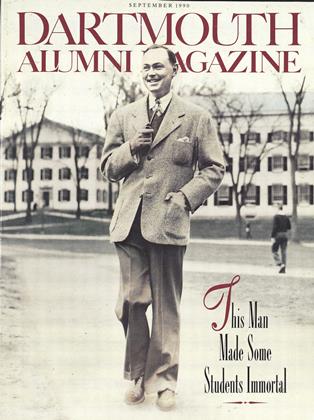

WHEN" Corey Ford became advisor to student publications in 1952, he got some advice himself on relating to kids. "Just think of yourself as a colonel," a College official counseled him, "and them as privates."

Well, Corey really was a colonel (Army Air Corps) and he already knew about relating to kids. During World War II, five-star General Hap ("The Old Man") Arnold had assigned Corey to "write about our kids. Boost their morale. Tell their stories to the folks back home." So he had flown with the B-17s over Europe and with the B-29s over Japan. He had dogged the squadron rooms and the day rooms, the hangars and the hard stands. And he wrote tales of heroism for Collier's and The Saturday Evening Post about pilots and mechanics, gunners and bombardiers, about the flying .and the fighting and the dying and, in the end, the winning.

Kids weren't privates, Corey knew. They were heroes waiting to happen.

So instead of relating to Dartmouth students from some acceptable administrative distance, Corey built bridges between faculty and fraternity, between the curricula and the extracurricula. He brought Comp Lit Professor Herb West '22 to the DKE house on a bet: challenge the kids with something relevant. So Herb talked about a popular paperback that even DKEs were reading, I, the Jury, and about Mickey Spillane, drawing inventive parallels between sex and violence in fiction and social behavior on campus, and won the bet. After that, Ernest Martin Hopkins '01 came and talked on the travails of running a school, and Paul Sample '20 on making it as an artist, and Corey coaxed John Dickey '29 into seeking DKEs' advice on how fraternities fit into the College or didn't, and so on. Corey's idea was to bust the barricades put up by authority figures so the students could see their way to the real world.

Corey was also the self-nominated, non-coaching coach of the rugby team, which the College couldn't support. For him, the team represented initiative, which was to be encouraged and rewarded. He raised money from alumni for uniforms and travel and bartered an endorsement with American Airlines for all expenses to the Monterey spring tournaments. He sold articles about the ruggers to Sports Illustrated and The Saturday Evening Post and put the earnings into the team's treasury. And when the team was invited to play in England and Ireland, he told the players, "Make your plans. I'll figure out how to get us there." And he did. The Colonel called in a chit from an air corps buddy that turned into tickets from TWA and got alumni to contribute cash and, somehow, got the U.S. Embassy in London to serve as official sponsor. It was his way of pinning medals on his players' tunics.

At Dartmouth, though, he gave so much more. He sought out students who wanted to box, and set up a gym at his home with equipment donated by Cus D'Amato, then heavyweight champion Floyd Patterson's manager and trainer.

For kids who wanted to write, Corey read their staff and worked diem through awkward sentences and paragraphs, even putting students at his own newsroom Underwood and introducing them a keystroke at a time to the mechanics of his trade. Talent was never a substitute for hard work, he'd say. You can be anybody you want to be, but you've got to work at it. Hard, he would add. He was saying what the students needed to hear and weren't hearing in the classroom.

Corey's joyous spirit boosted the morale of a corps of Dartmouth kids over the years: Dan Holland '36, Everett Wood '38, Art Zich '56, John Koehring '56, Leo McKenna '56, Joe

Mesics '54, Tom Hall '57, Pete Henderson's2, Emery Pierson '53. Joe Migely '54, this writer, and his favorites the maverick DKEs. We were his pilots and mechanics, his gunners and bombardiers, fighting the fight called growing up. And he was the Old Man who helped us. in the end, to the winning.

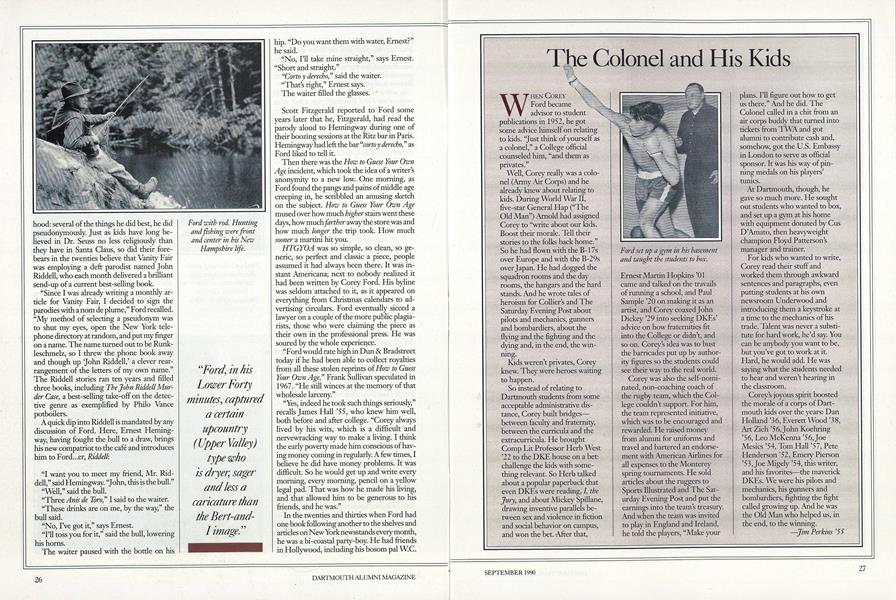

Ford set up a gym in bis basement and taught the students to box.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

