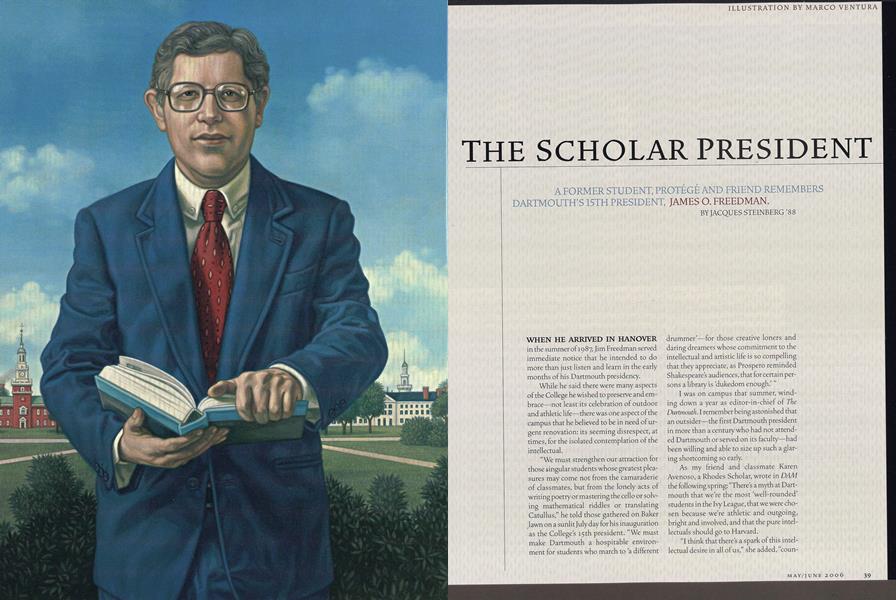

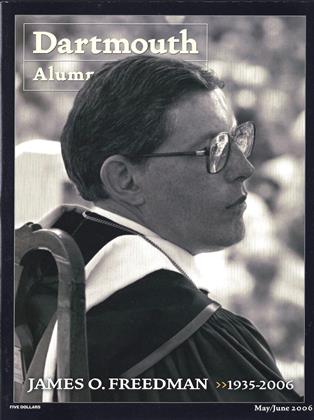

The Scholar President

A former student, protege and friend remembers Dartmouth’s 15th president, James O. Freedman.

May/June 2006 JACQUES STEINBERG ’88A former student, protege and friend remembers Dartmouth’s 15th president, James O. Freedman.

May/June 2006 JACQUES STEINBERG ’88A FORMER STUDENT, PROTEGE AND FRIEND REMEMBERS DARTMOUTH'S 15TH PRESIDENT. JAMES O. FREEDMAN.

WHEN HE ARRIVED IN HANOVER

in the summer of 1987, Jim Freedman served immediate notice that he intended to do more than just listen and learn in the early months of his Dartmouth presidency.

While he said there were many aspects of the College he wished to preserve and embrace—not least its celebration of outdoor and athletic was one aspect of the campus that he believed to be in need of urgent renovation: its seeming disrespect, at times, for the isolated contemplation of the intellectual.

"We must strengthen our attraction for those singular students whose greatest pleasures may come not from the camaraderie of classmates, but from the lonely acts of writing poetry or mastering the cello or solving mathematical riddles or translating Catullus," he told those gathered on Baker lawn on a sunlit July day for his inauguration as the Colleges 15th president. "We must make Dartmouth a hospitable environment for students who march to 'a different drummer'—for those creative loners and daring dreamers whose commitment to the intellectual and artistic life is so compelling that they appreciate, as Prospero reminded Shakespeare's audiences, that for certain persons a library is 'dukedom enough.'"

I was on campus that summer, winding down a year as editor-in-chief of TheDartmouth. I remember being astonished that an outsider—the first Dartmouth president in more than a century who had not attended Dartmouth or served on its faculty—had been willing and able to size up such a glaring shortcoming so early.

As my friend and classmate Karen Avenoso, a Rhodes Scholar, wrote in DAM the following spring: "There's a myth at Dartmouth that we're the most 'well-rounded students in the Ivy League, that we were chosen because we're athletic and outgoing, bright and involved, and that the pure intellectuals should go to Harvard.

