The editor of USA Today answers the question: has the press treated the College fairly?

DO SAY THAT THE REVIEW controversy has dominated the media's coverage of Dartmouth College during the past few years is no overstatement.

The fight over The Review has generated much more than letters to the editor of this magazine, though those have been plentiful. There have been dozens of news stories, many picked up by the wire services and published in newspapers across the country. There have been editorials and opinion columns in great national newspapers and tony magazines. What started out as a minor dispute between the College and an infuriating off-campus newspaper written by freshmen and sophomores (and much of the Review's writing is indeed sophomoric) escalated into a bitter battle that attracted national attention.

If there ever was anyone in power at Dartmouth who thought the news media's coverage could be "managed," that hope must have evaporated when "60 Minutes" scheduled the segment titled "Dartmouth vs. Dartmouth." In the media world, if you are seeking publicity, it is quite an accomplishment to get on "60 Minutes." Some publicists salivate at the very suggestion "their story" might make it. But Dartmouth was not featured because of its talented students, its brilliant faculty, or its fine athletic teams. Instead, the College was in the media's brightest spotlight because of a fight with this tiny newspaper, and there was ample mean-spiritedness on both sides. So the Review, which should have been a mere annoyance to the College, was suddenly magnified into a champion of free speech—the little conservative paper that the narrow-minded liberals tried to suppress.

Before the Review fight, Dartmouth got less coverage in the media. Then the College was generally portrayed as a place where bright, well-rounded people got a good liberal education. Its students also parried a lot and watched a fine football team. Some alumni may be nostalgic for the days when that was the College's "image;" for better or worse, that image has changed. Dartmouth cannot be "preserved in amber," to use President Freedman's phrase.

The impression of Dartmouth that emerges from reading three years of press clippings is of a college consumed by the Review controversy, That is almost certainly not accurate, in the sense that much more went on at Dartmouth during those years. But we in the media love conflict, and wittingly or unwittingly, the College gave it to us. And this conflict could not be settled quietly within the confines of the Green: first it spilled over into the courts, then onto the editorial pages of national newspapers, and even the television networks.

Perhaps the fight could have been settled in a quieter way, within the Dartmouth family. Maybe it could have been, if both sides had treated one another with more civility, a too frequendy forgotten virtue. But if civility was in short supply, publicity was plentiful.

This analysis of the media's coverage of Dartmouth tries to answer three questions: (1) Have the media been fair to Dartmouth? (2) Does Dartmouth get more attention than other, similar schools?

(3) Has Dartmouth "deserved" whatever "bum press" it has received, to use Editor Jay Heinrichs's words?

Here, in bullet style (my newspaper is famous for bullets) are my answers, for those of you too busy to read further:

• Most news coverage has been fair. If you read and watch it all, you get a reasonable sense of what happened and a fair idea of both sides' positions.

• The controversy brought Dartmouth more attention than some similar brouhahas at similar schools, but the difference wasn't excessive, or surprising, considering the high profile of the College, some of the alumni, and some of the Review's supporters.

• Dartmouth's administration may have inspired at least part of the coverage by the way it handled the issue, and some of the resulting criticism the College received was probably valid.

• The intense coverage of the Review clash has overshadowed many of the good and important things the College does and probably erased opportunities for "favorable" reporting on these issues.

Many important issues at Dartmouth have gotten less outside attention than they might have. One good example is the College's effort to reduce alcohol abuse, which certainly was too common when I was at Dartmouth from 1962 to 1966, and is still a serious problem for young people and society in general.

Other undercovered issues that come to mind are the College's innovative use of computers throughout the campus, President Freedman's program to attract top students and teachers to Hanover, and the College's campaign to encourage significant academic research by undergraduates. All of these efforts have gotten some regional or even national attention, but in the past few years the space devoted to the Review battle over- whelmed coverage of all other issues, by more than a two-to-one margin.

