Lack of food isn't the problem.

There are 600,000 severely undernourished children walking the streets today in Sao Paulo, Brazil. None of these children is the victim of war or of any natural or man-made environmental catastrophe. Their dire situation is repeated in almost all of the cities of the Third World and many developed nations. Annually, between ten and 20 million people most of them children die of the direct or proximate effects of starvation. Every year between 500 million and one billion people who don't die suffer acute malnutrition, chronic undernutrition, or both.

And yet fewer than half of these people are the victims of famine. Food shortages caused by natural catastrophes or war, lamentable as they are, account for only a small part of the problem. Nor is the problem caused by there being too many mouths to feed and too little food to go around. Even though population expansion, if left unchecked, will eventually outstrip resources, it is not the cause of today's widespread hunger. For at least the past decade, enough food has been produced worldwide to provide an ample 3,000 calories per day for every person on the planet.

The problem is that many people cannot control the conditions of their lives; they are too poor to buy food and have no access to land to produce their own food. How can the political and economic arrangements of the modern world produce poverty in such extreme form that one-sixth of the world's population is chronically hungry?

Most undergraduates assume that economic development implies a general rise in living standards. They are surprised to learn that almost all of the potential welfare benefit of a Third World country's economic development accrues to households that are already in the wealthiest segment. And they are surprised to learn that Western-style economic development often produces new levels and forms of poverty abroad.

Ironically, although the world's wealth as measured in gross national product doubles every quarter century, poverty and landlessness are on the rise in many parts of the world. As has happened in Asia and Latin America, many landowners shift from growing subsistence crops for local consumption to producing cash crops often unedible for export. The shift entails overhauling their means of farming: they mechanize production and either evict tenant farmers or hire them as wage laborers. The result is that people who used to grow their own food are now forced to purchase it often paying high prices for nutritionally inadequate imported starches. Many farmers use their land as collateral for loans in order to pay the enormous startup costs of cash-crop agriculture for modern equipment, hybrid seeds, fertilizer. If they default on their loans, they lose their land. When multinational corporations buy up such property, local residents may permanently lose access to the arable fields around them. In Africa, the Philippines, and elsewhere, decreases in the land available for subsistence farming have spurred massive migrations from rural areas to urban job markets. The resultant glut of urban workers keeps wages low. Workers have no alternatives, and their families continue to go hungry.

If aggregate national growth has not reduced worldwide hunger, what will?

A promising solution lies in bolstering traditional systems of production and self-sufficiency. Many non-governmental bodies, including the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations, are increasingly encouraging small-scale subsistence farming rather than further consolidation of smallholdings into large-scale commodities farming. In Latin America and Asia especially, this means massive redistribution of land. But the payoffs can be significant. The entire African nation of Botswana, for example, could be fed if each of the country's 80,000 farm households could cultivate just 15 acres or could increase slightly the yields from smaller plots, both attainable goals. Scientific farming techniques can be combined with local resources to increase yields without requiring cash inputs. Farmers can use drip irrigation instead of more expensive schemes, compost instead of purchased fertilizers, and ash instead of chemical pesticides. They can plant local seeds adapted to the specific ecology rather than hybrids that must be purchased each year. Local opportunities for small-scale producers of food and goods to market their products to each other and their urban counterparts would allow farmers and wage earners to avoid dependence on a world market that is beyond their means.

The fostering of small-scale farming would have the wider effect of raising wages in the urban sector. If rural populations can feed themselves and grow enough cash crops to meet minimum cash requirements, farmers would migrate to cities only if formal-sector wages provided a standard of living at least equivalent to the return from subsistence farming. The power to subsist to refuse work that pays sub-subsistence wages is the best assurance that wages paid in the formal sector of national economies will be adequate to provide enough food for a decent life.

More of the world should be eating, notexporting, what it grows, according toanthropologist Hoyt Alverson.

