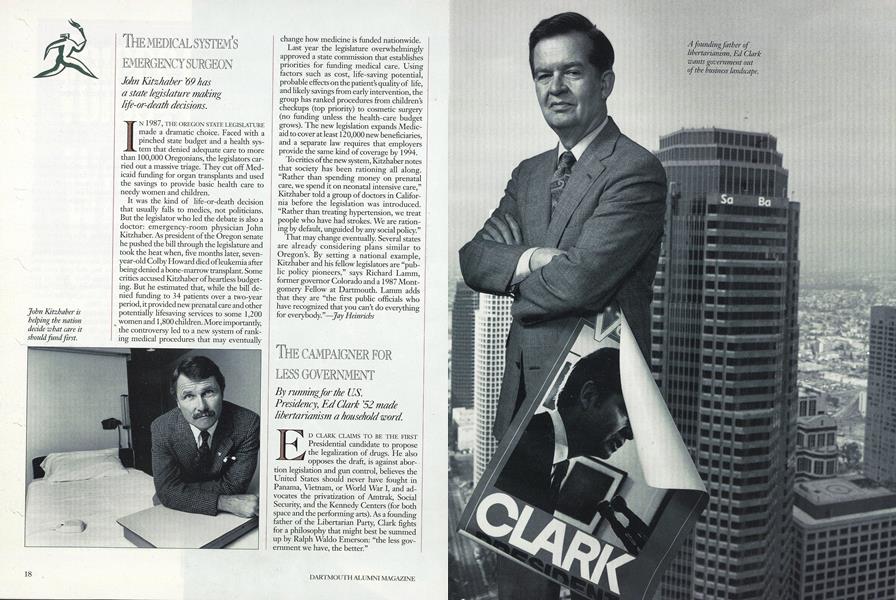

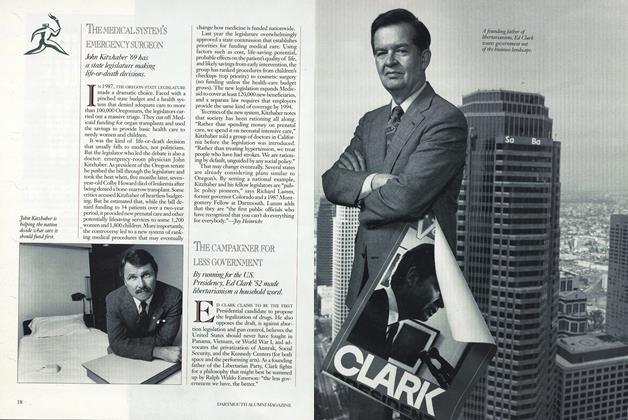

John Kitzhaber 69 hasa state legislature makinglife-or-death decisions.

IN 1987, THE OREGON STATE LEGISLATURE made a dramatic choice. Faced with a pinched state budget and a health system that denied adequate care to more than 100,000 Oregonianes, the legislators carried out a massive triage. They cut off Medicaid funding for organ transplants and used the savings to provide basic health care to needy women and children.

It was the kind of life-or-death decision that usually falls to medics, not politicians. But the legislator who led the debate is also a doctor: emergency-room physician John Kitzhaber. As president of the Oregon senate he pushed the bill through the legislature and took the heat when, five months later, seven-year-old Colby Howard died of leukemia after being denied a bone-marrow transplant. Some critics accused Kitzhaber of heartless budgeting. But he estimated that, while the bill denied funding to 34 patients over a two-year period, it provided new prenatal care and other potentially lifesaving services to some 1,200 women and 1,800 children. More importantly, the controversy led to a new system of ranking medical procedures that may eventually change how medicine is funded nationwide.

Last year the legislature overwhelmingly approved a state commission that establishes priorities for funding medical care. Using factors such as cost, life-saving potential, probable effects on the patient's quality of life, and likely savings from early intervention, the group has ranked procedures from children's checkups (top priority) to cosmetic surgery (no funding unless the health-care budget grows). The new legislation expands Medicaid to cover at least 120,000 new beneficiaries, and a separate law requires that employers provide the same kind of coverage by 1994.

