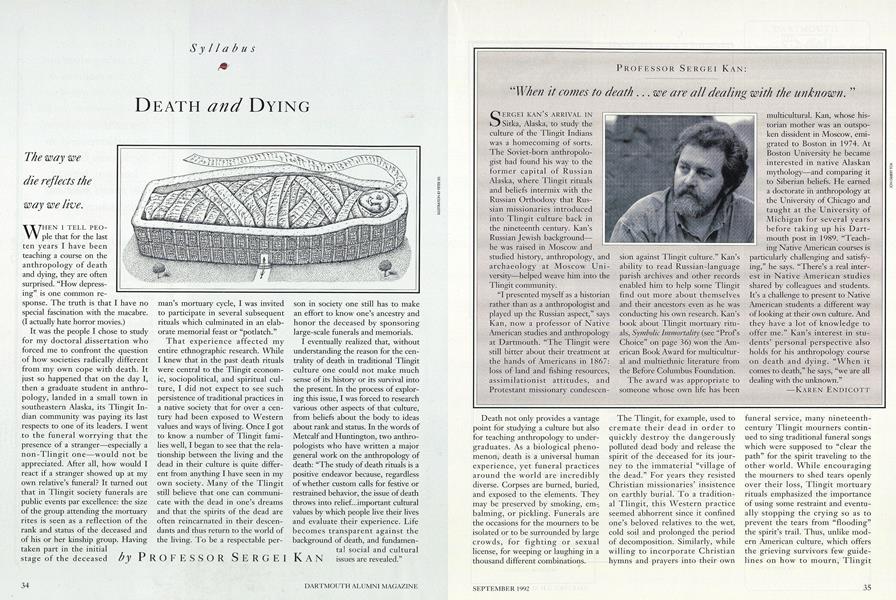

The way wedie reflects theway we live.

WHEN I TELL People that for the last ten years I have been teaching a course on the anthropology of death and dying, they are often surprised."How depressing" is one common response. The truth is that I have no special fascination with the macabre. (I actually hate horror movies.)

man's mortuary cycle,I was invited to participate in several subsequent rituals which culminated in an elaborate memorial feast or "potlatch."

That experience affected my entire ethnographic research. While I knew that in the past death rituals were central to the Tlingit economic, sociopolitical, and spiritual culture, I did not expect to see such persistence of traditional practices in a native society that for over a century had been exposed to Western values and ways of living. Once I got to know a number of Tlingit families well, I began to see that the relationship between the living and the dead in their culture is quite different from anything I have seen in my own society. Many of the Tlingit still believe that one can communicate with the dead in one's dreams and that the spirits of the dead are often reincarnated in their descendants and thus return to the world of the living. To be a respectable person son in society one still has to make an effort to know one's ancestry and honor the deceased by sponsoring large-scale funerals and memorials.

I eventually realized that, without understanding the reason for the centrality of death in traditional Tlingit culture one could not make much sense of its history or its survival into the present. In the process of exploring this issue, I was forced to research various other aspects of that culture, from beliefs about the body to ideas about rank and status. In the words of Metcalf and Huntington, two anthropologists who have written a major general work on the anthropology of death: "The study of death rituals is a positive endeavor because, regardless of whether custom calls for festive or restrained behavior, the issue of death throws into relief...important cultural values by which people live their lives and evaluate their experience. Life becomes transparent against the background of death, and fundamental social and cultural issues are revealed."

Death not only provides a vantage point for studying a culture but also for teaching anthropology to undergraduates. As a biological phenomenon, death is a universal human experience, yet funeral practices around the world are incredibly diverse. Corpses are burned, buried, and exposed to the elements. They may be preserved by smoking, embalming, or pickling. Funerals are the occasions for the mourners to be isolated or to be surrounded by large crowds, for fighting or sexual license, for weeping or laughing in a thousand different combinations.

The Tlingit, for example, used to cremate their dead in order to quickly destroy the dangerously polluted dead body and release the spirit of the deceased for its journey to the immaterial "village of the dead." For years they resisted Christian missionaries' insistence on earthly burial. To a traditional Tlingit, this Western practice seemed abhorrent since it confined one's beloved relatives to the wet, cold soil and prolonged the period of decomposition. Similarly, while willing to incorporate Christian hymns and prayers into their own funeral service, many nineteenthcentury Tlingit mourners continued to sing traditional funeral songs which were supposed to "clear the path" for the spirit traveling to the other world. While encouraging the mourners to shed tears openly over their loss, Tlingit mortuary rituals emphasized the importance of using some restraint and eventually stopping the crying so as to prevent the tears from "flooding" the spirit's trail. Thus, unlike modern American culture, which offers the grieving survivors few guidelines on how to mourn, Tlingit death rites gave (and continue to give) them a ritual framework within which the survivors could express and deal with their feelings, both individually and collectively.

This does not mean, however, that in societies where mortuary practices are complex and elaborate every person experiences loss and grief in the same fashion. As I and a number of other anthropologists have argued, an individual's response to death is determined by an interplay between his or her personality, unique life-history, and culture. Thus for some mourners a funeral might resonate with deep personal thoughts and feelings, while others may simply go through the motions. It is up to us researchers to establish the relevant factors that determine such diverse responses of the participants in the same ceremony. Hence, when lecturing or writing about death, an anthropologist is forced to deal with the most central and complex issues of the social sciences: the relationship between human biology and culture, between the universal and particular in our experience.

In the end what an anthropological analysis of death shows is that the way we die tends to reflect the way we live. Tlingit mortuary rites encapsulate their strong concern with rank and status as well as a sense of closeness and continuity between the living and the dead kin. American death ways—with an embalmed corpse "resting peacefully" in an expensive casket and a solitary gravestone with the dead person's name and dates of birth and death engraved on itmight be seen as being ordered by the values of individualism and commercialism and the optimistic orientation toward the future rather than the past that characterize our national culture. By learning about the ways "others" die, we can learn something important about ourselves. And that is, after all, one of the most important lessons anthropology can teach.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

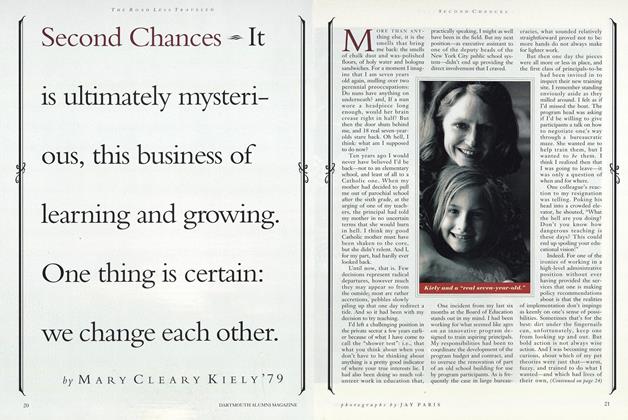

FeatureSecond Chances

September 1992 By Mary Cleary Kiely '79 -

Feature

FeatureFishing The River For A Monument

September 1992 By John Scotford '38 -

Feature

FeatureTo An Athlete, Aging

September 1992 By Mark Lange '84 -

Feature

FeatureCommunion With The High Places

September 1992 By Andrew Daniels '85 -

Cover Story

Cover StoryChoices

September 1992 By Jay Heinrichs -

Article

ArticleDr. Wheelock's Journal

September 1992 By "E. Wheelock"