Anthropology Professor Hoyt Alverson's interest in small-scale farming as a solution to world hunger is rooted in the soil of rural Botswana, where he spent three years studying labor migration and its effect on rural communities. Living in a village close to Botswana's largest agricultural research station, he observed the gap between the station's recommendations for development and the realities of people's lives. "The researchers thought that farmers should change everything they do, from the seeds they plant to the equipment they use," says Alverson. "Yet farmers just down the road were too poor for this approach. I came to see that the efficiency and effectiveness of food production can be increased without extensive cost and upheaval if we build upon rather than scrap traditional ways. We should regard the empirical knowledge that other culture have developed over the centuries as a tremendous resource. Alverson's course on the politics of hunger plunges Dartmouth students into the conditions of poverty that exist in the shadows of the College. He requires students to work for a week in the homeless shelters and soup kitchens of the Upper Valley and Boston, then write up their findings. Two years ago several students went far beyond the assignment. They used their new-found knowledge to organize a food redistribution progam called FAMINE that has since become part of the Tucker Foundation. A Yale Ph.D. who specializes in linguistics as well as economic anthropology, Alverson frequently lectures outside the undergraduate classroom. He has shown numerous corporations, government agencies, and executives at the Dartmouth Institute that understanding the concept of culture makes good business sense. Says the professor, "Anthropology shows us that what seems rational and efficient in terms of prices may be disastrous in terms of human culture. Part of organizing production involves understanding that within an organization you create a culture with its own ecology, institutional arrangements, ideology, values. These often exist in opposition to the assumptions and premises of rational decision-making. To increase efficiency and assess risk, firms should look at what will or won't work in terms of the culture of the organization and keep in mind that sometimes the culture of the organization itself should be changed." Karen Endicott

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

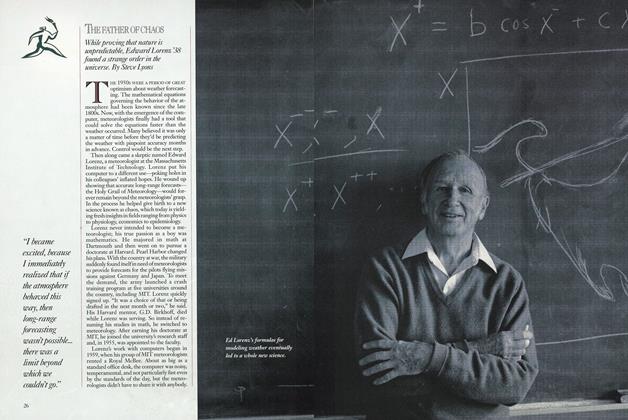

Cover StoryTHE FATHER OF CHAOS

June 1990 By Steve Lyons -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE DOCTOR FOR THE SPIRIT

June 1990 By Elise Miller ’85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE JUDGE WHO METES COMFORT

June 1990 By Jack Steinberg ’88 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryTHE MEDICAL SYSTEM’S EMERGENCY SURGEON

June 1990 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

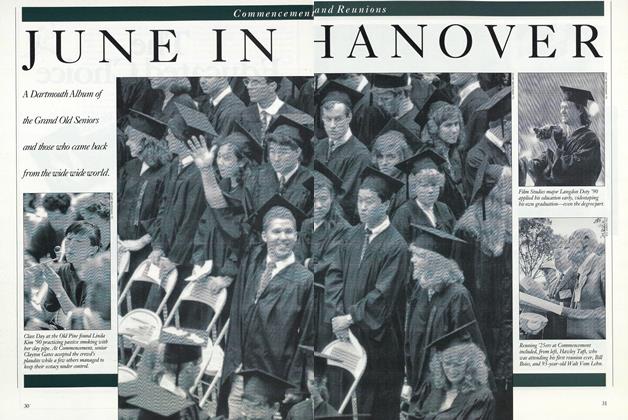

FeatureJUNE IN HANOVER

June 1990 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryVoices Crying In The Wilderness

June 1990 By The Editors