To critics of the new system, Kitzhaber notes that society has been rationing all along. "Rather than spending money on prenatal care, we spend it on neonatal intensive care," Kitzhaber told a group of doctors in California before the legislation was introduced. "Rather than treating hypertension, we treat people who have had strokes. We are rationing by default, unguided by any social policy."

That may change eventually. Several states are already considering plans similar to Oregon's. By setting a national example, Kitzhaber and his fellow legislators are "public policy pioneers," says Richard Lamm, former governor Colorado and a 1987 Montgomery Fellow at Dartmouth. Lamm adds that they are "the first public officials who have recognized that you can't do everything for everybody."

John Kitzhaber ishelping the nationdecide what care itshould fund first.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Cover Story

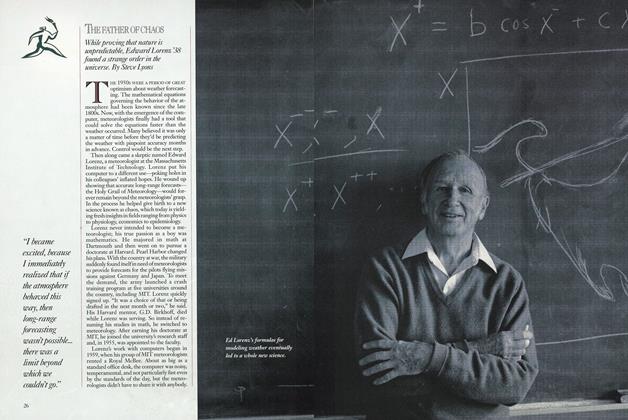

Cover StoryTHE FATHER OF CHAOS

June 1990 By Steve Lyons -

Cover Story

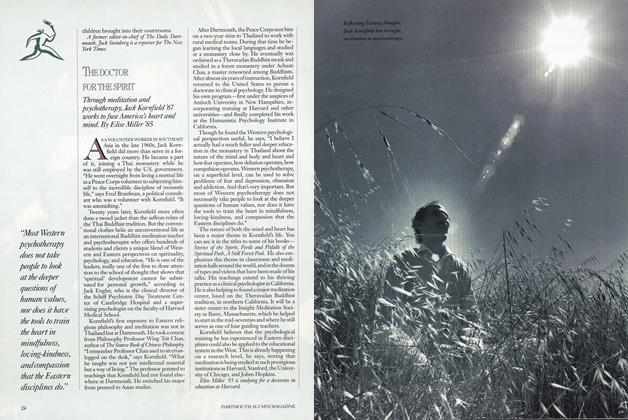

Cover StoryTHE DOCTOR FOR THE SPIRIT

