Which was the right choice:a boy's dream, or alife of less pain?

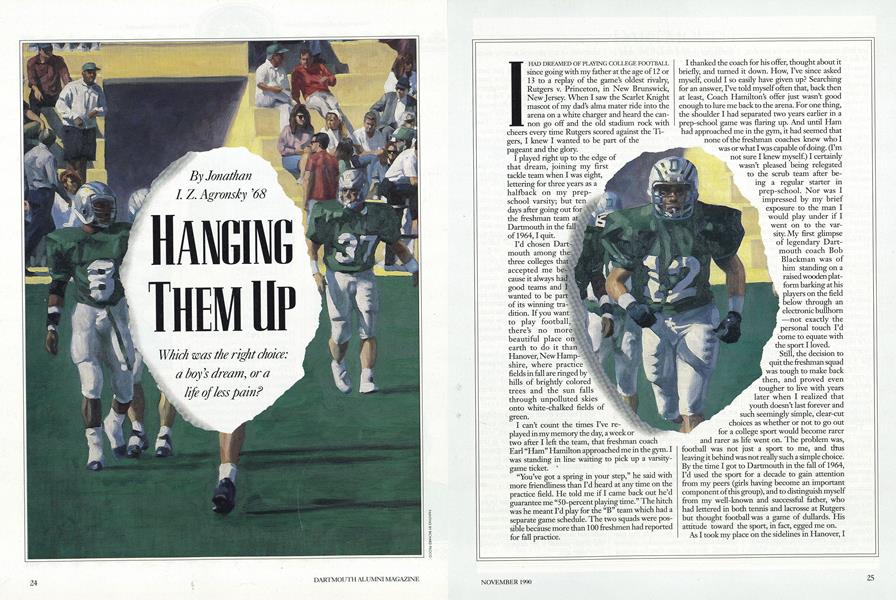

I HAD DREAMED OF PLAYING COLLEGE FOOTBALL since going with my father at the age of 12 or 13 to a replay of the game's oldest rivalry, Rutgers v. Princeton, in New Brunswick, New Jersey When I saw the Scarlet Knight mascot of my dad's alma mater ride into the arena on a white charger and heard the cannon go off and the old stadium rock with cheers every time Rutgers scored against the Tigers, I knew I wanted to be part of the pageant and the glory.

I played right up to the edge of that dream, joining my first tackle team when I was eight, lettering for three years as a halfback on my prepschool varsity; but ten days after going out for the freshman team at Dartmouth in the fall of 1964, I quit.

I'd chosen Dartmouth among the three colleges that accepted me because it always had good teams and I wanted to be part of its winning tradition. If you want to play football there's no more beautiful place on earth to do it than Hanover, New Hampshire, where practice fields in fall are ringed by hills of brightly colored trees and the sun falls through unpolluted skies onto white-chalked fields of green.

I can't count the times I've replayed in my memory the day, a week or two after I left the team, that freshman coach Earl "Ham" Hamilton approached me in the gym. I was standing in line waiting to pick up a varsity-game ticket

"You've got a spring in your step," he said with more friendliness than I'd heard at any time on the practice field. He told me if I came back out he'd guarantee me "50-percent playing time." The hitch was he meant I'd play for the "B" team which had a separate game schedule. The two squads were possible because more than 100 freshmen had reported for fall practice.

I thanked the coach for his offer, thought about it briefly, and turned it down. How, I've since asked myself, could I so easily have given up? Searching for an answer, I've told myself often that, back then at least, Coach Hamilton's offer just wasn't good enough to lure me back to the arena. For one thing, the shoulder I had separated two years earlier in a prep-school game was flaring up. And until Ham had approached me in the gym, it had seemed that none of the freshman coaches knew who I was or what I was capable of doing. (I'm not sure I knew myself.) I certainly wasn't pleased being relegated to the scrub team after being a regular starter in prep-school. Nor was I impressed by my brief exposure to the man I would play under if I went on to the varsity. My first glimpse of legendary Dartmouth coach Bob Blackman was of him standing on a raised wooden platform barking at his players on the field below through an electronic bullhorn not exactly the personal touch I'd come to equate with the sport I loved.