This analysis of media coverage of the Review controversy divides what's been written into news and opinion pieces. In general, the pieces that ran in the news columns were balanced. The reporters involved usually gave both sides an opportunity to express their points of view. One caveat: the so-called "conservative" publications, from the Union Leader in Manchester to the Washington Times, gave the issue lengthier coverage than other publications did, sometimes leaving the impression that the College was engaged in "conservative-bashing." A few examples:

• When a judge reinstated the suspended Review staffers, the headline in the Washington Times said: "Dartmouth Journalists Returning Unbowed." True, perhaps, but the headline writer enjoyed tilting that title to the right. Another Times head during the court hearing ignored testimony of College officials to seize on that of Jeffrey Hart '51, a Review partisan: "Dartmouth Professor Backs Expelled Editors," the headline said. But the story did note that Hart was a "syndicated columnist" (others called him a "conservative columnist") and that his son Ben '81 was among the Review's founders.

• The Union Leader's headline handled Hart's testimony this way: "Dartmouth President's Remarks on Racism 'Flabbergasted' Prof." The story was fair, although the emotional testimony of Professor William Cole—to me one of the most interesting and emotional parts of the case, since Cole could hardly bear to read what the Review had written about him—was relegated to the ninth paragraph of the story, which ran with the jump on page 18.

• The Wall Street Journal, the nation's largest-circulation newspaper, devoted a good deal of space on its editorial page to quasinews accounts about the controversy. While certainly interesting to Dartmouth graduates, one wonders if spending several columns on this issue was of great interest or import for the Journal's general business readers. It was certainly of great interest to the conservatives who write the Journal's editorials, and Dartmouth graduates who worked for the Review have occasionally written for the Journal. If a college somewhere were accused of persecuting some "liberal" off-campus newspaper, would the Journal devote an equal amount of space to that issue?

Behind the headlines, some of the Union Leader's news coverage was balanced and interesting. One example:

"Dartmouth students had mixed reviews of the paper...Mary Kay McGeown, a senior from New Jersey, wondered if Dartmouth wasn't unfairly getting too much bad publicity.

'"Don't incidents like this take place at other schools?' she asked. McGeown, who described herself as conservative, nonetheless said she keeps her distance from the Review. 'I read it when I was a freshman, but even as a conservative, I no longer want to be associated with it because of the fact that they go overboard.'"

And for those readers interested in a thorough, well-written, and dispassionate account of the whole Review contretemps, read the piece by John Casey, a University of Virginia English professor and noted novelist (Spartina). Casey's article appeared in The New York Times Magazine, February 26, 1989.

Turning to the opinion pages, the editorials were somewhat predictable in the conservative press:

• The New York Post, once well-known for its liberal editorials, is driving its rhetoric from left to right these days: "Alumni concern that the Dartmouth administration had embarked on an ideological vendetta against the Dartmouth Review was heightened last fall when college administrators gave a lavish welcome to Community Party leader Angela Davis...Dartmouth has some serious work to do if it wants to regain the position it held in American academic life." This hyperbolic editorial was based on a report that the Alumni Fund had a slight decline in donors; it failed to note that total funds received from alumni that year were up.

• The Union Leader, which doesn't quite pack the power it did when Bill Loeb was alive and spewing virulence, offered this comparison: "It is easier to corner a field mouse in a round silo than it is to get the Dartmouth administration to acknowledge a demonstrable truth." The Union Leader's position was that the Review students "won" the court case. (I read the Union Leader frequently in the late 19605, but I don't remember many editorials about Dartmouth.)

• The Wall Street Journal, on the intellectual climate at Dartmouth and other "liberal" universities: "It is an atmosphere that is not liberal. It is sneering, condescending and intolerant of uncongenial views."

Perhaps the heaviest blow against the way the administration handled the matter came from Laurence Silberman '57, a U.S. Appeals Court judge. He declined an alumni club award, noting that "the whole [Review] episode took place against a backdrop of undisguised hostility to the political views expressed in the Dartmouth Review" and he objected to "the polemical and excessive terms in which those opinions were sometimes cast" by the College. The Wall Street Journal printed the entire text of Silberman's letter turning down the alumni award.

Conservative columnist James Kilpatrick concluded that Dartmouth "behaved shamefully. Only the most devoted friends of this small college could love it now."