"I think that there's a spark of this intellectual desire in all of us," she added, "counterbalanced by the fear of revealing it to our friends." Somehow, Freedman had managed to forge an immediate connection with Avenoso and others who had experienced similar frustrations— before we had even gotten to know him.

I, for one, was left with an immediate follow-up question: Did this man, who had come on so serious so early, also have a sense of humor?

My answer would come soon enough.

When a classmate asked me that fall to record the outgoing greeting on her answering machine, I quickly accepted the assignment and decided to channel my inner James O. Freedman.

"Sarah Jackson isn't here right now, she's out writing poetry or translating Catullus," I began, trying to replicate Freedman's voice, which was as smooth as maple syrup yet crackled with remnants of a boyhood spent downstate in Manchester, New Hampshire. "But if you leave a message at the sound of the cello, she'll get back to you."

It never occurred to either of us that our new president might actually hear that message. But as it turned out, Jackson had requested an interview with Freedman, in her capacity as executive editor of The D. And when his office called Jackson's room to confirm the appointment, his secretary was left so speechless that she redialed the number so Freedman could hear the message for himself.

Jackson was immediately summoned to Parkhurst, and an inquiry was convened. When pressed by the new president, she admirably refused to identify the voice on her machine. But when a second friend, a class officer, was pressed by Freedman, she gave me up in a heartbeat.

When my turn came, Freedman greeted me with a broad grin and assured me that this was a president who could laugh at himself.

Though I had spoken to him once before for The D—by phone while he was in lowa, four days after he had accepted the Dartmouth presidency—this was probably the first time I had seen him face to face, in that glorious office just steps from the Green. The last time would be under far different circumstances, in a hospital room on the 12 th floor of Massachusetts General Hospital, nearly two decades later and just 22 days before his death, on March 21, after a long battle with non-Hodgkin's lymphoma. He was 70.

In those intervening years Freedman went from being an official I covered to a mentor and a friend, one who would teach me, both by his words and by example, the value of living a life filled with passionate curiosity. It was a hunger that he sought to sate on a daily basis through his exhaustive reading across a range of media (the classics and The New York Review of Books, of course, as well as TheBoston Globe sports page and a journalism blog) and also in spirited conversations, phone calls, letters and e-mails. He could, it seemed, talk about anything, from the merits of a recent biography of Eudora Welty to the chances that Curt Schilling would have a good season pitching for his beloved Red Sox this year.

In what would be the final weeks of his life, he kept close tabs on the unraveling of the tenure of another college president—Larry Summers of Harvard, where Freedman graduated in 1957—as well as the triumphs and setbacks of the Bush administration.

"He didn't want to miss anything," his friend Howard Gardner, the noted Harvard psychologist, reflected on the day after Freedman's death. "He loved life. He wanted to be there. When he couldn't be there, present himself," Gardner added, in reference to the toll Freedman's illness ultimately took on his mobility and, sadly, his ability to read, "we were his eyes and ears."

In what was perhaps his last public comment—outside of a memoir of the first three decades of his life, which is due to be published by Princeton University Press in the spring of 2007— Freedman had a letter published in The New York Times on January 18. In it he lamented the recently concluded Supreme Court confirmation hearings of Justice Samuel Alito: "Two suggestions for diminishing the tedium of Senate hearings on federal judicial nominations: Reduce the size of the Senate Judiciary Committee from 18 to 10 members; and locate the initial round(s) of questioning (before the senators take over) in a professional moderator not likely to be given to long patches of self-aggrandizing oratory.

"Jim Lehrer would be an excellent choice," added Freedman, who once worked in journalism as a copy boy and reporter at the UnionLeader in Manchester as well as in the federal judiciary as a law clerk to a future Supreme Court justice, Thurgood Marshall, on the U.S. Court of Appeals.

Freedman had come to Dartmouth from the University of lowa, where he had been president the previous five years. Before that he had been dean of the law school at the University of Pennsylvania, and before that a law professor at Penn. He may have been born in New Hampshire, but he had the challenge of replacing the ultimate Dartmouth insider. David McLaughlin '54, his predecessor, had raised enormous amounts of money from the alumni (many of whom remembered his exploits as a star Dartmouth football player) and had built the Rockefeller Center, among other buildings, but had lost the confidence of a faculty that would have preferred a president with a Ph.D.

