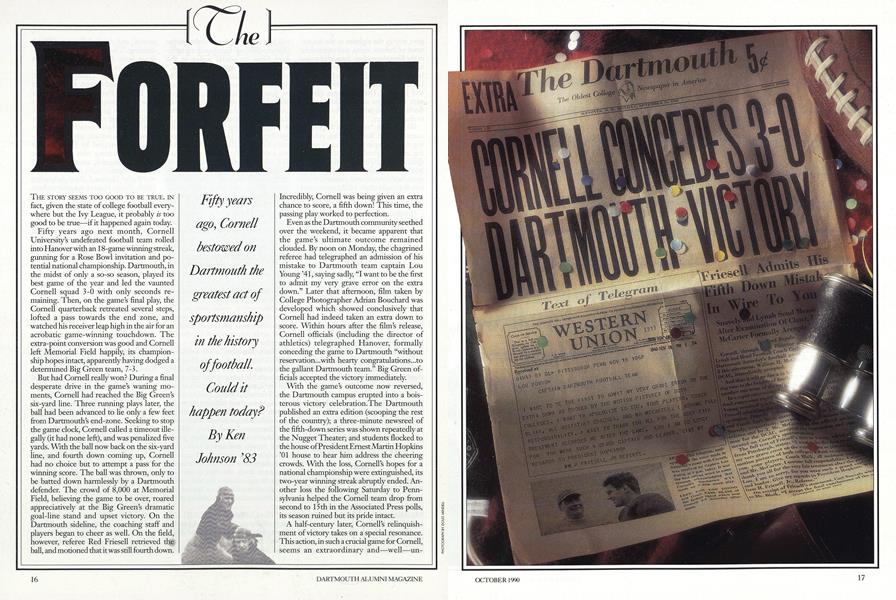

THE STORY SEEMS TOO GOOD TO BE TRUE, IN fact, given the state of college football everywhere but the Ivy League, it probably is too good to be true if it happened again today.

Fifty years ago next month, Cornell University's undefeated football team rolled into Hanover with an 18-game winning streak, gunning for a Rose Bowl invitation and potential national championship. Dartmouth, in the midst of only a so-so season, played its best game of the year and led the vaunted Cornell squad 3-0 with only seconds remaining. Then, on the game's final play, the Cornell quarterback retreated several steps, lofted a pass towards the end zone, and watched his receiver high in the air for an acrobatic game-winning touchdown. The extra-point conversion was good and Cornell left Memorial Field happily, its championship hopes intact, apparently having dodged a determined Big Green team, 7-3.

But had Cornell really won? During a final desperate drive in the game's waning moments, Cornell had reached the Big Green's six-yard line. Three running plays later, the ball had been advanced to lie only a few feet from Dartmouth's end-zone. Seeking to stop the game clock, Cornell called a timeout illegally (it had none left), and was penalized five yards. With the ball now back on the six-yard line, and fourth down coming up, Cornell had no choice but to attempt a pass for the winning score. The ball was thrown, only to be batted down harmlessly by a Dartmouth defender. The crowd of 8,000 at Memorial Field, believing the game to be over, roared appreciatively at the Big Green's dramatic goal-line stand and upset victory. On the Dartmouth sideline, the coaching staff and players began to cheer as well. On the field, however, referee Red Friesell retrieved the ball, and motioned that it was still fourth down. Incredibly, Cornell was being given an extra chance to score, a fifth down! This time, the passing play worked to perfection.

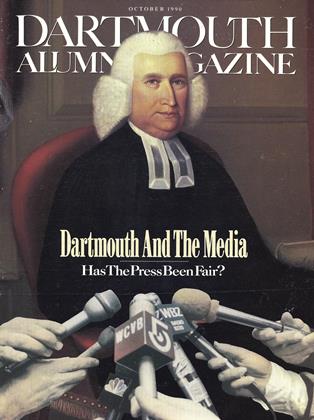

Even as the Dartmouth community seethed over the weekend, it became apparent that the game's ultimate outcome remained clouded. By noon on Monday, the chagrined referee had telegraphed an admission of his mistake to Dartmouth team captain Lou Young '41, saying sadly, "I want to be the first to admit my very grave error on the extra down." Later that afternoon, film taken by College Photographer Adrian Bouchard was developed which showed conclusively that Cornell had indeed taken an extra down to score. Within hours after the film's release, Cornell officials (including the director of athletics) telegraphed Hanover, formally conceding the game to Dartmouth "without reservation...with hearty congratulations...to the gallant Dartmouth team." Big Green officials accepted the victory immediately.