As I took my place on the sidelines in Hanover, I got little consolation from the fact that, of the 800 or so members of my freshman class, the Dartmouth class of 1968, more than 220 had captained their prep or high-school football teams. Nor did it make much difference to my bruised 18-year-old ego that the freshman team I had joined briefly was loaded with talent, particularly in the backfield where I played: Gordon Rule, for instance, would be named honorablemention All-American his senior year and later would play cornerback for the Green Bay Packers; Eugene Ryzewicz, about my size at 5'9", 168 pounds, would key Dartmouth's 1965 championship season alternating at halfback and quarterback and would be named honorable-mention All-Ivy the following year; Steve Luxford, a slashing power runner who had been an allmetropolitan selection in my home city of Washington, D.C., would be named Dartmouth's team captain his senior year; defensive back Sam Hawken, a boyhood friend from D.C. whom I'd played against in prep school, would earn honorable-mention All-Ivy, All-East, and All-New England honors his junior: year; perhaps the most talented freshman back George Spivey, one of a handful of blacks on the team, would enter the end zone frequently while displaying the speed and fluid grace of a Walter Payton (but George, sadly, would tear a hamstring muscle during a pre-season scrimmage the following summer, ending his varsity career before it ever got started). Nor did I generate much face-saving pride by captaining dorm and fraternity touch squads or winning two campus-wide football-skills contests with record-breaking passes and punts.

These things added up to spit compared to the glory I'd voluntarily surrendered.

As it turned out, the freshman squad I quit posted an 8-1 record and over the next three years developed into one of the best football teams in Dartmouth history, winning the Ivy championship and the Lambert Trophy in 1965 with a 9-1 record, dominating its Ivy and non-Ivy opponents and getting nationally ranked for the first time in decades. (Penn State's Joe Paterno, miffed by the ranking, challenged Bob Blackman to a post-season game, to which Blackman replied that, if he were to break the Ivy League rule banning post-season play, it would be against a team with a better record than the Nittany Lions had.)

I felt intensely ambivalent sitting in the stands watching my classmates compete. My rational self told me my decision had been "mature," that it was time to start preparing myself to compete in life's larger arenas. But a less friendly inner voice accused me of being a "quitter"; it urged me, unsuccessfully, to put aside my concerns and re-enter the arena. That voice was reinforced by my passion for the game. There was something about being on that aptly named gridiron, dressed for combat, lampblack smeared under my eyes like war paint, adrenalin pumping through my system, being watched and cheered by thousands with the game riding on my actions, the feel of the pigskin; about throwing myself headlong into an opponent and both of us getting up again after the play most of the time that made me want to postpone hanging up my cleats forever. Unfortunately, my physical state didn't quite jibe with my passion: besides separating my shoulder, I also had severely sprained an ankle and damaged the disks in my lower back playing football.

Ironically, it was one of my former Dartmouth teammates, my orthopedist these days, who helped me finally make peace with the choice that I had made more than a quarter of a century ago. (Well, maybe not peace, but at least I coexist more easily now with the words I still hear with haunting regularity after all these years: "You've got a spring in your step.")

I'd been coming to Dr. Sam Hawken for treatment of various painful manifestations of post-adolescent macho syndrome: a wrist sprained flying over the handlebars of a motor scooter at a Club Med; a lower back sprained playing coed volleyball; an ankle fractured while jogging at night on the sidewalks of Georgetown. During one of those visits, I learned that this ruggedly built man who'd stayed in the limelight three years longer than I had paid an even higher price. He had sustained such serious injuries playing football, he told me, that he is now incapable of any physical activity more strenuous than gardening.

I remember the play that put Sam out of action. It was our junior year, in the final quarter of the last game of the 1966 season against Penn at Franklin Field. The Indians, who would become Ivy co-champions that year, were leading the Quakers 34-21. The Quakers were deep in their own territory facing a fourth down. They sent in their second-string quarterback who also did their punting. But when he received the ball he cocked his arm, not his leg, and threw a pass. Sam intercepted it on the 40-yard line. He streaked down the sideline, with a clear path to the goal. But at the "two-yard line, the Penn signal-caller, who had much to make up for, caught up with him and hit him low from the side. Sam's momentum carried him into the end zone, but the tackle had pulverized his knee, severing three of four tendons and putting the future physician on crutches for six months. Although Sam later played rugby during medical school, wearing a knee brace, and played competitive tennis into his late thirties, the injury he sustained at Franklin Field not only ended his football career, it so weakened his knee joint that it wore out early, forcing Sam to limit his physical activities today.

When Sam told me his story, I realized that my decision to leave the game early, however upsetting, had not been altogether unwise. With my body relatively intact, I, at least, can swim now and, on good days, when my lower back is not acting up, run.

But I think I'd still trade my relative health and mobility for a chance to go back and make that freshman team again, and maybe take my shot at the varsity. Sometimes, when the gauntlet's thrown down, you've got to just pick it up and run with it. It's a chance, and a moment, that may never come again.