Freedman had an LL.B., which he earned at Yale Law School in 1962. But would all this talk of intellectualism scare away the alumni and students in the bargain? It didn't take long for the ominous predictions to begin: Donations were sure to fall, some lamented, as this man who did not seem to understand our traditions, let alone seem able to find his way to Memorial Field on a fall Saturday for a football game, took the helm.

Certainly no one could have foreseen what would happen in the capital campaign that ended in November 1996, on Freedmans watch. It was the most successful in the Colleges history and netted $568.2 million, exceeding the campaigns original goal by $143 million. (He also became a regular presence at home football games.)

While proud of that fundraising accomplishment and the building boom it helped touch off, I suspect Freedman would not have wanted that to be the signal measure of his 11-year presidency.

Making good on his inaugural address, Freedman engineered the first overhaul of the Dartmouth curriculum in 70 years, expanding student requirements from courses in three broad disciplines (the humanities, social sciences and physical sciences) to eight (including the arts, social analysis and philosophical, religious or historical analysis). Seniors would also be required to engage in a "culminating or integrating experience" in their majors.

Mindful of the loner he evoked in that first speech, he established the presidential scholars program, which gave 60 juniors and seniors each year the opportunity to work alongside professors and researchers on individual projects. On the admissions front, he helped boost the SAT scores of incoming students and, beginning in the fall of 1995 with the class of 1999, achieved parity between men and women (who, in his first year in office, had made up only 38 percent of the student body).

uniform, he responded forcefully, upholding the paper's right to publish but deploring its tactics and point of view.

"Acts of such appalling bigotry have no place at this college," said Freedman, who was Jewish, in an address at a rally on the Green.

Similarly, when he was asked to speak at the dedication of the Roth Center for Jewish Life in November 1997, he decided to publicly share his research into one of the darkest periods of Dartmouth's historyand that of other institutions of higher learning, including Harvard and Yale. The subject of his talk: the anti-Semitic quotas that had been intended to cap the percentage of Jewish students in the early decades of the 20 th century.

Among the documents he had drawn from the Dartmouth archives was an exchange of letters between an alumnus and the director of admissions, Robert C. Strong '24, in the summer of 1934.

As recounted in a November 1997 NewYork Times article, Freedman quoted the alumnus, Ford C. Whelden '25, as complaining that '"the campus seems more Jewish each time I arrive in Hanover. And unfortunately many of them (on quick judgment) seem to be the 'kike' type." As Freedman told it, Strong replied: "I am glad to have your comments on the Jewish problem, and I shall appreciate your help along this line in the future. If we go beyond the 5 percent or 6 percent in the class of 1938, I shall be grieved beyond words."

Freedman displayed courage in the way he conducted his personal life as well. Two years before Lance Armstrong won his first Tour de France as a recovering cancer patient, Freedman began his own public battle with cancer, one that would last a decade. When his thick black-and-gray hair, always combed so closely, fell out during his early treatments, Freedman made no effort to hide a scalp that was, temporarily, nearly bald. He even displayed it at Commencement in 1994.

But it was what he said that really resonated. He had, he told the graduates of the class of 1994, drawn sustenance during his illness from the words of the great writers he had been reading all his life, those whose works were among the thousands of volumes in a personal collection that protected Freedman like a fortress. Suddenly, it was clear that the loner he had described in his opening address seven years earlier, the one who delighted in burying his nose in a book, was Jim Freedman.

"Hearing a physician say the word cancer' has an uncanny ability to concentrate the mind," he told the graduating class. "That is what liberal education does, too. God willing, this disease and my liberal education will each, in its own way, prove to me a blessing."

A moment later, he added: "When the ground seems to shake and shift beneath us, liberal education provides perspective, enabling us to see life steadily and see it whole. It has taken an illness to remind me, in my middle age, of that lesson. But that is just another way of saying that life, like liberal education, continues to speak to us—if we have the courage and stillness to listen."

These were themes that Freedman would address in several books, including Idealism and Liberal Education (University of Michigan Press, 1996) and Liberal Educationand the Public Interest (University of lowa Press, 2003). His forthcoming memoir traverses similar territory, but in a far more personal way. It describes a love of reading forged in boyhood, an upbringing in which he said he sometimes felt painfully shy and lonely, and ends on the day he met his wife, Bathsheba, a clinical psychologist, at age 27. In addition to Sheba, Freedman is survived by his son Jared, daughter Debbie and four grandchildren.

