch went out there at that time, a bunch there, a bunch there. That couldn't be due to an instantaneous event." He sits back and sighs. "I was naive, okay? I didn't realize what we were getting into, okay? I didn't realize people's egos and reputations would be put on the line. I thought it would be a straightforward scientific inquiry." Drake says he had a feeling it might devolve into something less high-minded. "You knew if you were gonna screw around with Luis, he wasn't going to take it lying down."

Luis Alvarez, unleashing the fury of a scientist scorned, ridiculed the Dartmouth duo and a third earth sciences colleague of theirs, Robert Jastrow. Alvarez insisted "there isn't any debate. There's not a single member of the National Academy of Sciences" who shared the Dartmouth view. But what of the scores of scientists who, at a 1985 gathering of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontologists, said in an informal poll that the comet theory was ill-founded? "I don't like to say bad things about paleontologists," Alvarez claimed somewhat disingenuously in an interview with Malcolm W. Browne of The New York Times, "but they're really not very good scientists. They're more like stamp collectors." Harrumph!

Things got even uglier. Several unnamed scientists told Browne that the Alvarez camp had tried—unsuccessfully—to intervene with officials at Virginia Polytechnic to block Dewey McLean's promotion to fall professor. They said there had been attempts to discredit McLean's work. Other scientists sympathetic with Dartmouth accused the Berkeley group of trying to exclude them from scientific meetings and publications, particularly Science.

Alvarez denied the charge regarding McLean, and the editors of Science denied that they exhibited any bias in rejecting submissions. But Alvarez then launched into some very public name-calling. He belittled Jastrow, an astronomer, as "not a very good scientist" because of Jastrow's support of the Star Wars defense plan. In retaliation Jastrow pointed out that Alvarez, who had played a role in the development of the atom bomb, was among only five physicists willing to denounce their old boss, Robert Oppenheimer, before the Atomic Energy Commission in 1954.

Gentlemen. Gentlemen!

"It's regrettable, no question," says Drake. "Chuck always took it more seriously than I did—all that name-calling and recrimination. I sort of chuckled at it. But it did have a serious downside. Once we at Dartmouth had somehow picked up the cudgel on the other side, it became an us-against-them thing and both sides were forced into harder positions, conceding nothing. That's unfortunate. That's not the best science." Officer and Drake, joined at various times by Britain's Anthony Hallam, Canada's James H. Crocket and other scientists, continued to present evidence that the iridium levels in Italy occurred at not just one geologic point in time but at several. They also suggested that the Deccan Traps explosions might have caused global acid rain, chemical changes in the seas, and depletion of the atmosphere's ozone layer which would have allowed the sun's ultraviolet radiation to impact upon living organisms.

Greenhouse effect, acid rain, ozone depletion: suddenly the debate, which obviously needed no extra baggage, took on political overtones. Carl Sagan, between appearances on Johnny Carson, had drawn up his mid-eighties "nuclear winter" scenario based on Alvarez's "asteroidal winter" model. Now others, whose various agendas concerned everything from acidic deposition to greenhouse gases, searched for implications in the Dartmouth theory. If a buildup of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere killed the dinosaurs, or if a hole in the ozone finished them off, what does that mean for us? For our CO2-spewing cars? For our chlorofluoro- carbon-chomping refrigerators? Are we buying our own extinction with this manmade Deccan Traps known as the twentieth century?

The stakes, like the invective, seemed to be getting higher and higher. Then in 1988 Luis W. Alvarez, unquestionably the seminal figure in the debate, died. The great man was no longer on the attack, and could no longer be attacked.

Late in 1988, Walter Alvarez called Chuck Drake to see if they could resolve one crucial point in the debate. In a report in Geology published earlier in the year, Drake, Officer, and Crocket had said that their 1987 excavations at the Gubbio site had yielded high iridium levels both two meters above and two meters below the K/T boundary level. That is: high iridium concentrations had been deposited over a period of some 300,000 years. "To account for the iridium distribution near the K/T boundary, intense volcanic activity is a preferred alternative to impact of extraterrestrial material," they concluded.

Walter Alvarez was proposing a return to square one. He wanted to go back to Gubbio along with a member of the Dartmouth group and an impartial referee. The team representatives would collect rock samples from all around the K/T boundary, then the referee would disseminate the uncoded samples among analysts within the scientific community. The reports of these researchers would at last and at least tell us whether the iridium was deposited over 100 years or over a considerably longer period of time.