Jonathan I. Z. Agronsky is a reporter forthe Voice of America in Washington. He isalso writing a book about D.C. ex-mayorMarion Barry. Agronsky's father, veterantelevision journalist Martin Agronsky whostill thinks football is for dullards, retiredthree years ago.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

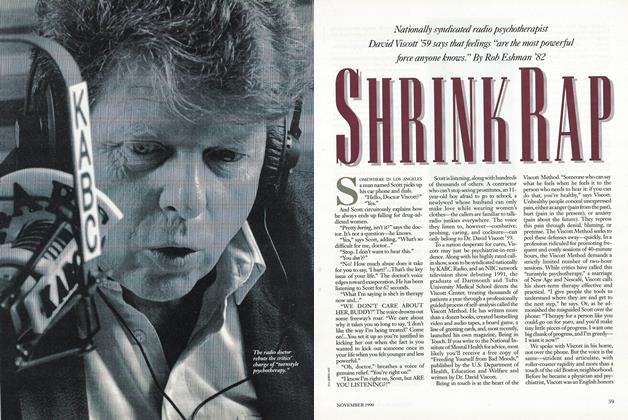

FeatureShrink Rap

November 1990 By Rob Eshman '82 -

Feature

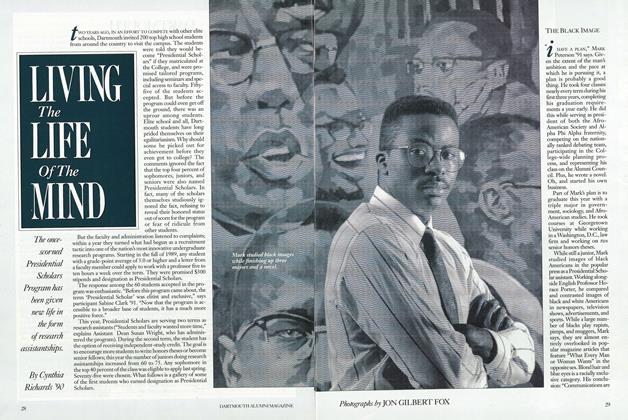

FeatureLIVING THE LIFE OF THE MIND

November 1990 By Cynthia Richards '90 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryHorace Fletcher 1870

November 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryWalter F. Wanger 1915

November 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryJohn Ledyard 1776

November 1990 -

Cover Story

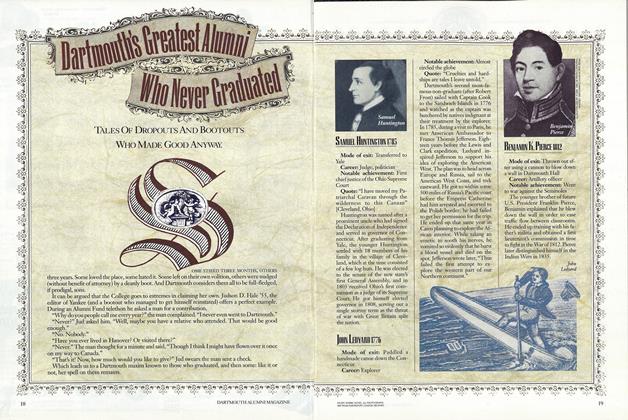

Cover StoryTales of Dropouts And Bootouts Who Made Good Anyway.

November 1990

Features

-

Feature

FeatureCoeducation

April 1975 -

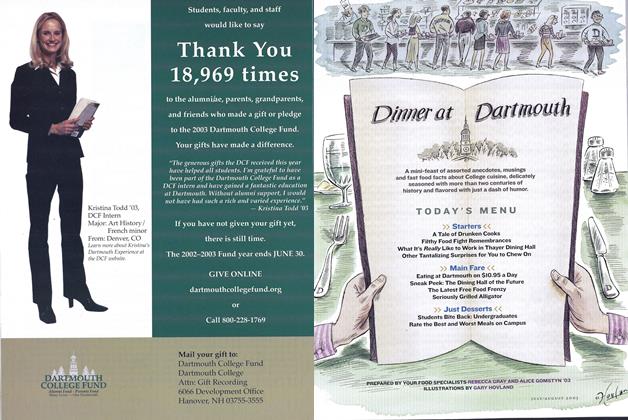

Feature

FeatureDinner at Dartmouth

July/Aug 2003 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE SPIRIT OF ADVENTURE

Jan/Feb 2013 -

Feature

FeatureArt Exhibits

MAY 1957 By PROF. CHURCHILL P. LATHROP -

Feature

FeatureA Basic Classical Library

January 1960 By PROF. ROBIN ROBINSON '24 -

Feature

FeatureFirst Panel Discussion

October 1951 By SIDNEY E. SMITH