"Our bias towardWestern culture limitsour capacity to trade inideas no less than inservices and products."

As THE AMERICAN DIPLOMATIC Establishment frets about Mikhail Gorbachev's ability to carry out his mission or even to survive in office the most sophisticated efforts are made to decipher every nuance of his words and actions. It would be more rewarding if Americans decided to pay attention to learning the language and studying the culture of Gorbachev's people. That would require an act of glasnost of our own to remove our national blinders on the study of foreign languages and of non-Western cultures.

As a college president, I have often told students that a liberal education is "the surest instrument that Western civilization has yet devised for preparing men and women to lead productive and satisfying lives." Yet looking back, I now wonder whether that confident declaration was not too narrowly framed.

An unqualified emphasis upon "Western civilization" blocks access to non-Western cultures and legitimates an assumption of European and American cultural superiority. That assumption stands in tie path of a better understanding of the Soviet Union. It is as damaging to our nation as it is menacing to the world that our students will be compelled to understand and to shape.

This is precisely the time, when a number of voices in American life are suggesting that college courses be devoted almost exclusively to Western literature, that we should be looking far beyond our own culture. We need to worry, as Professor Allan Bloom has reminded us, about "the closing of the American mind," but we should worry as well about the opening of the American mind.

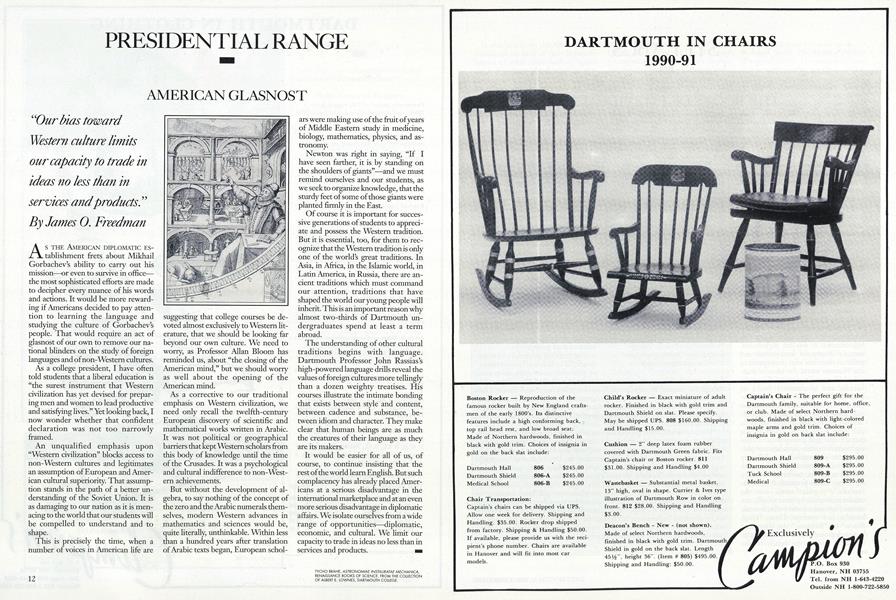

As a corrective to our traditional emphasis on Western civilization, we need only recall the twelfth-century European discovery of scientific and mathematical works written in Arabic. It was not political or geographical barriers that kept Western scholars from this body of knowledge until the time of the Crusades. It was a psychological and cultural indifference to non-Western achievements.

But without the development of algebra, to say nothing of the concept of the zero and the Arabic numerals themselves, modern Western advances in mathematics and sciences would be, quite literally, unthinkable. Within less than a hundred years after translation of Arabic texts began, European scholars were making use of the fruit of years of Middle Eastern study in medicine, biology, mathematics, physics, and astronomy.

Newton was right in saying, "If I have seen farther, it is by standing on the shoulders of giants" and we must remind ourselves and our students, as we seek to organize knowledge, that the sturdy feet of some of those giants were planted firmly in the East.

Of course it is important for successive generations of students to appreciate and possess the Western tradition. But it is essential, too, for them to recognize that the Western tradition is only one of the world's great traditions. In Asia, in Africa, in the Islamic world, in Latin America, in Russia, there are ancient traditions which must command our attention, traditions that have shaped the world our young people will inherit. This is an important reason why almost two-thirds of Dartmouth undergraduates spend at least a term abroad.

The understanding of other cultural traditions begins with language. Dartmouth Professor John Rassias's high-powered language drills reveal the values of foreign cultures more tellingly than a dozen weighty treatises. His courses illustrate the intimate bonding that exists between style and content, between cadence and substance, between idiom and character. They make clear that human beings are as much the creatures of their language as they are its makers.

It would be easier for all of us, of course, to continue insisting that the rest of the world learn English. But such complacency has already placed Americans at a serious disadvantage in the international marketplace and at an even more serious disadvantage in diplomatic affairs. We isolate ourselves from a wide range of opportunities diplomatic, economic, and cultural. We limit our capacity to trade in ideas no less than in services and products.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureShrink Rap

November 1990 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

FeatureLIVING THE LIFE OF THE MIND

November 1990 By Cynthia Richards '90 -

Feature

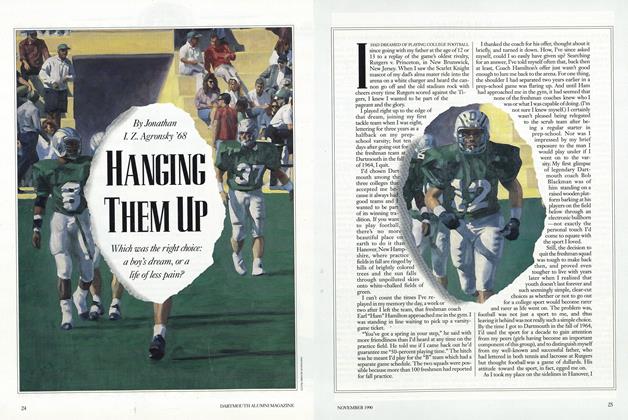

FeatureHanging Them Up

November 1990 By Jonathan I. Z. Agronsky '68 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHorace Fletcher 1870

November 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWalter F. Wanger 1915

November 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Ledyard 1776

November 1990

Article

-

Article

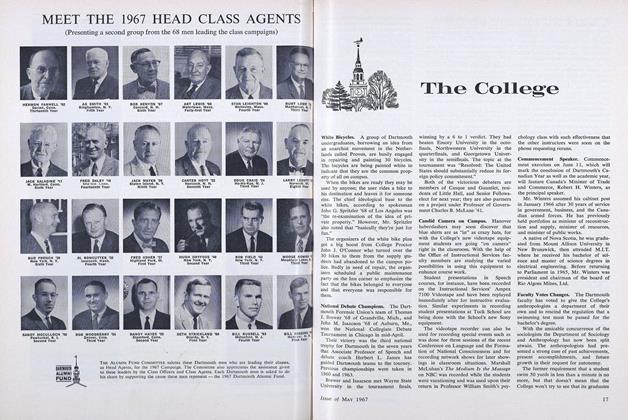

ArticleCommencement Speaker.

MAY 1967 -

Article

ArticleRecord-Breaking Weather

JANUARY 1997 -

Article

ArticleThe Archivist Orchidist

Mar/Apr 2013 -

Article

ArticleBAVARIAN SKIERS COMING

January 1938 By Ben Ames Williams Jr. '38 -

Article

ArticleSnowed In—But Not Under

December 1947 By JOHN HURD '21 -

Article

ArticleGreeting

MAY 1931 By Wendell Phillips Stafford