I was always amazed at the many, varied lives Freedman touched, not just during his tenure at Dartmouth but after he and Sheba retired to Cambridge in the late 19905. What was also striking was how no two of those friendships were rooted in quite the same soil.

Writer David Halberstam was one friend. Though Halberstam had been a senior at Harvard when Freedman was a freshman, they had not known each other. "He was terribly shy," Halberstam said of Freedmans Harvard days in a conversation the day after Freedman died. "He regretted not going out for The Crimson. But Jim lived a life in books. He wasn't athletic or popular in high school, when these things are so important. Even at Harvard he felt shy."

The two met about 15 years ago, when, in an essay for the Harvard Alumni Bulletin about the pleasures of reading, Freedman mentioned Halberstams epic indictment of the architects of the Vietnam War, The Bestand the Brightest. After reading the reference in the bulletin, Halberstam wrote to Freedman, and a friendship was quickly born.

"We were brought together by an affection for baseball, an admiration of the Red Sox teams of the 19405, but above all a love of books," Halberstam said. "He had this towering humanity. I think of him as a truly Talmudic figure. His modesty. His love of letters. His belief in an ethical life. His faith in American democracy. He was a great big democrat, with a lower case'd.'"

When, on October 25, 2004, Halberstam had an extra ticket for Game Two of the World Series at Fenway Park, he asked Freedman, a lifelong Red Sox fan who (like Sheba) rarely missed a televised game. At that time Freedman was somewhat immobilized by yet another recurrence of his cancer, but to Halberstam's amazement, he rallied and went to the game. And this was no ordinary game—this was one of the games in which Schilling pitched on a balky ankle with blood seeping through his sock.

Recalling Freedman's enthusiasm that night, Halberstam said, "He was like a little boy."

Harvard professor Gardner is, by his own admission, not much interested in baseball or other sports. But like Halberstam, he and Freedman shared "connective tissue," as Gardner described it, knitted across countless books and essays. They seemed to read so many of the same books and articles in a given year that Gardner would sometimes make lists of titles so as not to forget the works he wanted the two to discuss.

They had met on a so-called Renaissance Weekend—those gatherings of thinkers, business people and politicians, most notably Bill Clinton—in the mid 1990s. But they got to know each other in earnest shortly thereafter, when they became hopelessly lost on a car ride to a friends house for dinner.

Afterward, Gardner received a note from Freedman. It said: "I'm glad we got lost. We had time to get to know one another. I could see we were destined to become friends."

Freedman and I always connected across a shared love of journalism and journalists. When, in my senior year at Dartmouth, I told Freedman that I was applying to be a clerk for Scotty Reston, the longtime columnist for The New York Times, Freedman agreed to write my recommendation. For all that he had accomplished in his life by that time, he was thrilled to be writing a letter that he knew Reston, whom he had long admired, would be reading.

I sensed then that Freedman—who, as his many speeches as president demonstrate, was a writer of uncommonly clear, vivid prose—was a frustrated reporter in an academic's robes. The day after he died, Gardner told me, "I think he would have been every bit as happy, or happier, as a journalist. Where he would have gotten in trouble was his mother was fiercely ambitious for him."

After I became a reporter at The Times, Freedman was forever plying me for goodnatured Times gossip. What were Maureen Dowd and Linda Greenhouse really like, he would ask. How was the paper recovering from the scandals perpetrated on it by Jay son Blair, Howell Raines and Judith Miller? In one of our last visits he peppered me with questions about why I had structured a recent article in a particular way he said, respectfully, that he would have counseled another approach—and why in God's name had a copyeditor chosen the particular headline that appeared over that story?

"What I wouldn't give to be a fly on the wall of your newsroom for just a day," he once told me.

On a Sunday night in January of 1993 I came as close as I could to fulfilling that wish, when I enlisted Freedman as the most overqualified "leg man" that I have ever retained in my nearly 17-year career as a reporter at The Times. On that night I was working the night-rewrite shift when the death of Thurgood Marshall was announced. An obituary had already been prepared in advance, but from a standing start, and with just a few hours to go before the presses would roll, I was assigned to assemble the recollections of some of Marshall's former clerks.

And so I called Freedman,who was living in the presidents mansion at Dartmouth. Luckily, he was home.