With the game's outcome now reversed, the Dartmouth campus erupted into a boisterous victory celebration.The Dartmouth published an extra edition (scooping the rest of the country); a three-minute newsreel of the fifth-down series was shown repeatedly at the Nugget Theater; and students flocked to the house of President Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 house to hear him address the cheering crowds. With the loss, Cornell's hopes for a national championship were extinguished, its two-year winning streak abruptly ended. Another loss the following Saturday to Penn- sylvania helped the Cornell team drop from second to 15th in the Associated Press polls, its season ruined but its pride intact.

A half-century later, Cornell's relinquishment of victory takes on a special resonance. This action, in such a crucial game for Cornell, seems an extraordinary and—well—un- thinkable gesture of true sportsmanship and self-deprivation. The incident grows even more in stature because it was fully a voluntary decision on Cornell's part. The rules of the Eastern Intercollegiate Athletic Association, which governed the Cornell-Dartmouth game, gave neither the association nor the game officials the authority to adjust the outcome of the contest, regardless of postgame confessions or images on film clips. Cornell's decision was purely self-inflicted, truly heroic (although the cynical among us might note that Cornell's president at the time was Edmund Day, Dartmouth '05), and was hailed by the national news media as a stunning triumph of values over victory. The New York Times wrote, "If we were Cornell, we shouldn't trade that telegram [conceding the game] for all the team's victories in the last two years."

Fifty years after the infamous "fifth down" game, does the ideal of sportsmanship still take precedence over the sheer value of winning? Common sense and a quick check of the sports headlines tell us that few teams in 1990 would give up their national-championship aspirations to correct a bad call. The reason, to put it simply, is money. Winning is too lucrative for most large schools to even consider giving up a game. Bob Sullivan '75, who writes for Sports Illustrated and has covered the investigations of several major college football programs, says that the lure of money has made most big schools blind to everything except victory. "If they're big enough and successful enough that they're competing for a national championship, the mind-set is so pro-winning that they wouldn't even consider giving up a game," Sullivan says.

But in the Ivy League, the emphasis is clearly different. For one thing, there's not as much at stake financially. Although its teams play to win, Dartmouth no longer goes onto the field each weekend with the prospect of a national championship. Despite having a nationally ranked team as late as 1970, Dartmouth has never appeared in a postseason bowl game (see opposite page). Ivy League policies established in 1954 eliminated spring football practice and lucrative athletic scholarships. This may account for Dartmouth's success in standing clear of the scandal in college athletics, but it has also virtually banished Dartmouth from big-time ball.

Eliminating athletic scholarships has hurt the ability of the Ivy League to compete nationally, says Dartmouth head football coach Buddy Teevens '79. Because of the skyrocketing cost of a private school education, many athletes who would consider Dartmouth would rather accept a scholarship at another school. "The better players are going to go where they can go for free," agrees Sullivan.

In contrast with other schools which can redshirt their freshmen in order to give them an extra year's experience, the Ivy League does not allow freshmen to play with the varsity team. And the elimination of spring practice, Teevens adds, costs the team a month's worth of valuable practice time. But as important as winning, Teevens says, is producing the student-athlete, "the guy who strives as hard on the field as he does in the classroom and vice versa," a rare commodity at many big-time universities.

What would a team actually lose by forfeiting a national championship or choosing not to go to the Rose Bowl? "The national championship has no dollar significance to it whatsoever," claims Notre Dame Athletic Director Dick Rosenthal. But he said this just days after Notre Dame chose to sign a $38 million contract with NBC to televise its six home games nationally for the next five years. As for the Rose Bowl itself, since 1947, automatic bids have gone to the champions of the Big Ten and Pac-10 conferences. After last year's game, the two conferences each received $5.5 million, most of which came from an $11.5 million television contract between ABC and the Rose Bowl. (The game itself grossed at least $l6 million from television rights and ticket sales). Each school also received weeks of national media exposure and a national television audience on New Year's Day. In addition to the Rose Bowl, which is still the most prestigious of the bowl games, at least a half-dozen other post-season games (most of which, by the way, decide absolutely nothing) pay teams in excess of $1 million. Would the schools invited to these games dare pass up the opportunity to pad their athletic budgets? Then there are the other benefits. Boston College, for example, reported a dramatic rise in interest in applications to the school as quarterback Doug Flutie was leading the football team to an almost magical rise to national prominence.

