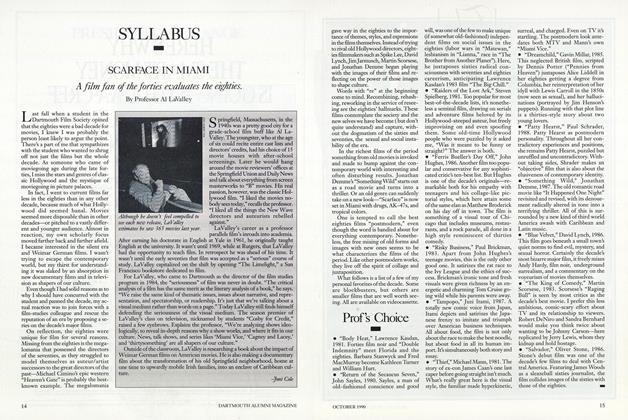

A film fan of the forties evaluates the eighties.

Last fall when a student in the Dartmouth Film Society opined that the eighties were a bad decade for movies, I knew I was probably the person least likely to argue the point. There's a part of me that sympathizes with the student who wanted to shrug off not just the films but the whole decade. As someone who came of moviegoing age during the late forties, I miss the stars and genres of classic Hollywood and the mystique of moviegoing in picture palaces.

In fact, I went to current films far less in the eighties than in any other decade, because much of what Hollywood did seemed banal. Movies seemed more disposable than in other decades—or pitched to a vastly different and younger audience. Almost in reaction, my own scholarly focus moved farther back and farther afield. I became interested in the silent era and Weimar German films. I wasn't trying to escape the contemporary world, but my thirst for understanding it was slaked by an absorption in new documentary films and in television as shapers of our culture.

Even though I had solid reasons as to why I should have concurred with the student and panned the decade, my actual reaction was to join forces with a film-studies colleague and rescue the reputation of an era by proposing a series on the decade's major films.

On reflection, the eighties were unique for film for several reasons. Missing from the eighties is the megalomania that possessed the directors of the seventies, as they struggled to model themselves as auteur/artist successors to the great directors of the past—Michael Cimino's epic western "Heaven's Gate" is probably the bestknown example. The megalomania gave way in the eighties to the importance of themes, styles, and expressions in the films themselves. Instead of trying to rival old Hollywood directors, eighties filmmakers such as Spike Lee, David Lynch, Jim Jarmusch, Martin Scorsese, and Jonathan Demme began playing with the images of their films and reflecting on the power of those images to shape culture.

Words with "re" at the beginning come to mind. Recombining, rehashing, reworking in the service of reseeing are the eighties' hallmarks. These films contemplate the society and the new selves we have become (but don't quite understand) and capture, with- out the dogmatism of the sixties and seventies, the sexual and social instability of the era.

In the richest films of the period something from old movies is invoked and made to bump against the contemporary world with interesting and often disturbing results. Jonathan Demme's "Something Wild" starts out as a road movie and turns into a thriller. Or an old genre can suddenly take on a new 100k "Scarface" is now set in Miami with drugs, AK-47s, and tropical colors.

One is tempted to call the best eighties films "postmodern," even though the word is bandied about for everything contemporary. Nonetheless, the free mixing of old forms and images with new ones seems to be what characterizes the films of the period. Like other postmodern works, they live off the spirit of collage and juxtaposition.

What follows is a list of a few of my personal favorites of the decade. Some are blockbusters, but others are smaller films that are well worth seeing. All are available on videocassette.

Although he doesn't feel compelled tosee each new release, LaValleyestimates he saw 365 movies last year.

Springfield, Massachusetts, in the 1940s was a pretty good city for a grade-school film buff like Al LaValley. The youngster, who at the age of six could recite entire cast lists and directors' credits, had his choice of 15 movie houses with after-school screenings. Later he would hang around the movie reviewers' offices at the Springfield Union and Daily News and talk about everything from screen masterworks to "B" movies. His real passion, however, was the classic Hollywood film. "I liked the movies no- body sees today," recalls the professor. "I liked all the things the New Wave directors and auteurists rebelled against."

LaValley's career as a professor parallels film's inroads into academia. After earning his doctorate in English at Yale in 1961, he originally taught English at the university. It wasn't until 1969, while at Rutgers, that LaValley had the opportunity to teach film. In retrospect he was ahead of his time. It wasn't until the early seventies that film was accepted as a "serious" course of study. LaValley capitalized on the shift by opening "The Limelight," a San Francisco bookstore dedicated to film.

For LaValley, who came to Dartmouth as the director of the film studies program in 1984, the "seriousness" of film was never in doubt. "The critical analysis of a film has the same merit as the literary analysis of a book," he says. "We raise the same kind of thematic issues, issues about narrative, and representation, and spectatorship, or readership. It's just that we're talking about a visual medium rather than words on a page." Today LaValley still finds himself defending the seriousness of the visual medium. The season premier of La Valley's class on television, nicknamed by students "Cosby for Credit," raised a few eyebrows. Explains the professor, "We're analyzing shows ideo- logically, to reveal in-depth reasons why a show works, and where it fits in our culture. News, talk shows, and series likes 'Miami Vice,' 'Cagney and Lacey,' and 'thirty something' are all shapers of our culture."

Outside of the classroom, LaValley is researching a book about the impact of Weimar German films on American movies. He is also making a documentary film about the transformation of his old Springfield neighborhood, home at one time to upwardly mobile Irish families, into an enclave of Caribbean culture.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

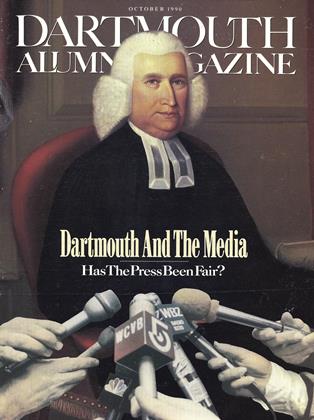

Cover StoryDARTMOUTH IN THE MEDIA

October 1990 By Peter S. Prichard '66 -

Feature

FeatureTHE FORFEIT

October 1990 By Ken Johnson '83 -

Feature

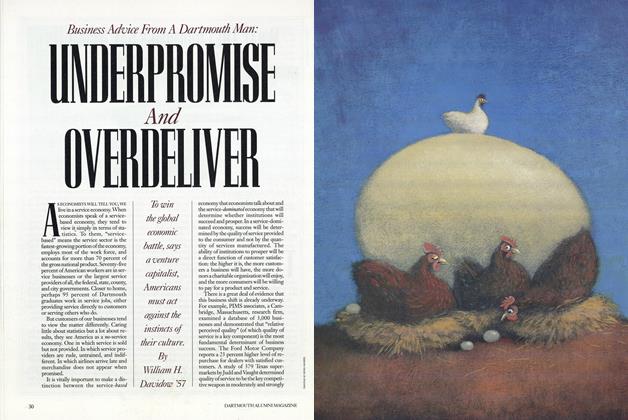

FeatureUNDERPROMISE AND OVERDELIVER

October 1990 By William H. Davidow '57 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

October 1990 By Michael H. Carothers -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

October 1990

Article

-

Article

ArticleMUSICAL CLUBS

February 1919 -

Article

ArticleDOROTHY CANFIELD FISHER FEATURE OF "ARTS" PROGRAM

June, 1923 -

Article

ArticleThree Clocks Are Given In Dr. Baketel's Memory

February 1956 -

Article

ArticleGive a Rouse for —

November 1979 -

Article

ArticleKudos From Green Central

APRIL 1997 -

Article

ArticleImagining the Orient

February 1993 By Douglas Haynes