When I told him of my assignment, he quickly went to his Rolodex to retrieve the names and numbers of several of the justices former clerks on the Supreme Court. I then took a few minutes to interview Freedman for his perspective on Marshall's earlier career as a civil rights lawyer and judge on the federal bench.

Freedman said that Marshall's crowning achievement was surely his victory in Brown v. Board of Education, the 1954 case in which the Supreme Court declared that "separate but equal" public schools for blacks and whites no longer had a place in America. "He is probably the only person ever to have been appointed to the Supreme Court who would have had a place in American history before his appointment," Freedman said, before I hustled him off the phone so I could make other calls.

The next morning I called Freedman at his office in Parkhurst to thank him for his help with the article, which appeared alongside the jump of the Marshall obituary. Then I asked him if he would take a moment to turn to page A 2, so I might get his response to the "Quotation of the Day."

From 200 miles away I could hear the papers on his desk rustle, followed by a long pause. Then I heard that unmistakable voice again, the one I remembered so clearly from my senior fall, exclaim, "Oh my God!"

The quote was what Freedman had told me about Marshall. It was the first time a quote in one of my articles had been elevated to The Times' equivalent of the winner s circle, and, for that matter, the first time an utterance of Freedman's had been deemed so worthy

In our last visit together in that hospital room in Boston, as his body was failing him but his mind remained laser sharp, Freedman and I reminisced about that shared journalistic milestone, such as it was.

And, just as we had that day in Parkhurst after he caught me doing that imitation of his Catullus speech, we laughed.

Freedman was the first Dartmouth president since 1822 to have no previous ties to the institution, but he quickly found his way. Above, Freedman and his wife, Bathsheba, dine with freshmen at Moosilauke Ravine Lodge in 1990. Calling Freedman a lover of books would be putting it mildly—his collection exceeded 6,000 volumes. At left, he examines some titles at the Dartmouth Bookstore in 1989. When did he find time to read? "At night a little, on airplanes a lot," he said.

Freedman dons his inauguration robe, July 19,1987.

FREEDMAN ESTABLISHED THE PRESIDENTIAL SCHOLARS PROGRAM, HELPED BOOST SAT SCORES OF INCOMING STUDENTS AND RELISHED SUMMONING HIS COURAGE TO PLAY THE ROLE OF TRUTH-TELLER.

JACQUES STEINBERG covers the media for The New York Times.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