I could not find many editorials supporting the administration's handling of the Review. An essay in Time by Garry Wills noted that "The right-wing Dartmouth Review and its imitators have understandably infuriated liberals. " But Wills went on to say that "neither does the law come in to silence Tipper Gore or Frank Zappa or even that filthy rag, the Dartmouth Review."

Nat Hentoff, the columnist who is a champion of free speech and a leading expert on the issue, wrote: "The Dartmouth Review is indeed often outrageous, tasteless and cruel. It also is unabashedly right wing. The periodical is, however, within the vintage of American tradition of savagely satirical polemics. " Hentoff recalled "the depiction in his time, for example, of Thomas Jefferson as the proprietor of a slave harem who is auctioning his own mulatto child into slavery. As Judge Silberman recognized, this is a test of Dartmouth's ability to deal with speech that it hates."

The College did not always pass that test. Jeffrey Hart, a Review partisan, testified during the hearing that a former dean had urged College employees not to talk to Review reporters, a College employee had thrown free copies of the Review into the trash, and that the College had banned distribution of the Review at football games.

So why did this little battle become such a big war in the first place? Like it or not, higher education is a hot, controversial topic. With the annual tab now above $20,000 at most elite colleges, public interest is high in any story that suggests not everyone gets their money's worth. The public probably already believes that, so in attacking parts of Dartmouth's curriculum the Review's writers were playing to popular prejudice and they knew it.

The Review's writers, and their media-sawy conservative mentors, obviously love needling the "liberal elitists" in charge. The mentors welcome any chance to annoy that establishment, and they probably also recognized that these college sophomores had more liberty to be outrageous than any middle-aged pundit could dare to be. From their point of view, a David vs. Goliath, conservative vs. liberal issue like the Review vs. Dartmouth was irresistible, a no-lose cause to bankroll and poleniicize.

Many of these mentors, from Jeffrey Hart to William Buckley, are scarred veterans of various vicious academic and intellectual skirmishes. They marched to the front with predictable relish, especially when they had a chance to pin the "McCarthyism" label on the Dartmouth establishment. Because there was some truth to the charge and because the College attacked the Review so strenuously it was natural for the fight to evolve from the op-ed pages to prime time.

The Review was surely a vexing test for the College. There is no doubt that much of what the Review published was scurrilous, racist, and hurtful. If the College had stuck to fighting speech with speech, and avoided getting into a war with the Review, would the result have been different?

Bruce Mohl, the New Hampshire judge who decided the students should be reinstated after their encounter with Professor Cole, wrote: "It cannot help but be noted that had greater civility and less discourtesy been observed by all the participants in that brief encounter on February 25, 1988, such an exhaustive expenditure of human and financial assets might well have been avoided."

One lesson is clear: once the conflict spilled off the Green and into the courts, the media stampede to cover a messy battle at an idyllic Ivy League school was inevitable. When Dartmouth is in the news in the future, my hope is we will read less about conflict and more about community.

If the powers that beever thought theycould "manage "coverage of theCollege, that hopeevaporated whenMorley Safer came totown to do a "60Minutes " segmententitled "Dartmouthvs. Dartmouth."

When Judge Silbermanturned down an alumniaward, The Wall StreetJournal printed theentire text of his letter.

"In the past few years the space devoted to the Review battle overwhelmed coverage of all other issues, by more than a two-to-one margin

"Dartmouth's administration may have inspired at least part of the coverage by the way it handled the issue, and some of the resulting criticism the College received was probably valid!'