Fine, said Drake, and he agreed to Alvarez's nomination for referee, Robert N. Ginsburg of the University of Miami.

In mid-September of 1989 Alvarez and Gary D. Johnson, yet another Dartmouth earth sciences prof recruited by the Chuck and Chuck Dino Squad, chopped away at the Umbrian cliffs as Ginsburg looked on. "It went fantastically well," reports Johnson.

"We were able to agree that some sites that had been used in the past weren't good, and should be eliminated for research purposes. Then we were able to get good new samples, I think, from the sites we agreed upon." Right now, the minerals that they collected are in the hands of analysts at several laboratories. This spring Ginsburg will announce the results. Finally, we'll know what killed the dinosaurs.

...Or will we? Walter Alvarez has long maintained that it could have been a whole slew of comets that were responsible, not just the one big one that his father envisioned. This, of course, would stretch out the timeline for extraterrestrial iridium being brought to earth. "We'll learn some things in the spring," says Drake. "We may know if that iridium in Italy was deposited during K/T boundary time, or over a long period. But some things we'll never know. I'm convinced of that. I think we might never have an elegant agreement on what killed the dinosaurs." He pauses, smiles. "That's okay. Mysteries are fun."

Robert Sullivan '75 is a write?-for Sports Illustratedwho frequently covers science and natural-resources topics. He visited the earth sciencesprofessors at Dartmouth in September. To hedgehis extinction bets (Gary Larson could be right,after all), Sullivan doesn't smoke.

Berkeley's Alvarezesstarted the uproar withtheir asteroid theory.

Volcanoes are theculprits, say theCollege's Dino Squad.

Some said there was anattempt to block DeweyMcLean's promotion.

"The squabblegrewdinosaurianin itsdimension,volcanic in itsimplications."

"Finally,we'll knowwhat killed thedinosaurs...orwill we?"

"If a hole inthe ozonefinished thedinosaurs offwhat does thatmean for us?"

"It boileddown to ascientificversion ofthe Army-NavyGame."

"It involveddinosaurs,outer space,and mystery.It hadeverythinggoing for itbut rape,incest; and theroyalfamily."

"WalterAlvarezwanted to goback to Gubbioalong with amember of theDartmouthgroup and animpartialreferee."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

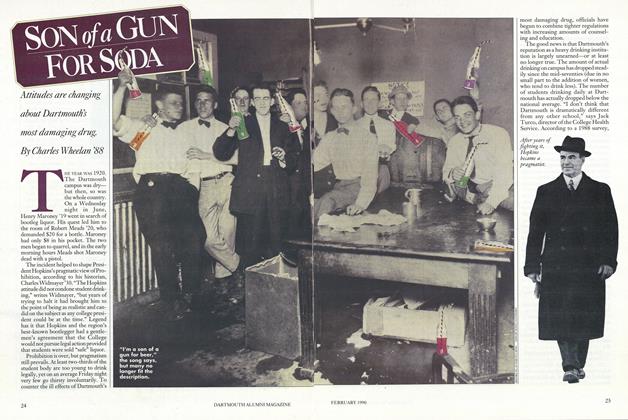

FeatureSon of a Gun for soda

February 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureIf You Thought the Comps Were Hard, Try This Quiz

February 1990 By Nancy Staab '90 -

Feature

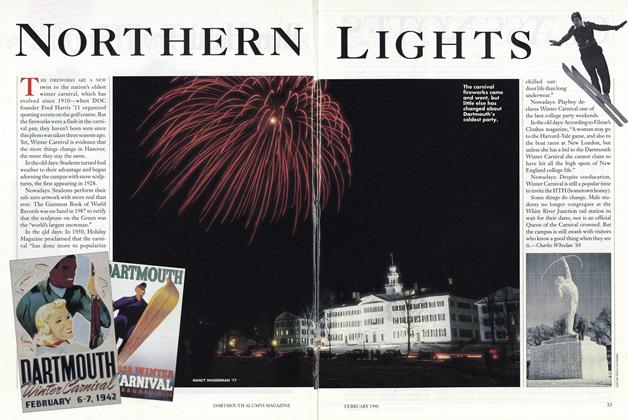

FeatureNorthern Lights

February 1990 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

February 1990 -

Article

ArticleTHE ETHICS OF THE BOMB

February 1990 By Professor Walter Sinnott-Armstrong -

Class Notes

Class Notes1975

February 1990 By W. Blake Winchell