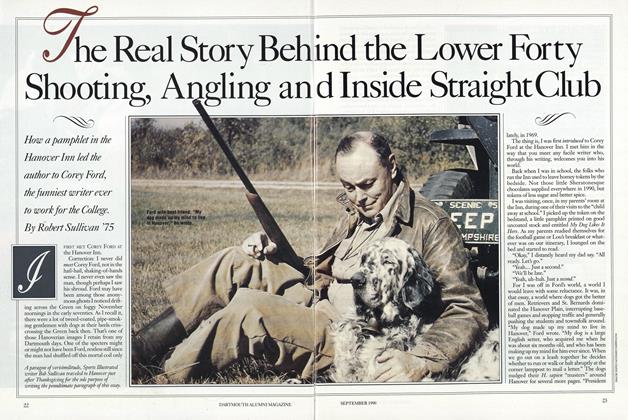

FeatureThe Real Story Behind the Lower Forty Shooting, Angling and Inside Straight Club

September 1990 By Robert Sullivan '75 -

Feature

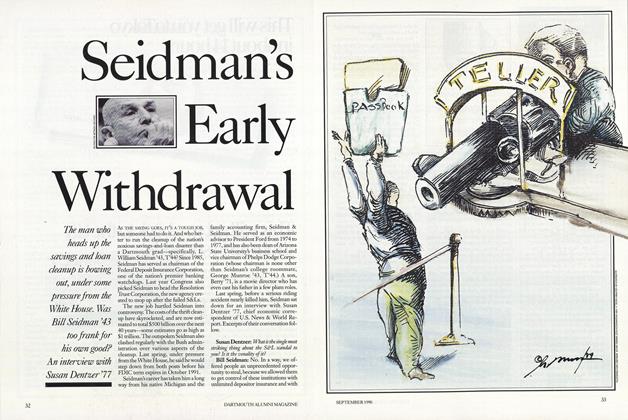

FeatureSeidman's Early Withdrawal

September 1990 By Susan Dentzer '77 -

Feature

FeaturePROBLEM SOLVER

September 1990 By John Aronsohn '90 -

Feature

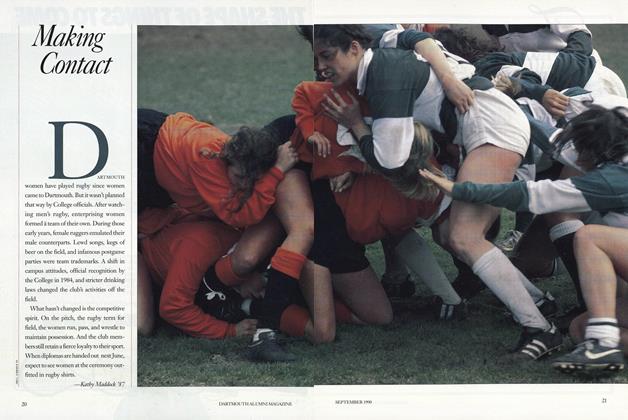

FeatureMaking Contact

September 1990 By Kathy Maddock '87 -

Article

ArticleMOTHERS AND DAUGHTERS

September 1990 By Professor Marianne Hirsch -

Article

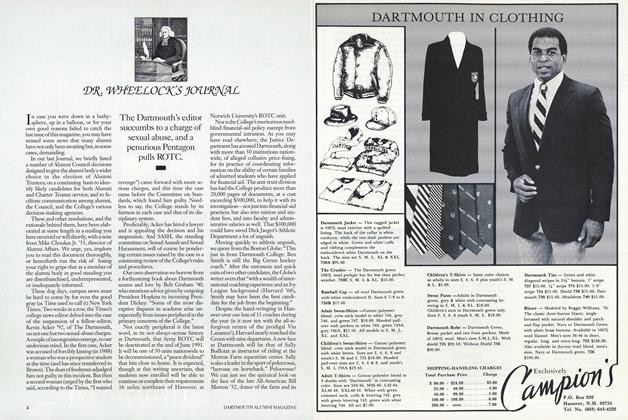

ArticleDR. WHEELOCK'S JOURNAL

September 1990

Article

-

Article

ArticlePROMINENT CITIZENS MOURN DEATH OF GENERAL STREETER

February, 1923 -

Article

ArticleYou Are Invited

OCTOBER 1966 -

Article

ArticleFootball: Six Easy Piećes

November 1975 -

Article

ArticleBull market for green grads

APRIL • 1987 -

Article

ArticleD.O.C. of Boston

January 1942 By Francis C. Ryder '50. -

Article

ArticleThayer School

June 1953 By William P. Wimball '29