The sad truth is that nowadays everything is done in the name of winning. Bob Sullivan investigated a number of schools for Sports Illustrated. "On none of these campuses did I ever get the feeling that people were sorry for what they had done or would consider giving back a game—any game—they had won unfairly, " he reports.

In many Division I schools, the ascendancy of athletics has come at the expense of academic integrity. "The major sports, football and basketball, are the tail wagging the dog," says Dartmouth sociologist Ray Hall. Until 1988, when the NCAA began requiring athletes to meet certain minimum academic standards, SAT scores of 470 out of 1600 were not uncommon.

Moreover, the means by which a young man living in, say, Santa Barbara, decides to go to Norman, Oklahoma, to play football are suspect. Players have testified that they were offered tens of thousands of dollars if they attended certain schools. "Illegal player recruiting," says Ray Hall, "is the most pervasive and pernicious problem in college sports." Once a player arrives on campus, there isn't much evidence at most schools to suggest they will be held responsible for anything unrelated to sports, including academics. Consider this: a nationally ranked university's top wresder, expelled by the faculty for having another student take his final exam, actually had his expulsion commuted by the board of regents.

When cash is king, values are turned upside-down. When Clemson University announced plans to build a learning center for athletes, the football coach said, "This is one of my unhappiest moments at Clemson. They're going to spend $2.5 million on a learning center and you could put that in an athletic dorm." The president of the University of Kentucky resigned under pressure after orchestrating an investigation of the men's basketball program. An academic advisor at the University of Georgia was openly ridiculed after she went public with stories that Bulldog athletes were cheating on exams and having their grades altered. A men's basketball coach at the University of Maryland once visited a woman allegedly raped by one of his players to ask her not to press charges. Sportswriters have been issued death threats. There are countless other examples of sensibilities gone awry, all showing clearly how far values have deteriorated in intercollegiate athletics.

College presidents, having presided over the rise of sports, now face a difficult problem: how to restore values and academic integrity in their schools. The matter will not be easily resolved. Ray Hall points out, "Athletics promote an esprit de corps among alumni. Seventy-five thousand people don't fill a stadium to cheer physics professors." On the other hand, a winning football team might very well help provide the funds to buy those professors a new laboratory. Besides, Sullivan explains that when athletic officials control their departments with an iron fist, some college presidents don't possess the power to give a "fifth down" game back, even if they wanted to.

Maybe it's time for Dartmouth to launch a crusade for the Ivy League to serve as a model for how all athletic programs should be managed. Someday, we may be able to look back on another "fifth-down" situation and and be amazed that old-time values have returned to big-time college football. But until attitudes start to change, this prospect is far off in the future. And so are Dartmouth's (and Cornell's) chances for a top ranking.

Without this newsreel footageof the "fifth Mown" score(above), Cornell might neverhave forfeited its Rose Bowlaspirations. Twenty-fiveyears later, Referees JosephMcKenney and William"Red" Friesell reminiscedwith Cornell captain WalterMatuszak and Dartmouthcaptain Louis Young Jr. '41about the blown call (below).

Ken Johnson is an investment banker in Chicago, secretary of the class of 1983, and an unrepentent sports fan. Whitney Campbell Intern Jonathan Douglas '92 also contributed to this article.

Fifty years ago, Cornell bestowed on Dartmouth the greatest act of sportsmanship in the history of football. Could it happen today?

"Common sense and a quick check of the sports headlines tell us that few teams in 1990 would give up their national championship aspirations to correct a bad call The reason, to put it simply, is money!'

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

Cover StoryDARTMOUTH IN THE MEDIA

October 1990 By Peter S. Prichard '66 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERPROMISE AND OVERDELIVER

October 1990 By William H. Davidow '57 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

October 1990 By Michael H. Carothers -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

October 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

October 1990 By Morton Kondracke

Features

-

Feature

FeatureMUSIC ADVISORY GROUP TO AID HOPKINS CENTER

May 1962 -

Feature

FeatureCommunion With The High Places

September 1992 By Andrew Daniels '85 -

Feature

FeaturePutting Words in the Mouths of the Great

December 1989 By Charles Wheelan ’88 -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By CLARENCE B. RANDALL -

Cover Story

Cover StoryDavid O. Hooke '84

OCTOBER 1997 By Jay Heinrichs '78A -

Feature

FeatureStudent String Quartet

March 1957 By JOHN L. STEWART