Editor of USA Today, Peter Prichard is also the author of The Making of McPaper: The In-side story of USA Today.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

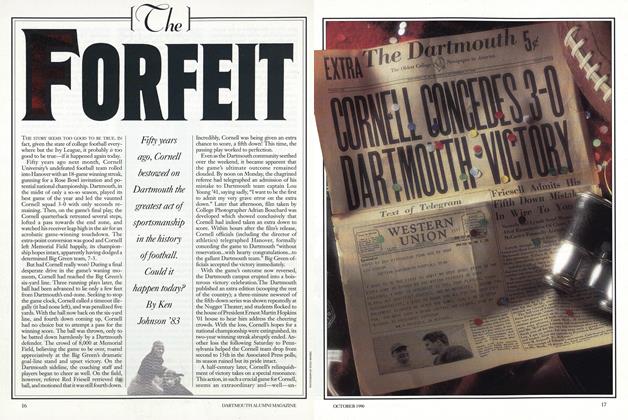

FeatureTHE FORFEIT

October 1990 By Ken Johnson '83 -

Feature

FeatureUNDERPROMISE AND OVERDELIVER

October 1990 By William H. Davidow '57 -

Article

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

October 1990 -

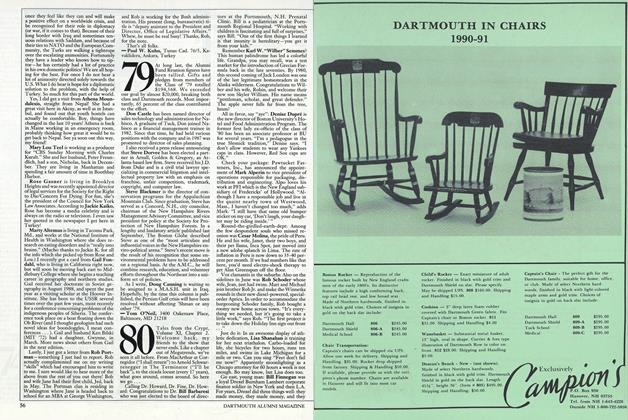

Class Notes

Class Notes1980

October 1990 By Michael H. Carothers -

Article

ArticleProf's Choice

October 1990 -

Class Notes

Class Notes1960

October 1990 By Morton Kondracke

Features

-

Feature

FeatureTHE BEGINNINGS of Dartmouth's Alumni Organization

March 1955 By ERNEST MARTIN HOPKINS 01 -

Feature

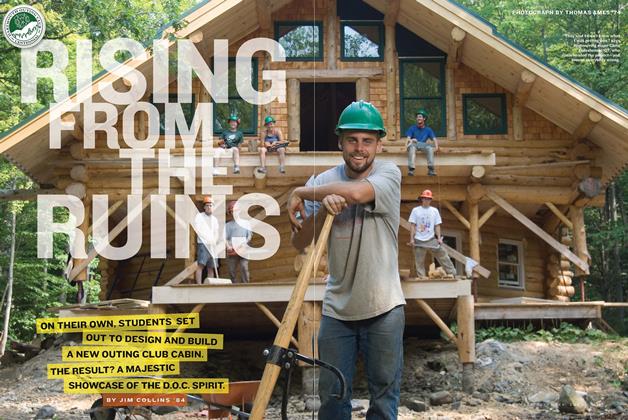

FeatureRising From the Ruins

Nov/Dec 2009 By JIM COLLINS ’84 -

Feature

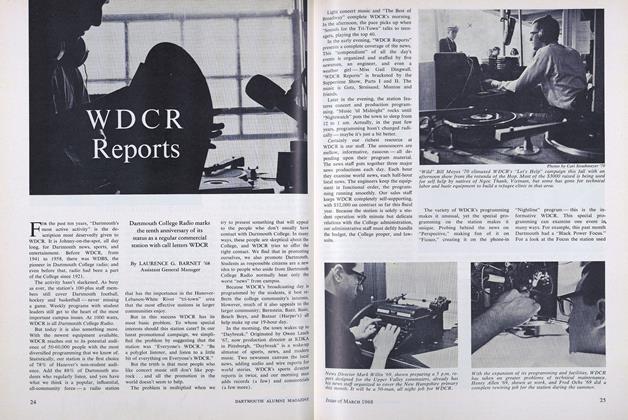

FeatureWDCR Reports

MARCH 1968 By LAURENCE G. BARNET '68 -

Feature

FeatureOliver Wendell Holmes Slept – and Taught – Here

May 1956 By ROBERT S. BLUM '55