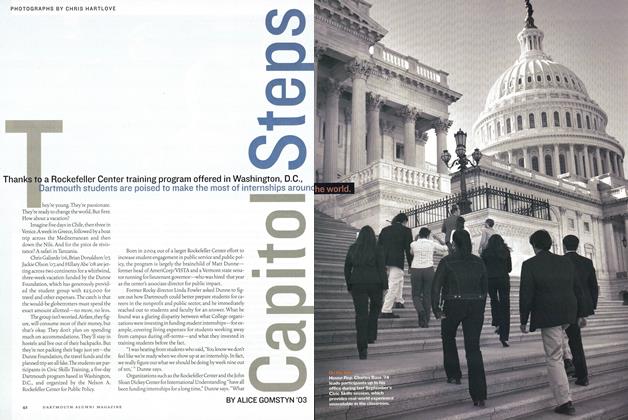

FeatureCapitol Steps

May | June 2006 By ALICE GOMSTYN ’03 -

Feature

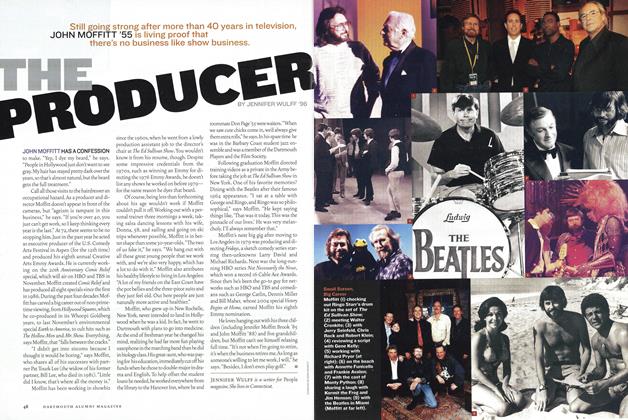

FeatureThe Producer

May | June 2006 By Jennifer Wulff ’96 -

Feature

FeatureNotebook

May | June 2006 By JOE MEHLING '69 -

Feature

FeatureAlumni News

May | June 2006 By Gisela Insuaste '97 -

Article

ArticleNewsmakers

May | June 2006 By BONNIE BARBER -

Article

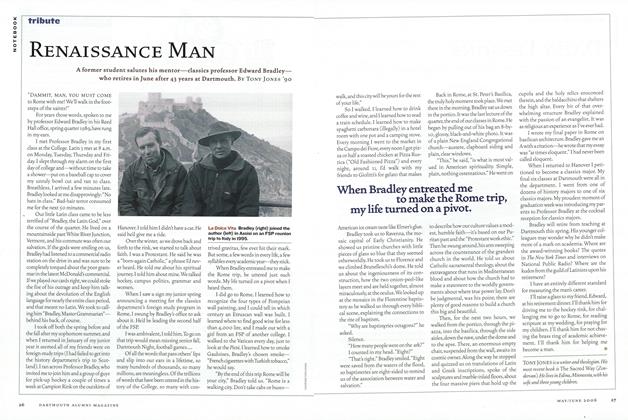

ArticleRenaissance Man

May | June 2006 By TONY JONES '90

JACQUES STEINBERG ’88

-

Feature

FeatureLive From New York!

MAY 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdH. Carl McCall ’58

Sept/Oct 2000 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

Continuing Ed

Continuing EdJohn Hagelin ’76

Mar/Apr 2001 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

Feature

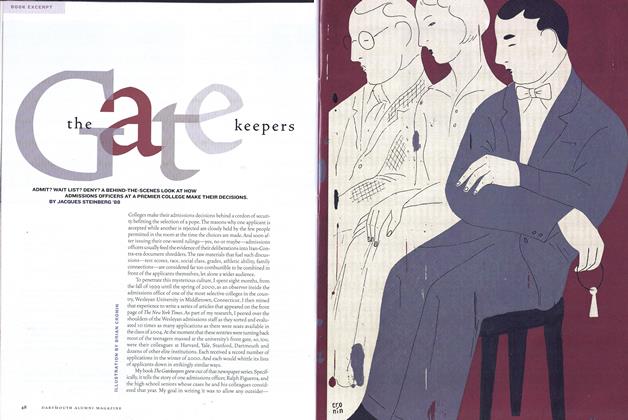

FeatureThe Gatekeepers

Nov/Dec 2002 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88 -

INTERVIEW

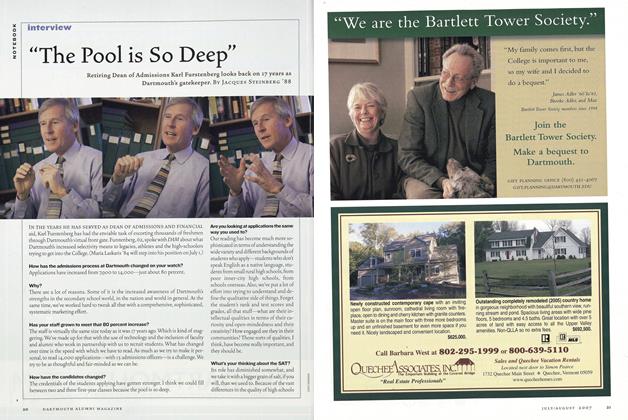

INTERVIEW“The Pool is So Deep”

July/August 2007 By Jacques Steinberg ’88 -

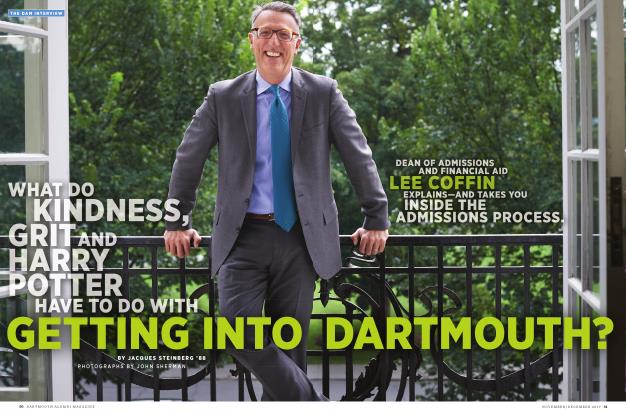

THE DAM INTERVIEW

THE DAM INTERVIEWLee Coffin

NOVEMBER | DECEMBER 2017 By JACQUES STEINBERG ’88