June 1990 By Elise Miller ’85 -

Cover Story

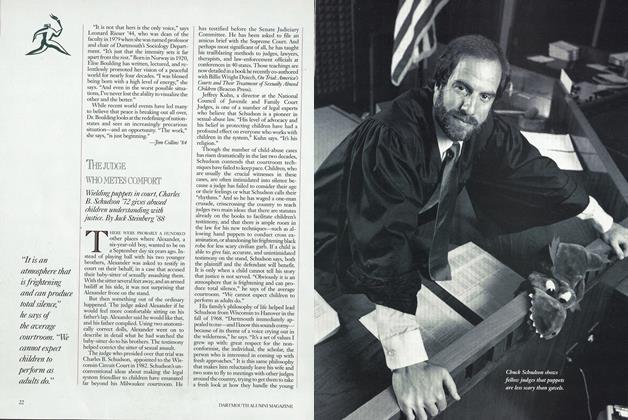

Cover StoryTHE JUDGE WHO METES COMFORT

June 1990 By Jack Steinberg ’88 -

Feature

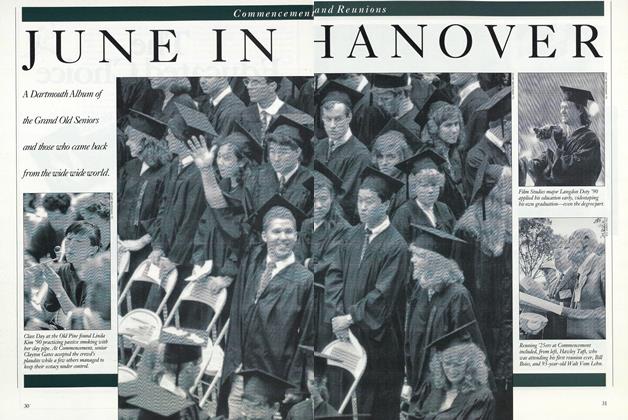

FeatureJUNE IN HANOVER

June 1990 -

Cover Story

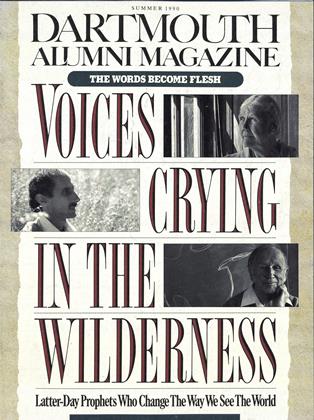

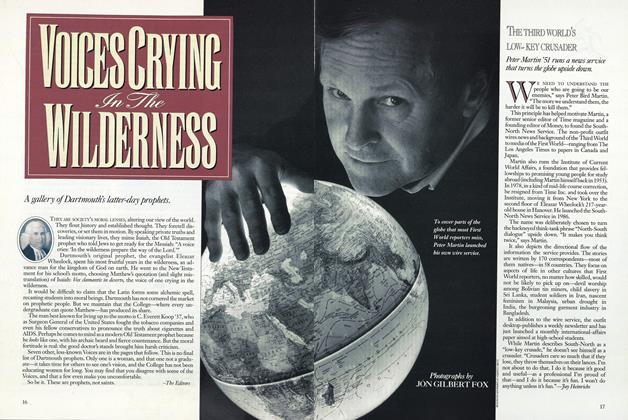

Cover StoryVoices Crying In The Wilderness

June 1990 By The Editors -

Cover Story

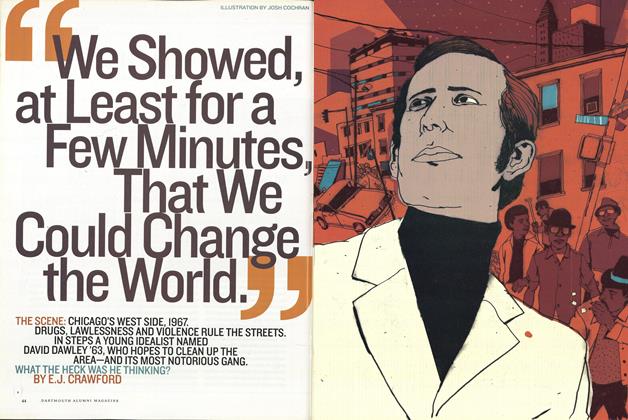

Cover StoryTHE CAMPAIGNER FOR LESS GOVERNMENT

June 1990 By Lee Michaelides

Jay Heinrichs

-

Article

ArticleProfessor William Cole: "Fifty Years From Now They'll Be Talking About This Course"

MAY • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

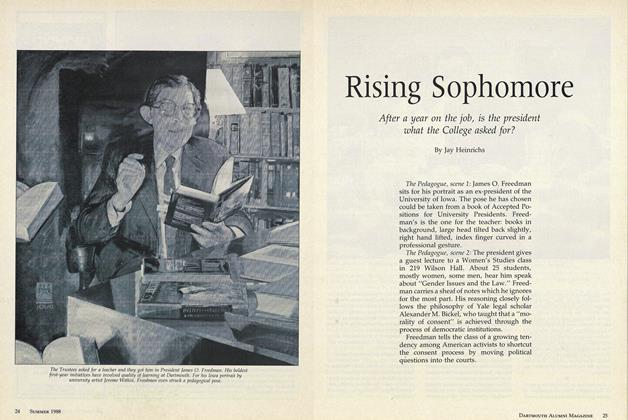

FeatureRising Sophomore

June • 1988 By Jay Heinrichs -

Feature

FeatureOn a Freshman Trip, the Destination Is Community

MARCH 1989 By Jay Heinrichs -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleNels Comes Home

April 1995 By Jay Heinrichs -

Outside

OutsideRunning With Wild Abandon

July/Aug 2002 By Jay Heinrichs